On view status

This artwork is part of the SFMoMA collection but is not currently on view. Check the official site for more details on its status and availability.

What is it?

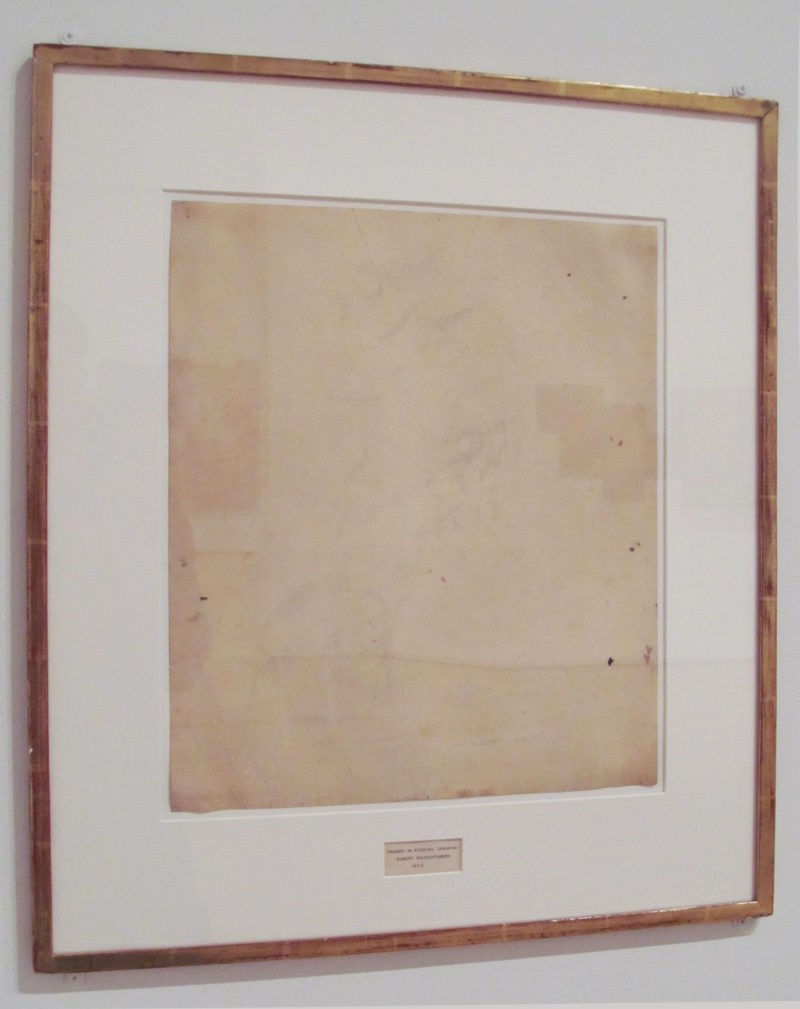

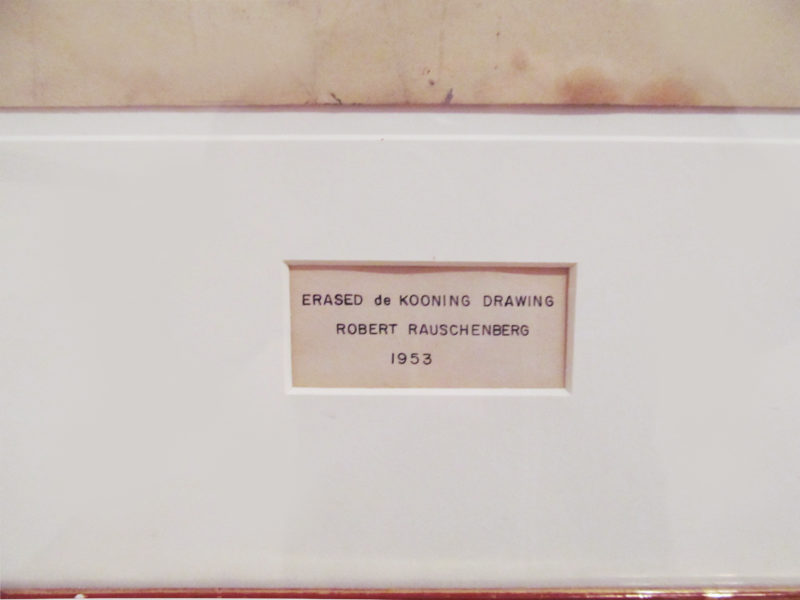

Erased de Kooning is one of the early works of the US artist Robert Rauschenberg 1. The drawing was simple: a nearly blank piece of paper in a gilded frame. The piece was developed in 1953 after the artist erased a drawing he obtained from the fellow artist Willem de Kooning 2.

Erased de Kooning is regarded as a Neo-Dadaist conceptual artwork, with close resemblance and affinities to Added Art, with material removed from the initial piece rather than added.

Rauschenberg requested his colleague Jasper Johns to include a written caption to the frame of the painting. The caption reads: Erased de Kooning Drawing, Robert Rauschenberg, 1953.

What led Rauschenberg to create this piece

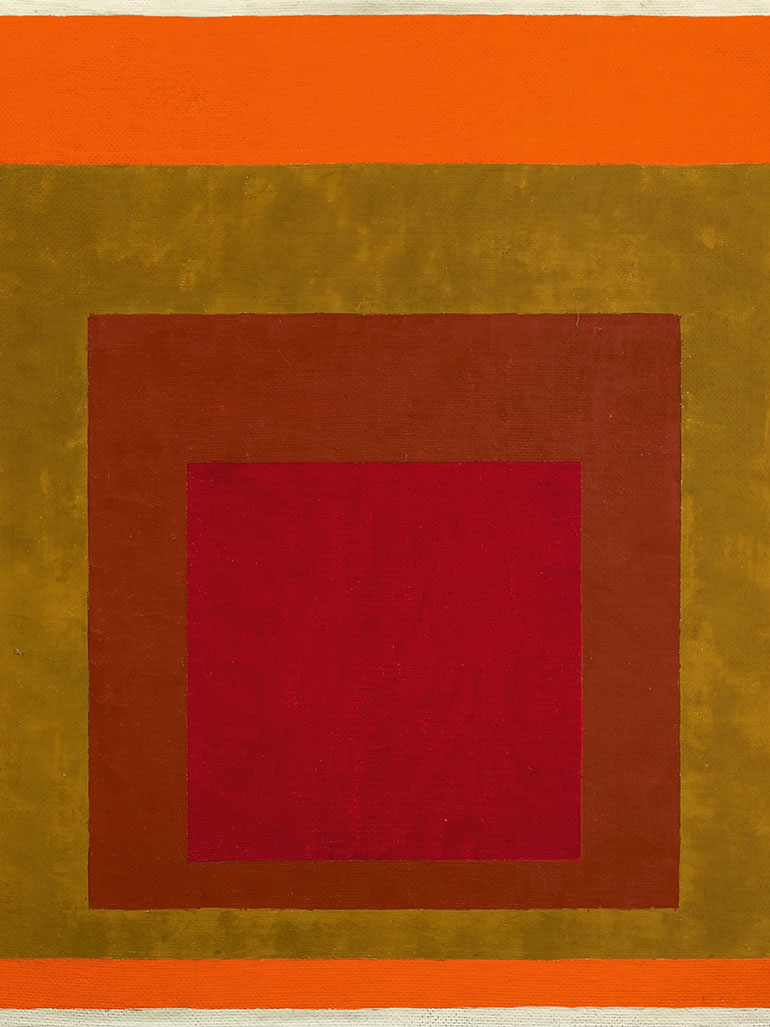

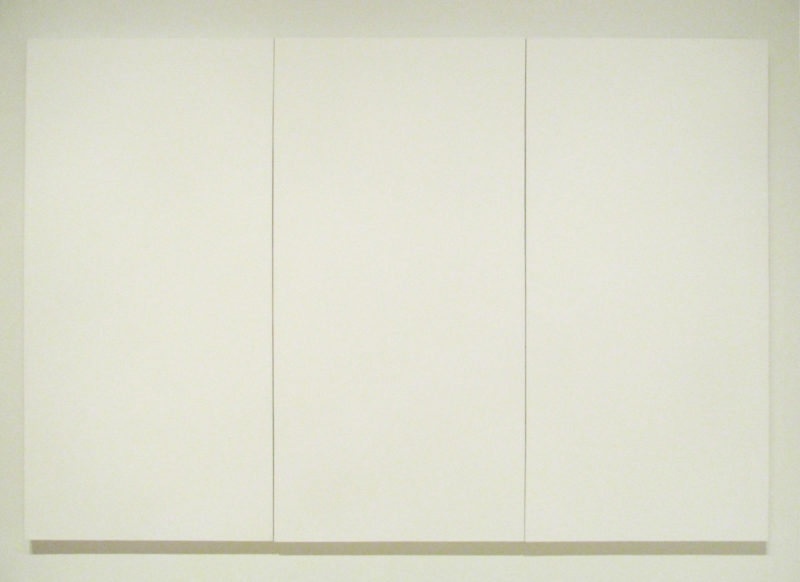

Artistically, Rauschenberg’s works combine painting with sculpture, performance, and photography. Erased de Kooning is a development from the artist’s early monochrome white drawings he first developed in the 1950s.

After a sequence of completely blank white paintings, the artist aimed to determine if a piece of art could be produced exclusively through erasure. So he began with erasing his own drawings but wasn’t impressed by the results as he thought it was not creative enough.

De Kooning’s reaction

Therefore, Rauschenberg set out to use a drawing from a more established artist. He approached one of his influencer artists Willem de Kooning and asked if he could erase his work to create a new artwork. Rauschenberg had to do a little bit of persuasion, after which de Kooning gave him a densely worked painting in pencil, crayon, ink, and charcoal, deliberately making it hard for Rauschenberg to recreate a new artwork from an original piece. De Kooning wasn’t enthused by the idea of destroying one of his paintings.

I remember that the idea of destruction kept coming into the conversation, and I kept trying to show that it wouldn’t be destroyed, although there was always the chance that if it didn’t work out, there would be a terrible waste.

The process

It took him about one month to wipe out as much of the de Kooning painting as he could, using multiple erasers. The result means the viewer has to rely on the caption and the plain gilded frame to interpret the work. Despite taking seemingly longer than expected, the artist said 56:

He really made me suffer (…) It took me two months and even then it wasn’t completely erased. I wore out a lot of erasers.

The meaning of the frame & inscription

While explaining the story of Erased de Kooning, Rauschenberg never mentions anything about the piece’s gold frame or the inscription. The two seemingly crucial elements of the painting also rarely drew more than passing mention in the early literature. When it is brought up, the artist or his chroniclers would merely state the wording and occasionally note that is it was hand-written. It is only later in his life that Rauschenberg started to relate that it was Jasper Johns, his fellow artist, who executed the inscription, something that was later confirmed by Jasper Johns himself.

In preparations for the 1991 and 1979 exhibitions, Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson researched this piece. They dated the erasure of the drawing to the fall of 1954. The duo also established that Rauschenberg and Johns met for the first time during the holiday season of 1953-1954. This chronology raised more questions than answers when the frame and inscription were added.

The artist never addressed this directly, however, but Johns says that the spur was an exhibition opportunity in later 1955. Johns suggested that Rauschenberg showed the erasure of de Kooning’s drawing, and they started to prepare the inscription. Because the two had been creating displays for department store windows as well as women’s garment distribution stores around that time, it means that they had access to a tool similar to a pantograph- a mechanical device used for duplication.

As soon as they decided on the captions’ details and arranged the letters in a metal stencil, Johns ran a stylus through the guides. An attached pen accurately replicated the captions on the adjacent sheet of the canvas. The painting was then sent to a framer to be attached with a mat that had a small gap revealing the inscription.

While there is no proof of Rauschenberg’s early attitude today, the frame, his omission of the caption, and the framing of the piece from its development story indicate that that narrative had originally crystallized for that artist before these elements attained their current significance.

After a conservation treatment in 1988, Rauschenberg directed a studio assistant to include a note on the back of the painting that reads: DO NOT REMOVE DRAWING FROM FRAME, FRAME IS PART OF THE DRAWING. This move to permanently and definitively declare both the inscription and the frame a central part of the painting. It suggests that the relationship between the two to the artwork had been raised most often than not.

Analysis

Erased de Kooning has been labeled a revolutionary of postmodernism due to its dissident appropriation of another artist’s piece. It is also considered as a rejection of the conventional drawing practice as the basis of painting. It can also be said it was a verbatim act of iconoclasm 78 – something that is so prevalent in the world of art today.

By obliterating another artist’s work, a symbolic gesture, Rauschenberg, prepared for his return to painting. His act of erasing the drawing was a way of him confronting the popularity and influence of de Kooning. While a quite strange and antagonistic tribute, it took the methods of de Kooning to such extremes that it wound up annihilating its source: an ultimate irony.

This piece can also be interpreted as a recording of an event or evidence of an action. Therefore, it can be associated with the principles of action painting or even the gestural abstraction that dominated the art scene of New York during the early 1950s.

Conclusion

Erased de Kooning is a product of its artistic period as well as a marker of an astounding moment in the artist’s life.

While the frame and inscriptions are crucial parts of the piece, it seems as if Rauschenberg did not treat them as a central or integral aspect of the work. Nevertheless, in retrospect, the artist has contributed something crucial to the art culture by obliterating the de Kooning painting.

Explore nearby

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Richard Serra’s One Ton Prop0 km away

Richard Serra’s One Ton Prop0 km away René Magritte's Personal Values0 km away

René Magritte's Personal Values0 km away

Andy Goldsworthy's Wood Line5 km away

Andy Goldsworthy's Wood Line5 km away