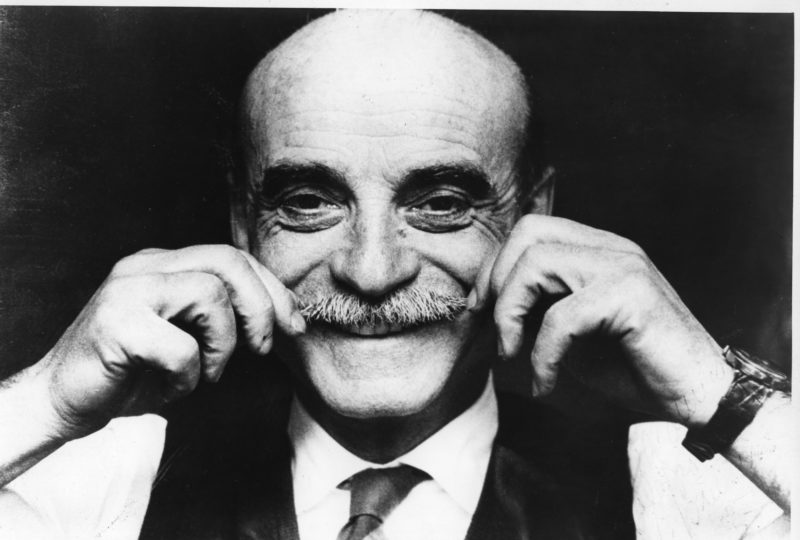

About Lucio Fontana

The Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana dedicated his entire artistic career to exploring the concepts of space, light, and void as well as the cosmos through the use of an assortment of materials such as plaster, stones, ceramics, paint, and cement.

In 1946, he founded the Altamira academy in Argentina and, along with a few students, created the White Manifesto. It states1 that “matter, color, and sound in motion are the phenomena whose simultaneous development makes up the new art.”

From there, Fontana began to formulate the theories that he was to expand to Spatialism or Spazialismo in five manifestos between 1947 and 1952. When he returned to Italy in 1947, he found his Milan studio had been bombed by Allied forces but resumed ceramics works in Albisola.

Fontana’s neon works

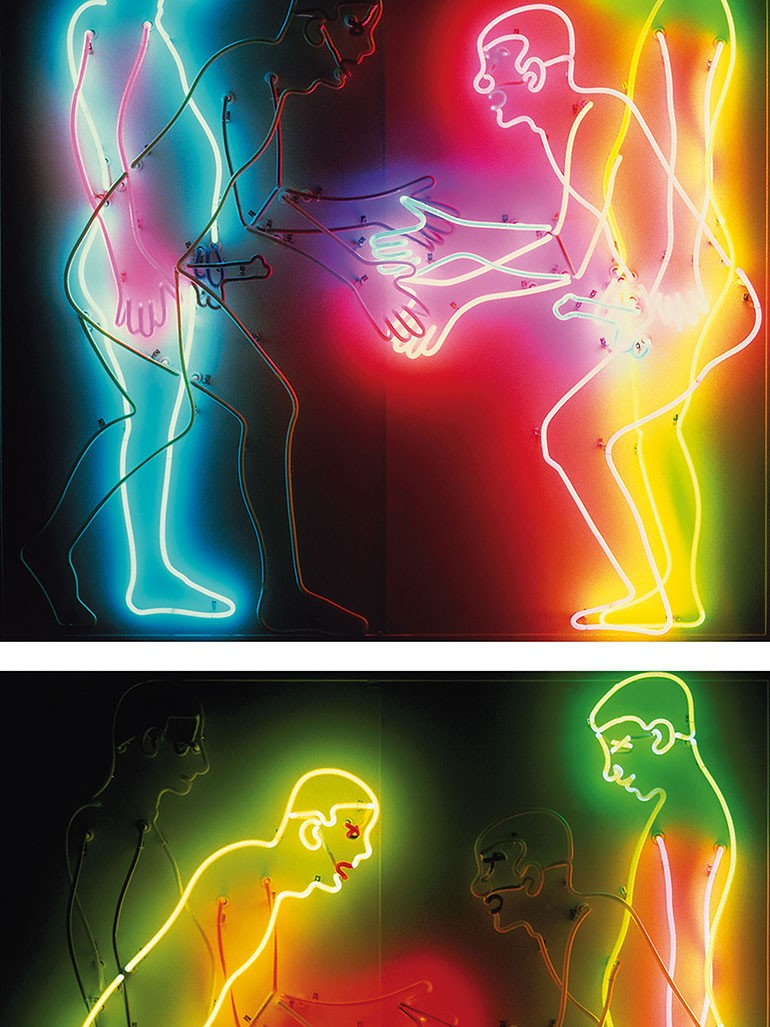

Largely inspired by technological and scientific advancements that occurred during the 20th century, he extended the boundaries of art by using cutting-edge technology such as neon and ultra-violet light and new media such as TV.

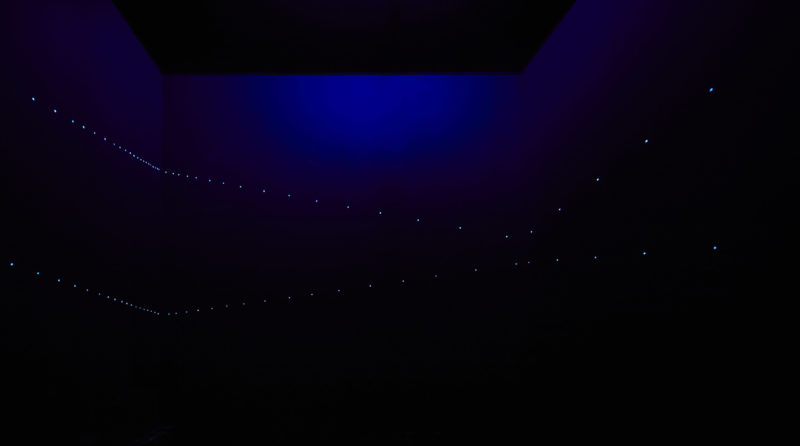

Ambiente Spaziale a Luce Nera (1948-49)

Ambiente Spaziale a Luce Nera (1948-49) was first displayed at Galleria del Naviglio in Milan in 1949. The show only lasted six days and marked a turning point in Fontana’s career and served as a source of inspiration for him for generations.

The work involves a dark room illuminated by a UV light or, as it is also known, ‘black light’. An abstract, colossal amoeba-like shape sculpture painted with fluorescent colors was hanging in the middle.

During the show, the room was completely darkened and the audience accessed the space via a black curtain. Plunged into darkness, the exhibition space was illuminated by six wood lights.

This was the first environment created by Fontana, and with it, he applied the most innovative theories he had developed in his manifestos of Spatialism from the 1940s.

It also championed a vision of art closer to the modern-day and the technical-scientific progress concerning outer space discoveries and based on an all-encompassing perception of space, conceived as the sum of time, direction, sound and light.

Speaking on the work, the artist said2:

Our intention is not to abolish the art of the past, however, nor to put a stop to life: we want the painting to emerge from its frame and sculpture from its glass case. An expression of aerial art that lasts a minute yet appears to last for a millennium into eternity. To this end, using the resources put at our disposal by modern technologies, we shall produce in the sky: artificial shapes, miraculous rainbows, luminous writings.

The artwork marked a move past the very ideal of sculpture and painting. This work promoted overcoming traditional art forms with respect to the audience’s static perception. However, it proved to be too innovative to be widely understood, and the artist even tried to repeat the experiment to no extent for a decade.

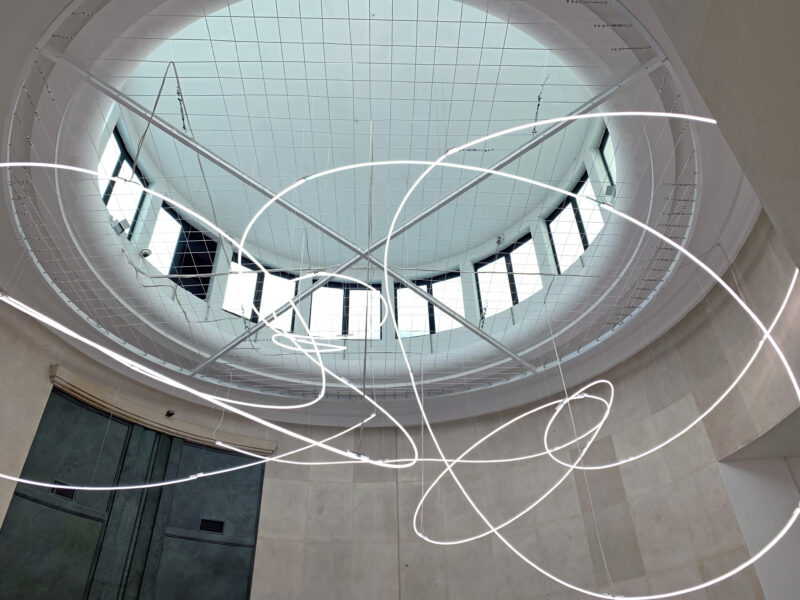

Struttura al Neon per la IX Triennale di Milano, 1951/2017

Fontana created Struttura al Neon per la IX Triennale di Milano, 1951/2017 as an ornamental component for the 9th Milan Triennale.

The vast neon was made by using up to hundred-meter-long neon tubes and was suspended by the entrance to the exhibition gallery, inviting visitors into the series of environments presented in sequential order.

Fonti di energia, soffitto di neon per Italia 61, a Torino, 1961

The work was made from seven levels of colored neon tubes. Fontana designed them for the Energy pavilion at the celebration of the centenary of the Unit of Italy in Turin in 1961.

The work foreshadowed European and American explorations of the viewing experience and the relationship between object and space.

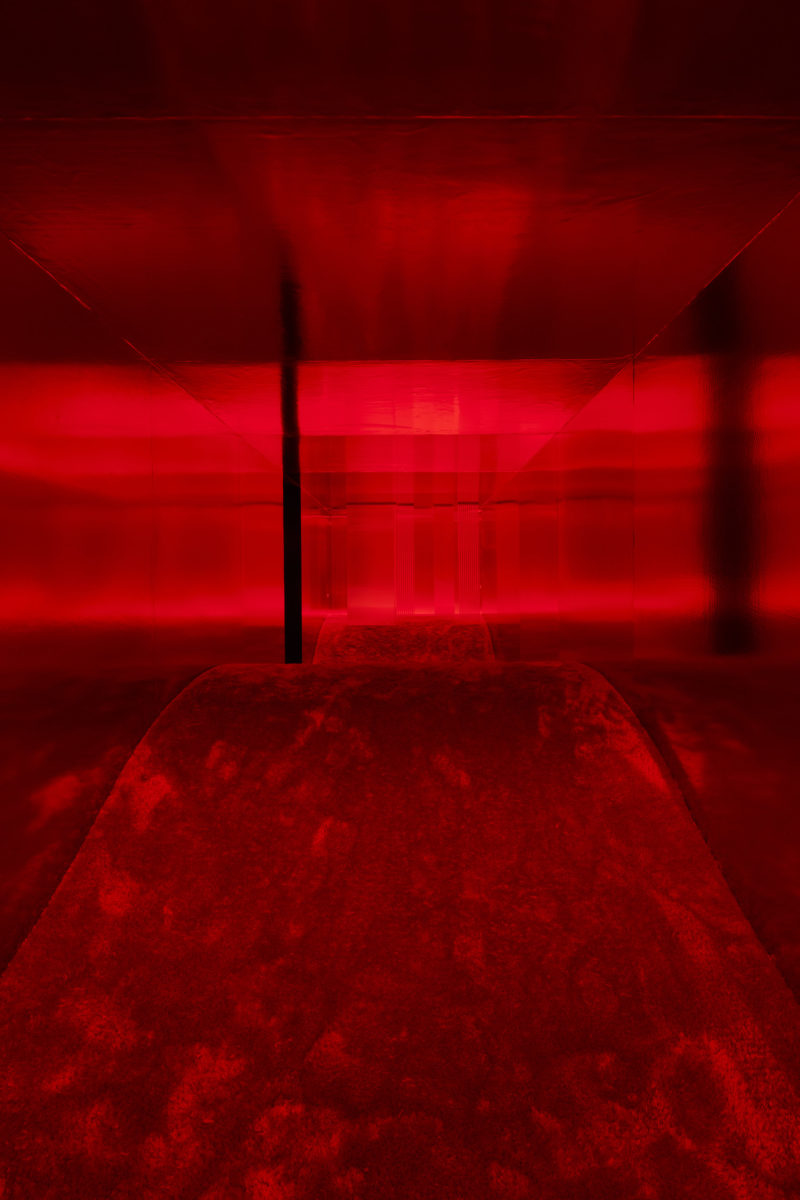

Utopie, 1966 (red)

In 1964, Fontana was among many artists invited to exhibit at the 13th edition of the Milan Triennale under the theme of “leisure”, distinguished as an expression of the transformations connected with the recent strong economic growth of Italy.

In 1964 he created two corridors, Utopie, in collaboration with architect Nanda Vigo (1936). One corridor is black and features a curved wall and green neon light that filters via a series of holes.

The other corridor was reconstructed for the first time at the HangarBicocca in 2017 and had metallic red wallpaper covering the walls and ceiling. ‘Quadrionda’, textured glass sheets were placed in the two edges of the shorter side of the environment, allowing in the light produced by the red neon tubes.

The rolling flooring was covered with a thick red carpet that created a soft, continuous space. With its playful and sensorial character, the room recalls a search for perceptive offsetting effects that can be traced back to the optical-cinematic trends of the time, to which Vigo was particularly close.

The two projects begin to foreground the perceptual experience of the audience, an aspect that the artist also focused on during the installation of his first and only large-scale solo show at the Walker Art Center in the United States.

Utopie, 1966 (black)

The second version of Utopie featured a completely black corridor with a wavy wall inside. The surface was marked by a series of holes that originated from two waving lines, which filtered in green neon lights.

Recalling the installation, Nanda Vigo said3:

So the space was all black, and by entering into this ‘tube’ you saw luminous holes that accompanied each visitor along the path, from the point of entry all the way to the exit.

Here, Fontana returned to the immersive nature of the dark space of 1949’s Ambiente Spaziale a Luce Nera, stripping it of the structural forms and experimenting with the ambiguity of perception between the movement of the sinuous surface of the wall and the sources of light.

The 1966 exhibition at the Walker Art Center in Minnesota was titled The Spatial Concept of Art. But at this time, Fontana was still in Italy and could not attend the show; therefore, the installation was done by the architect Duane Thorbeck, who was tasked with installing the work according to the artist’s specific directions.

During his exhibition in the US, the audience was required to enter and exit a central room by crouching down and feeling their way along low, pitch-dark corridors with inclined floors.

American art critic Hilton Kramer described this offputtingly negative experience4 involving the audience with the following words:

One reached this environment through a short dark tunnel, and thereupon entered a room almost but not quite totally dark. One’s feet sunk not unpleasantly into a foam rubber floor. Tiny lights, defining a regular rectangle along the floor, walls, and ceiling, created the curious illusion of a wall where, in fact, there was only empty space. Groping one’s way through this nocturnal environment, in which nothing was quite what it seemed to the eye, one exited by crouching once again through a dark tunnel to emerge in the clear light of another gallery.

Although all the black environments continue to progress on the concept of Ambiente spaziale, a luce, using darkness and optical tricks to disorient the audience, the rest of the environments use maze-like designs and colored neon to alter the space as well as a viewing experience.

Ambiente spaziale, 1967

After the Minneapolis tour, The Spatial Concept of Art went to Europe under the name Lucio Fontana, Concetti spaziali or, in English, Lucio Fontana, Spatial Concepts. The show was hosted at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1967 before traveling to the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. For this tour, the artist created three environments characterized by the use of color.

The three were titled: Ambiente spaziale (Spatial Environment), Ambiente spaziale con neon (Spatial Environment with Neon), and Ambiente spaziale a luce rossa (Spatial Environment with Red Light). They too were reconstructed for the first time at Pirelli HangarBicocca.

With Ambiente spaziale, the artist re-introduced a sculptural element from the 1949 Ambiente spaziale a luce nera, distinguished by a pop aesthetic, fluorescent paint, and reflections of black lights on the surface.

Ambient spaziale a luce rossa was structured as a red maze-like space with a series of corridors with phosphorescent colors and neon lights.

Ambient spaziale con neon features single red bent neon hanging from the ceiling in a room draped in pink fabric.

HangarBicocca exhibition

This exhibition, curated by art historian Marina Pugliese, Vicente Todoli, and art conservator Barbara Ferriani, painstakingly portrayed reconstructions of nine explorations of phenomenological and cosmic space, five of which were never seen since the artist’s death in 1968, helped the audience understand just how forward-thinking and visionary Fontana was as an artist.

A hanging arabesque, a neon structure, invited the audience into the darkened rear galleries of the cavernous Pirelli HangarBicocca, which used to be a locomotive factory. Within the unlit setting, the installation presents a series of the artist’s famous Ambienti spaziali (Spatial Environments) in independent rooms purposefully designed by Fontana.

These environments are considered the most innovative result of the theories (1947-1952) about space that the artist first expressed in his 1946 Manifesto Blanco. With this piece, the artist described a new form of visual representation associated with space and time, which would move beyond the traditional materials of sculpture and painting.

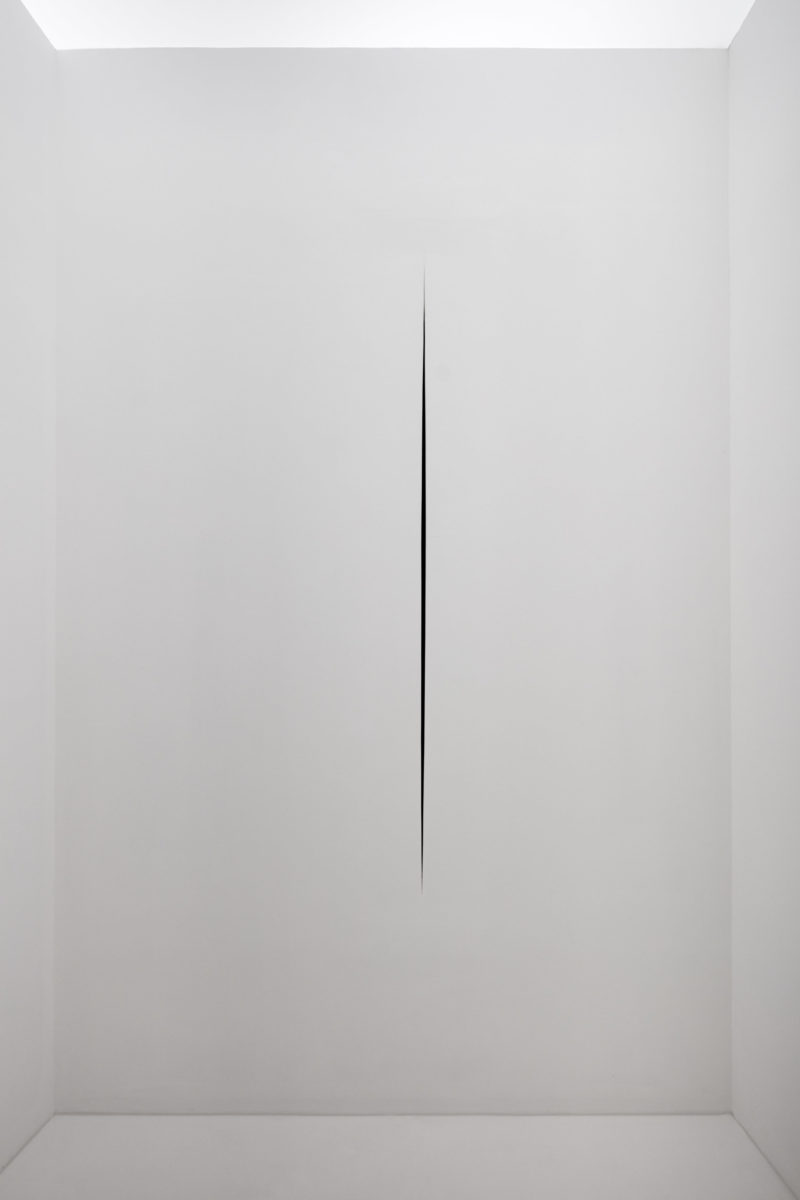

The artist, a trained sculptor, introduced the spatial element to his canvases by first puncturing them with holes in 1949 and later performing his most iconic gesture – The cut, in 1958.

Fontana’s Environments ran from 31 September, 2017, to 25 Februrary, 2018 in Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, Italy and concentrated on his pioneering contribution in the field of installation art.

Audiences and art lovers alike were excited to attend the exhibition because the displayed pieces were some of Fontana’s most experimental works, yet people know very little about them.

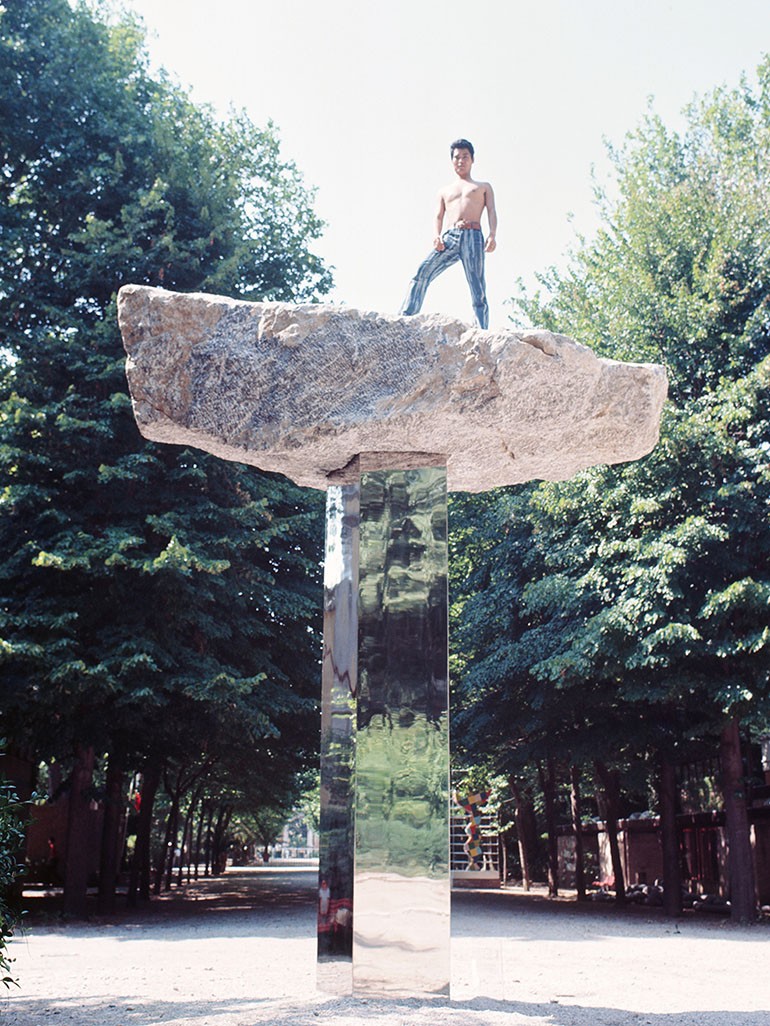

Ambiente spaziale in Documenta 4, in Kassel (1968) dates to the ear 1968, the year Fontana died.

Lucio Fontana used to destroy some of his works

Most of the spatial environments and corridors created by the artist back then were always destroyed after the show, which means that some of the environments on this year’s show have been reconstructed and assembled for the first time since the artist passed away.

To ensure that all the components were kept the same as the originals for authenticity purposes, the show’s curators sought assistance from the Fondazione Lucio Fontana.

Permanent installation in Paris

Lucio Fontana’s neon artwork for the IX Milan Triennial in 1951 is a significant piece in the history of modern art, marking a departure from traditional mediums and embracing the possibilities of technology and space. This work is often celebrated for its pioneering role in the use of neon light as an artistic medium. The piece, designed to be suspended in the air, engages directly with the surrounding space, inviting viewers to experience art as an environment.

This landmark work not only highlights Fontana’s visionary use of new materials and technologies but also represents a critical moment in the evolution of contemporary art, blurring the boundaries between art, technology, and architecture. Its permanent display at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris offers a unique opportunity to witness a pivotal experiment in the use of light and space that continues to inspire artists and designers to this day.

Legacy

Because of his groundbreaking artistic efforts, Fontana, born in Rosario, Argentina, to Italian immigrant parents, built a well-respected reputation for himself as the father of spatialism, launched in 1947, which many agree led to the immense growth of contemporary art.

It is widely accepted by students of art and professionals in the field that Fontana’s most pertinent works came much later in his career, once he had completely figured out the concept of spatialism and started producing his world-famous canvases.

As a painter, he went beyond two-dimensional surfaces by engaging technology as a means to attain expressions of the 4th dimension. By going beyond the expected, Lucio managed to create an innovative and new aesthetic dialect that blended painting, sculpture and architecture.

Fontana’s use of neon, a material then predominantly associated with advertising, recontextualized it as a medium for fine art, challenging traditional art forms and aesthetics.

After touring Europe, including London, Paris, Kassel, Zurich, and Madrid, among other locations, Fontana went back to America and also staged his work in Asia, specifically Japan.

Fontana dedicated a large portion of his career exploring various artistic concepts. His efforts and works inspired a new breed of artists and even changed how other professionals conceived sculpture, painting and space.

In the later years of his life, Fontana focused on staging his work in numerous shows that honored him around the world. He also became increasingly interested in the idea of purity achieved in his last white canvases.

Explore nearby (Pirelli HangarBicocca, Milan)

- Anselm Kiefer's teetering towersPirelli HangarBicocca, Milan, ItalyExhibition ended (dismantled in 2015)0 km away

- Elmgreen & Dragset's Short-CutMilan, ItalyInstallation ended (dismantled in 2003)7 km away

- Maurizio Cattelan's middle fingerPiazza Affari, Milan, Italy7 km away

- Carsten Höller's slidesPrada headquarters, Milan, Italy7 km away

- Martin Kippenberger's metro stationsZuoz, Switzerland133 km away