Parcheggio Cretto di Burri, Via Alcamo, 91024 Gibellina Vecchia TP, Italy Copy to clipboard

37.787838, 12.971495 Copy to clipboard

Before you go

Attire: Wear sturdy walking shoes to navigate the uneven terrain and bring sun protection such as hats and sunscreen. Avoid sandals.

Nearby attractions: Visit the Museo delle Trame Mediterranee in Gibellina Nuova to learn about local art and culture. The ruins of Gibellina Vecchia and the town of Salemi are also worth exploring.

Plan in advance: Check your route carefully before departure and rely on detailed maps, as navigation apps in this area often mislead drivers onto impassable roads. There is minimal signage pointing to the site, so verify directions.

Photography: The expansive concrete landscape provides dramatic photographic opportunities. Visit during early morning or late afternoon for softer lighting that enhances the visual contrast of the artwork.

Road conditions & vehicle: Use a reliable vehicle, preferably an SUV or one with good ground clearance, to handle the poorly maintained roads. Drive cautiously and stick to State Road 119 via Santa Ninfa for the safest route.

Supplies: Bring plenty of water, snacks, and any personal necessities, as there are no restrooms, cafes, or water fountains nearby.

Best visit time

Visiting during spring or autumn offers pleasant weather conditions for exploring the site.

Early mornings or late afternoons provide softer lighting, enhancing the visual experience and photography.

The site is less crowded during weekdays, allowing for a more contemplative visit.

Directions

By car

From Palermo: Drive southwest on the A29 motorway towards Mazara del Vallo. Take the Salemi exit, then follow State Road 119 via Santa Ninfa. The journey takes approximately 1.5 hours.

From Trapani: Drive southeast on the A29 motorway towards Palermo. Take the Salemi exit, then follow State Road 119 via Santa Ninfa. The journey takes approximately 1 hour.

Avoid SP5 & SP6: These provincial roads are poorly maintained and dangerous, with narrow paths, deep potholes, and potential landslides. Avoid SP5, SP6, and other similar routes suggested by navigation apps.

By public transport

From Palermo: Take a train to Salemi-Gibellina station (about 2 hours). From there, hire a taxi or arrange private transport to the site, as public buses are unavailable. Ensure your driver avoids SP5 and SP6.

From Trapani: Public transport options are very limited. Renting a car or arranging private transport is highly recommended.

Parking

Parking is available along the road near the site, but spaces are limited and on narrow shoulders.

For easier access, park near the upper entrance to avoid steep climbs. Drive cautiously when parking due to the lack of proper infrastructure.

What is it?

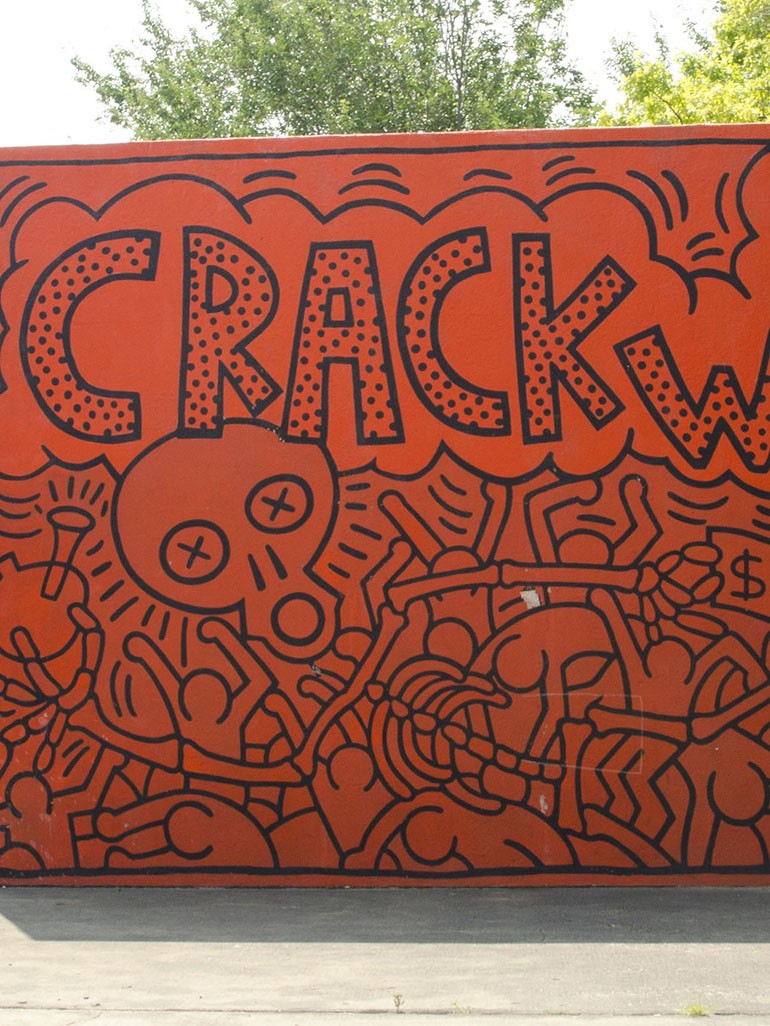

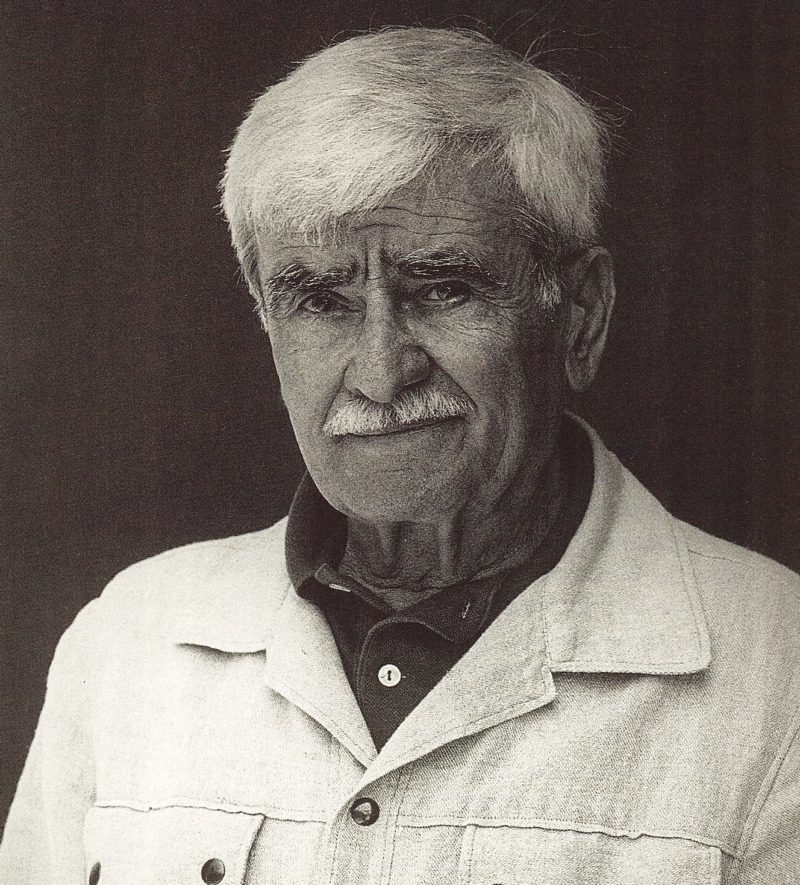

Also known as Cretto di Gibellina (crack of Gibellina) or The Great Cretto, the Cretto di Burri alias crack of Burri is a landscape artwork by Italian visual artist, painter, sculptor, and physician Alberto Burri 1.

He started to work on it in 1984 and left it unfinished in 1989 because of a lack of funds. It finally got finished in 2015 and is located in the rather remote 2 small city of Gibellina in Sicily 3, Italy 4.

Background

The history of this land art 5 sculpture 6 coincides with the destruction of the city of Gibellina by the 1968 Belice earthquake 78. A powerful quake completely flattened the city, leaving thousands of families homeless. The desire for the renovation of the town was harbored by then-city mayor Ludovico Corrao.

After the earthquake, the town’s reconstruction at its previous sort was unfeasible and temporary prefab houses were erected below the city to accommodate its population of 6000. It was later decided that a new town be constructed in Salinella, around 20 kilometers west of the old city, that already had train and road access.

Carrao welcomed the opportunity to create a new modern city that would become a centerpiece of modernity and saw art as a social redemption of the city; Alberto Burri was one of the artists to offer solutions.

In 10 years, the city was constructed with wide roads, single double-story houses, many squares, an administrative center, a cultural center, and a Modern Art Museum. The new museum, which was envied by larger cities, was filled with paintings of contemporary Italian artists. The city council decided to invite Alberto Burri and other artists to add to their contribution to the new city of Gibellina.

The merit and significance of your artistic message is considered to be humane and poetically inspiring [and] more than any other, it is able to translate for the present generation and for future generations the tragedy, the struggle, the hope and the faith in the land of the people of Gibellina.

Joseph Beuys 11 was also invited to Gibellina and visited in 1981, but only left photographs of his visit, which are now displayed at the town’s museum and enlarged into large posters.

Initially, Burri had ignored the invitation, but the mayor persisted and even paid him a personal visit. After touring the city, the artist decided against adding another piece of art to an already saturated field. But when he toured the remains of the ruins of the old town, which had not been touched since the earthquake, he came up with the idea of the Cretto di Burri, a land artwork that would preserve the entire site of the derelict city of Gibellina.

Speaking on how he got involved, Burri said 1213:

When I went to visit the place, in Sicily, the new town was almost completed and was full of works. I’m not doing anything for sure here, I said right away, let’s go and see where the old town once stood. It was nearly twenty kilometers away. I was really impressed. I almost felt like crying and immediately the idea came to me: here, here I feel that I could do something. I would do this: we compact the rubble that is so much a problem for everyone, we arm it well, and with the concrete, we make an immense white crack, so that it remains a perennial memory of this event.

The artwork

To help restore the city back to it its former self, Burri designed a massive monument that retraced the streets and alleys. He used blocks made by accumulating and caging the rubble of the old structures.

The massive yet walkable slits in the concrete mimic the old Gibellina, re-conjuring three-dimensional memories of the destroyed city while simultaneously marking its status as dilapidated ruins.

Viewing from above, the monument looks like a series of concrete fractures on the ground, whose artistic quality lies in the freezing of the historical memory of a country.

Having lived in Los Angeles and frequently visiting Death Valley, Burri became deeply interested in the case of natural cracking in the land, resulting in him to begin incorporating cretti (cracks) in his works in the early 1970s.

Each crack measures two to three meters wide, while the blocks are 1.6 meters high and spread around 80,000 square meters, making it one of the largest contemporary artworks in the world.

The meaning

In Burri’s opinion, the cracked landscapes of Death Valley that had influenced his work served as a psycho-geography, signifying the violence and trauma of fascist rule as well as industrialized warfare that he witnessed as an Italian citizen living through both World Wars.

Similarly, the cracked white concrete of this monument memorializes and conceptualizes the ordeal and suffering of the Belice earthquake, with the slits marking not just the literal streets and corridors of the old town but also the violence done to the land, people, as well as profoundly to the cultural memory of the site.

The white concrete used in the construction of the monument signifies the pale corpse of the lost city, while the slits and textures marking the presence and memory of the old town expose the futility of erasing and moving forward on a psycho-geographic tabula rasa.

Process

The residents were not welcoming of the idea of a giant concrete monument on the site of their old city. To convince them, Burri created a model of a large version of one of his crack paintings but made of concrete, with the fissures representing the original street map of the old city.

After plenty of discussions, the residents agreed. Crews assembled the ruins, including the cars, the clothing, the books, the toys, and anything else left behind – and buried them within the concrete version of the Cretto, thus preserving it in a mausoleum.

Burri termed this “the archaeology of the future 1415“, a symbol that a cultured society continued on this location even after a tragedy. Mayor Corrao, on the other hand, called on the residents “to obliterate the ruins in order to commemorate them,” an implicit acknowledgment of the technique Burri used to develop his crack paintings, as well as a call for creative destruction as the cracks only emerge as the surface slowly decay over time.

Burri followed the lines of the old streets and corridors by containing the debris, which featured stones, rubble, domestic remnants, and furniture 16 in gabions. He used the military and employed the services of the construction companies building the new town.

Cement was poured into the mold of the urban footprint, creating an abstract pattern of white concrete blocks echoing the shapes of the buildings, with fissures following the old streets and roads.

Completion after 30 years in the making

The monument sits on an 8,000 square meters landscape. In 1989, the project ran out of funds and the work was halted when around 6,000 square meters of space had been covered. Nearly a decade later, a petition was lodged by art historians and other prominent Sicilians calling for the completion of the project, and funds were raised to complete the last nine acres.

The concrete, which has now turned grey, hints at a Columbarium in the style of an Italian cemetery where ashes and remains are placed in miniature houses or wall compartments.

In 2015, Cretto di Burri was finally opened to the public after thirty years in the making. The completion of the project coincided with Burri’s 100th anniversary and the time when the artist’s market was experiencing a massive resurgence. The project’s inauguration was also accompanied by a string of solo exhibitions across cities such as New York 17, London 18, and Luxembourg.

In 2015, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum commissioned Dutch filmmaker and photographer Petra Noordkamp to create a 15-minute film 1920 about the Cretto. She visited the site several times to create a film which was reviewed by the New York Times 2122:

This usually poignant work of land art is represented here by a film by Petra Noordkamp that ends the show on a high note. Burri’s cracks are, in this case, pathways for visitors, evoking both a ghostly street plan and an earthquake’s riveting power.

Inspiration

Born in Umbria, Italy, in 1915, Burri grew up in a region so rich in art history that he did not have to study art in school. He earned his medical degree from the Perugia University and in 1940, he was conscripted into the Italian army for World War II. After serving two and a half years, he was captured as a prisoner of war and sent to Hereford, Texas, United States.

It was there that he began to paint, and after returning to Italy in 1946, he began cultivating a personal aesthetic style seemingly inspired by his time in the war. Using basic materials such as sackcloth, tar, pumice, and sand, as well as employing techniques such as ripping, sewing, and burning, Burri created artwork that resembled bandages, scored earth, blood, and decaying flesh.

Residing somewhere between sculpture, painting, and relief, his strange works contain an emotional presence that triggers visceral reactions from the audience.

He spoke very little about the work, although he suggested that as time went on, his techniques became less about the terrors of war and more about his allure of the expressive power of materials and processes. The turning point for his work was when he visited Los Angeles in early 1960 for a holiday.

During his stay, Burri toured Death Valley and experienced how the sun scorched the parched earth to form massive fissures in the dry ground. These fissures reminded him of those he had seen on flesh during war times and surfaces of old paintings. The experience in Death Valley inspired him to commence a series of works titled cretto or cracks.

The idea came from there [Death Valley], but then in the painting, it became something else. I only wanted to demonstrate the energy of the surface.

Burri had invented chemical concoctions that he could spread across a surface in variable amounts, guaranteeing the solution to crack as it dried. With this chemical, he could decide how deep the cracks would go by just changing how much he spread on the surface.

It also helped him predict where the crack would form. His process, however, just like with any other human interaction with nature, was a mixture of control and accident.

Critics have likened Burri’s creation to Lucio Fontana’s 25 Cut Paintings, which his fellow countryman started creating in 1959. In 1974, Gordon Matta-Clark 26 famously split a house into two pieces 2728.

In turn, Alberto Burri has influenced generations of artists to come. In 2007, Doris Salcedo 29 created her well-known crack installation Shibboleth 3031 in Tate Modern.

Traces of Beuys

Joseph Beuys traveled to Gibellina, where he met with Alberto Burri. Beuys was already a prominent artistic figure not only in Italy but in the world. The trigger for that chance meeting and its promotion was that Beuys and Alberto Burri shared a common path in the past. They both studied medicine, served their countries during the war. Both also served time as war prisoners, and both chose art as their secondary career.

Although they both used unusual materials in their work, in their art and personalities, they were a world apart. For Beuys, the stage and his personas were central to his artwork. Burri, on the other hand, avoided the limelight as much as possible.

Final words

Cretto di Burri is a memorial to a calamity and thus, it is an artwork with an emotional link to its location. The monument is surrounded by ruins and clumps of upturned grounds, which function as witnesses to the massive power of destruction.

The peacefulness that the artist wanted for this location is there, as it nuzzles silently amidst green thickets and cypresses and possesses the atmosphere of sacred grounds. As an abstract form of a memorial without any symbol, Cretto di Burri manages to successfully recreate the feeling of the existence of an enormous force.