Who is Nick Cave?

Nick Cave 1 is an American fabric sculptor, performance artist, and dancer. He was born on February 4, 1959, in Fulton, Missouri. Currently, Cave lives in Chicago, Illinois, where he works at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as the director of the graduate fashion program.

Nick Cave’s work is inspired by African art traditions, ceremonial dresses, armor, designed textiles, haute-couture fashion, and stereotypical feminine items.

Biography

His large family inspired him to become an artist and the attentiveness required in the field. His journey began when he used to manipulate fabrics from hand-me-downs from his older siblings. After high school, Cave joined the Kansas City Art Institute, where he graduated in 1982 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts. After graduating, Nick Cave ventured into dancing and got his training from Alvin Ailey.

Soundsuits

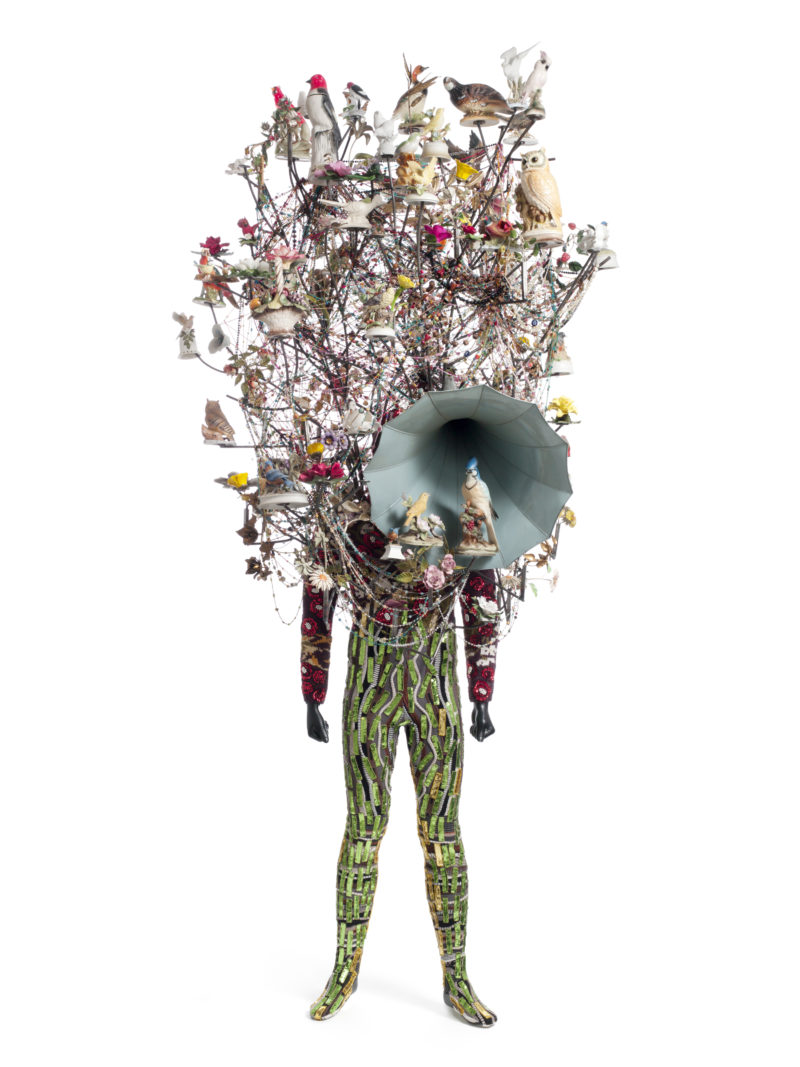

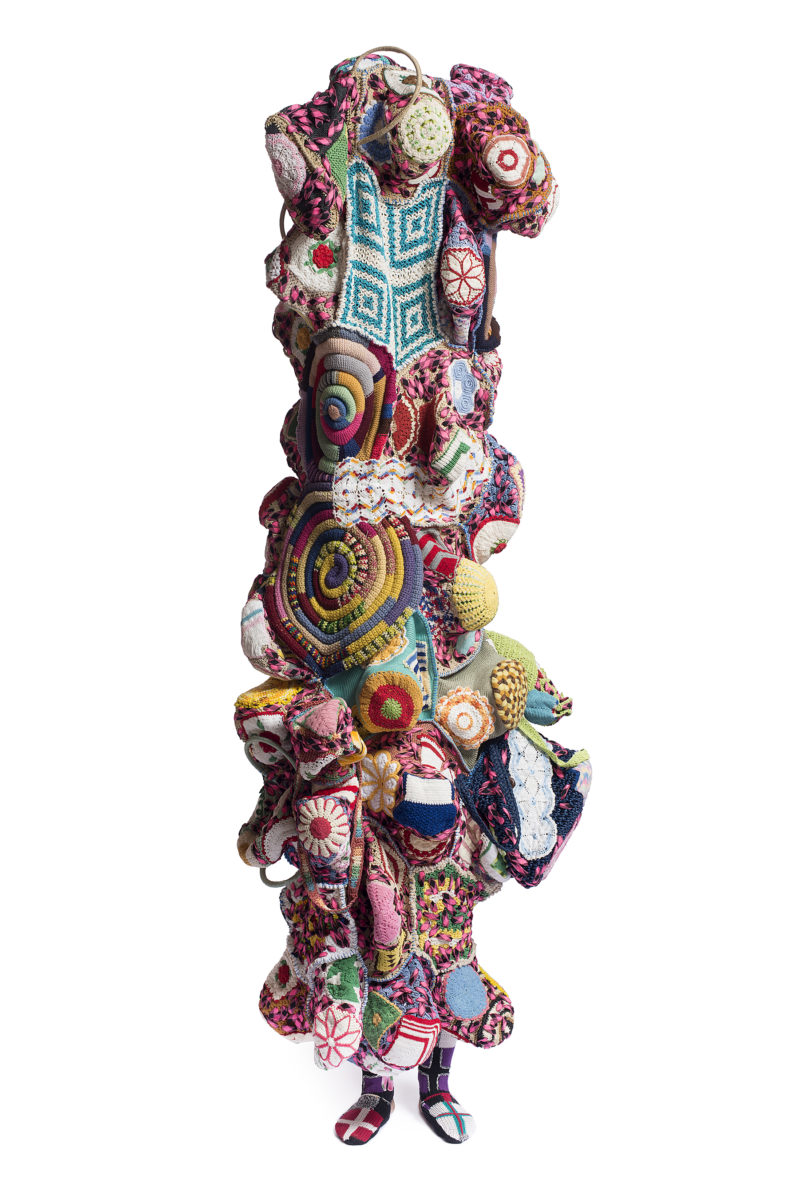

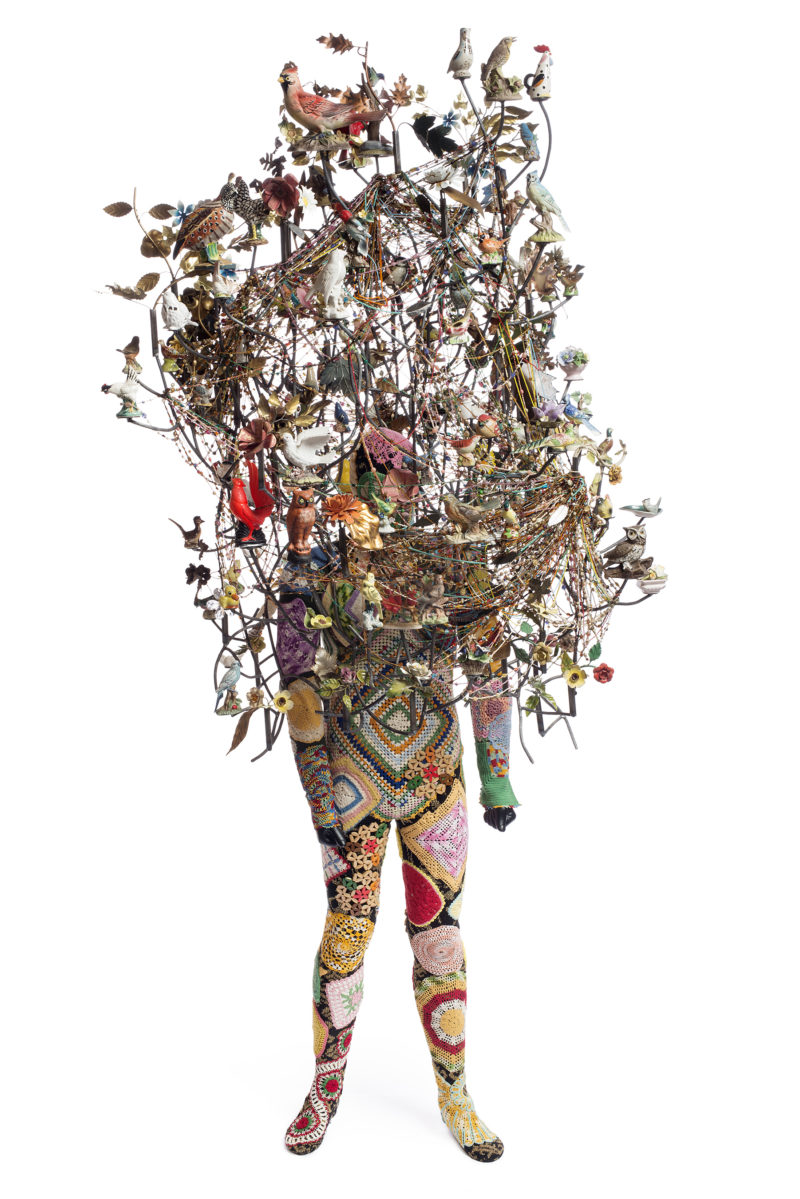

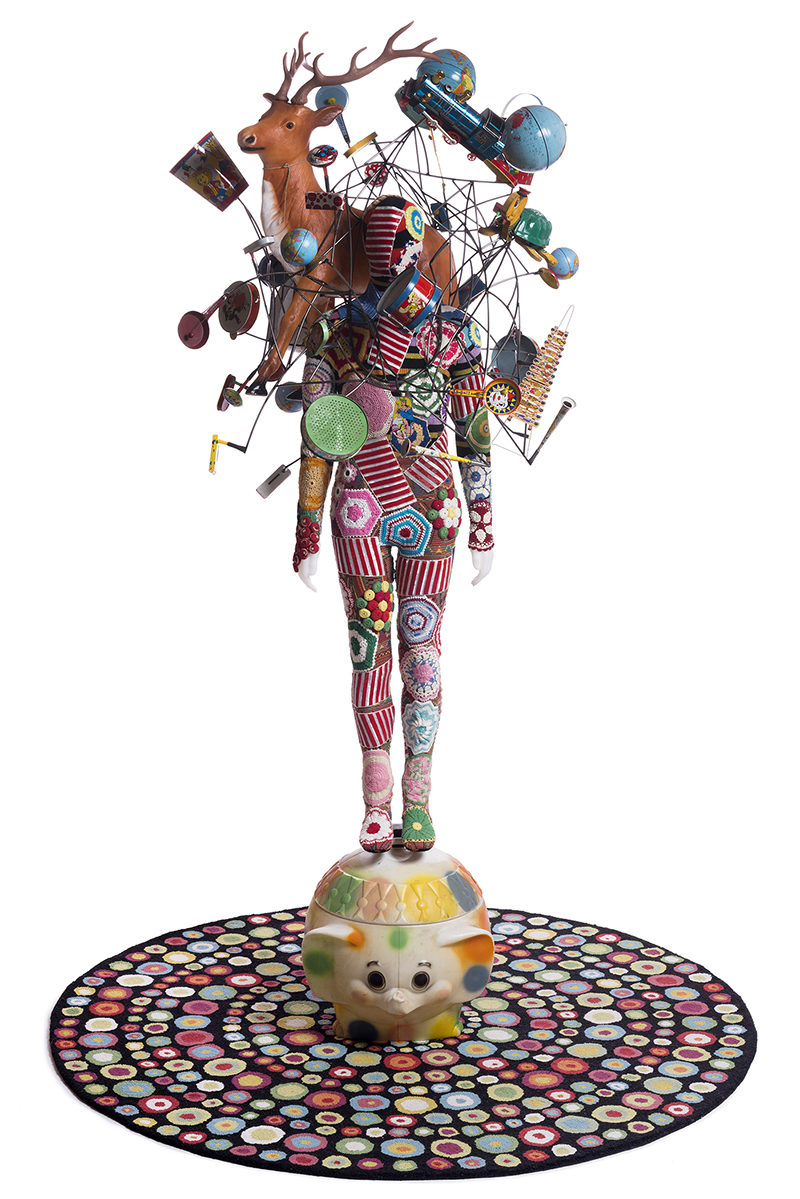

Nick Cave’s best-known work is the Soundsuits series, costumes that completely cover the individual’s body. They camouflage the wearer’s shape, enveloping and creating a second skin that hides gender, race, and class, thus compelling the audience to watch without judgment.

The artist usually makes the Soundsuits from sisal, dyed human hair, beads, plastic buttons, wire, feathers, and sequins. He uses these everyday objects to construct an atmosphere of familiarity with the rearrangement of the items into understandable representations of both material and social culture. The pillars of his work are mostly race, gender, and identity.

To date, Cave has created over 500 Soundsuits since the first creation in 1992. Cave draws inspirations from choreography and dance, which blends perfectly with Soundsuits as they enable the expression of both one-piece and art.

Origins

The artist owes his upbringing to the development of his artistic techniques and skills. Growing up, he was forced by his older siblings to repair hand-me-downs, not knowing how the experience was shaping his future career as an artist.

He quickly learned and developed his skills in fabric manipulation. Cave’s first Soundsuit was made from what he had learned from manipulating fabrics.

The first Soundsuit & Rodney King

Cave released his first Soundsuit in 1992, a “demonstration” against the brutal beating of Rodney King. Cave recalls 23:

It was a very hard year for me because of everything that came out of the Rodney beating. I started thinking about myself more and more as a black man – as someone who was discarded, devalued, viewed as less than.

I started thinking about the role of identity, being racially profiled, feeling devalued, less than, dismissed. And then I happened to be in the park this one particular day and looked down at the ground, and there was a twig. And I just thought, well, that’s discarded, and it’s sort of insignificant. And so I just started then gathering the twigs, and before I knew it, I was, had built a sculpture.

He used sticks and twigs collected from the ground and crafted them into an outfit that made sounds when worn. Cave pierced tiny holes at the base of each part and joined the twigs together with a wire. And just like that, the first Soundsuit sculpture was created.

Nick Cave said about the first sculpture 45:

I was inside a suit. You couldn’t tell if I was a woman or man; if I was black, red, green or orange; from Haiti or South Africa. I was no longer Nick. I was a shaman of sorts.

How he selects the material

Inspired by the newfound sense of freedom, Cave set off on a journey that he never knew would reach this far. He began to work on more outrageous and fabulous sculptures from simple materials he found in thrift shops, flea markets, and across the country.

The artist admits that he usually doesn’t know what he is looking for when creating the sound suit or how he will put it in use once found. But when he discovers the most suitable materials, he usually spends a considerable amount of time identifying the best part of the body the found material can sit. When this is resolved, he gradually starts developing the Soundsuit from this point.

Commenting on his exhibition at The Anderson Collection at Stanford University in 2016 and 2017 67, Nick Cave said:

I never think anything is finished. But I do know when a piece has life, when it has a pulse, when it’s breathing…Then I can walk away because I know it can sustain itself in the world.

Performances

Often, the Soundsuits are presented to the audience as static sculptures. However, they can also be viewed through live performance, photography, and video, which are also some of Nick Cave’s skills. Cave himself devises the performances.

To bring his static sculptures into life, Nick Cave would sometimes perform in the costumes himself. He dances before the camera or live audience, triggering their full strength as musical instruments, a living icon, and attire.

Nick Cave wants Soundsuits to be seen without asking about the artist behind the creations. Wearing the suits, you don’t know the person inside. You don’t know their gender, age, race, or any fact about their identity.

Heard performed at the University of North Texas, 2012

Heard performed at Grand Central, New York, 2013

In 2009, the audience got to see the Soundsuits sculptures come to life at the Grand Central Terminal’s Vanderbilt Hall in New York. Nick collaborated with dancers from Alvin Ailey Dance Company, where he used to work as a dancer, and created HEARD.NY. The event didn’t fail to impress. The audience witnessed 30 performers in gigantic horse costumes stomp, twirl, and shake their tails.

References

Nick Cave’s creations strike a sharp resemblance to the performance costumes of Leigh Bowery in the 1980s and early 1990s. Both outfits are inspired by traditional practices (macramé, needlework, and crochet), which are wearable works of art.

Analysis

Soundsuits can be best described as a blend of color, noise, and texture. They are artworks that can be worn or be displayed as motionless objects or fused into a wild performance as costumes. Soundsuits conveys the real-life risks of vulnerability and consequences by changing the experience and environment.

The Soundsuits lash at something that not many other artists have ever tried to confront. They confront discrimination of all kinds. Alongside the discrimination against color, age, and gender, Soundsuits also faces discrimination against the preconceived notions that art should not be interactive.

When one performs inside the suit, they are allowed to move with less inhibition. Concealing a performer’s identity is invigorating, especially when one considers the frequency of the society making sudden judgments about a person’s inferiority based on visual signals.

The meaning

The Soundsuits are still open to different interpretations and associations. For example, Kate Eilertsen, a former curator at Yerba Buena, associated the Soundsuits sculptures as “traditional crafts forms like macramé and crocheting.” On the other hand, Dan Cameron, the New York curator, writing in an essay states 89:

I think he has picked up the threads of these – I wouldn’t say outlaw but slightly marginalized – traditions and pulled them into the front and center of museum culture.

He also admired how the artist links “static objects in museum space with human movement.

Soundsuits can propagate several concepts at once, and their interpretation can vary depending on their environment, fixed state, movement, and or the addition of group choreography. The finished items resemble the African ceremonial masks and costumes, as well as carnival costumes, Rococo, Dogon costumes, and ball culture.

The suits look shiny and abnormal, but that should prevent the underlying message from being received by the audience. Nick Cave states that Soundsuits represents his urge to “lash out” in response to sorrowful moments in the history of the United States or personal experiences.

In his interview with Art21 1011, Nick Cave said this:

And if I do, lashing out for me is creating this. The Soundsuits hide class, gender, race, and they force you to look at the work without judgment.

Exhibitions

In 2016, Cave worked on his massive exhibition for MASS MoCA titled “Until 1213“. The audiences seem to appreciate the work of Cave. Since the first costume was created, Soundsuits has grown slowly and steadily and has since hit a tipping point.

Another indication of how wider the audience of Soundsuits is can be seen in the fact that one of the sculptures from the series has been included in the Brooklyn Museum’s recently opened show “Disguise: Masks and Global African Art.

On June 7, 2018, Cave converted the expansive Drill Hall at the Park Avenue Armory into an auditorium for his two exciting projects. He mixed the elements of installation art, performance, rave-party bacchanalia, and playground glee and created an ecstatic event.

At the Denver Art Museum, an exhibition of Soundsuits spans different rooms.

Popularity & Market success

Speaking in an interview, Cave’s primary dealer Jack Shainman had this to say 1415:

There is not a day that people aren’t calling about his work or museums interested in putting on shows. I think it’s what’s called a ‘luxury problem,’ but we’ve been having to turn down museum shows.

Recently, the Seattle Museum of Art acquired different Soundsuits. So far, Cave’s works have appeared in auction merely 16 times, nine of which are Soundsuits according to the Artnet data. The highest price for a Soundsuit in an auction was $150,000 in 2008 by Sotheby’s.

Sotheby’s head of contemporary art day sale and the associate vice president was recorded as talking about the rising popularity 1617:

In the past few years, as they come to market, more and more people recognize that not only are they incredibly beautiful sculptural works that have a performative history, but they are also an investigation into each of the stories for the impetus for their creation.

Cave affirmed that the demand and appeal of Soundsuits are not limited to a specific material or style, though according to Shainman 1819, “people love the button Soundsuits”.

Art or objects?

Despite the Soundsuits being around for many decades, many people still don’t know if they should qualify as body sculpture, art, or fashion. But that shouldn’t come as a surprise. In the Western philosophical tradition, there is no clear definition of what registers as aesthetically beautiful.

In Western culture, art objects are supposed to be valued based on their formalistic detail, wholly detached from any historical or social interpretation, and distancing the observer from the observed.

This classification of what compounds as aesthetic excludes any art projects that require interaction between the object and the audience. The audience is urged to “focus on the object rather than on social and economic considerations” about the object.

The interaction through interpretation is not encouraged. Works that support physical manipulation of the viewer, rather than just being viewed, are typically excluded from all definitions of high-art.

Going by this definition, art is supposed to be untouched, and if it crosses the boundaries and becomes a “touchable” object, it qualifies as a tool and not an art.

Final words

Cave’s Soundsuits are unique art pieces, combining art, fashion, and performance, created by an “artist with a conscience,” a trailblazer for mixing art, participatory performance, and craft. Behind the whimsical, wearable sculptures, Cave had a message or wanted to lash out at something.

The series goes against the Western definitions of aesthetic prestige that dismiss other types of artistic mediums. The artists use less valuable objects to challenge the rigid philosophies of what constitutes high art and what it does not.

However, the primary aim of the Soundsuits is to use art to confront any form of discrimination. They also allow the audiences to notice the art and not the social worth of the person inside the suit.