Introduction

Guernica is one of Pablo Picasso’s 1 most famous works. This mural-sized oil painting on canvas was done in 1937. He used a palette of gray, white, and black colors to bring out a political statement denouncing the unnecessary sufferings brought about by bombings caused by the German Fascist regime. The nearly 3.5 meters tall by 7.77 meters wide mural depicts people whose lives have been wrenched by chaos and violence. Part of the mural is a burning horse and a bull that has been gored.

Many within the art world consider it as one of the most moving and influential anti-war paintings ever. The piece is currently exhibited at the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, Spain. The most dominant figures in the painting are a bull, a wounded horse, mutilation, screaming women, and flames.

Why is Guernica so famous?

The inspiration to create the painting came after the town of Guernica in Basque county located in northern Spain was bombed by Italian and German warplanes 23 during the infamous Spanish Civil War. Spanish nationalists had requested them to do so. The artist created this painting from his Paris home in response to these bombings.

The artwork was first exhibited at the Paris International Exposition of 1937 and put on several world tours to raise relief funds for the victims of the Spanish war. Due to its powerful message, the painting immediately became famous worldwide and played a crucial role in bringing the world’s attention to the civil war in Spain. The artwork became a standard for anti-war support and embodiment for peace.

Historical Context of the Painting

More than eighty years ago, Picasso undertook a commission that would change both the outlook of contemporary art and his career. The attacks on the town of Guernica that sparked the creation of the painting led to the destruction of three-quarters of the ancient city, maiming and killing hundreds of civilians. Picasso’s painting, Guernica, depicted the horrors of that war comprehensively, and in the process, becoming a universal symbol of anti-war.

The Spanish Republic had approached Pablo Picasso to create an artwork for its exhibition at the 1937 Paris International Exposition. At the time, the Soviet and German pavilions were massive architectural demonstrations of authority and power. Still, the cash-strapped Spanish Republic decided to go for something modest by using powerful modern art.

The Spanish called upon artists at the vanguard of the 1930s avant-garde, including the likes of Alexander Calder and Joan Miró 4. In 1937, Pablo Picasso accepted the commission and agreed to create a mural-sized piece for his native country.

Originally, Picasso had a different plan for his painting. Despite the Spanish Republic insisting that the artwork must convey a strong political statement, he had an apolitical piece in mind. The initial idea for the artwork was a composition depicting a painter inside his studio facing a naked model lying on a sofa.

But what would happen a few moments in the ancient town of Guernica would change Pablo’s mind and the course of his design.

On April 26th, 1937, Francisco Franco of Italy hired Fascist German to bomb Guernica. The timing of the bombing could be any worse, as it was on a market day, which meant the town was filled with women and children since men were off in the war fields. The town of Guernica was chosen because it was the first place in the Basque region of Spain where democracy was recognized.

Hundreds of people lost their lives on that fateful day, marking the first instance where defenseless civilians were targeted during the Spanish Civil War. At the time, Picasso lived in Paris, so he learned of the full extent of Guernica’s destruction through the daily newspaper. Pablo was devastated by the images of the event.

Pablo was a devoted leftist. The bombing of Guernica affected him profoundly, particularly since he received a lot of criticisms for not fighting in World War 1. Several days later, Pablo began to work on new sketches for the commission in his Rue des Grands Augustins studio.

In less than two months, the powerful painting was completed. Dora Maar, a surrealist 5 artist, was present during the creation of the piece and captured various stages of Guernica’s composition in a series of images.

In July 1937, Pablo delivered the completed work to the Spanish Republic pavilion. It immediately became the focus of the exhibition. Guernica was placed in the middle of Calder’s Mercury Fountain and Miro’s The Reaper.

Later in the 1940s, the Fascist Germans invaded Paris. One officer visited Pablo’s studio and asked, “Did you do that?”. Pablo answered, “No, you did.”

Guernica at a glance

This piece was painted in oil and monochrome colors of white, black, and grey. The combination of these three colors further emphasizes the gravity of the event portrayed in the painting. Pablo placed several symbols within the artwork. The dominant motif is that of suffering. Upon looking at the work, you can see a frantic tangle of six human figures, a man, a child, and four women, a bull and a horse.

There is an overhead lamp, under which the whole event transpires, in an enclosed low-ceiling studio-like space. The bright light bulb is considered a symbolism of the bombing since Spanish words for light bulbs and bombs sound very similar.

Picasso included traces of his original idea, a painter in a studio with a naked model lying on a sofa, in Guernica, such as the interior of what was supposed to be an artist studio.

Why is Picasso still important?

Before we proceed with more details about the painting, perhaps we should glance at the man behind this famous piece of work.

Pablo Picasso is one of the most influential artists of all time and dominated most of the 20th century. He is also one of the pioneers of the cubism form of art and invented collage, and played an essential role in the development of Surrealism and Symbolism.

It is practically impossible to talk about any of Pablo Picasso’s works without mentioning his role in Cubism, Surrealism, Symbolism, and his invention of collage. Above any other medium, Picasso considered himself a painter, even though his sculptures were massively influential and experimented in diverse areas like ceramics and printmaking.

In terms of personality, Picasso was famously charismatic, which you can tell by his painting style. One way or another, his personal relationships found a way into his art and directed its course. At the same time, his demeanor has come to personify that of the popular imagination of the avant-garde modernist.

Those outside the art world may be wondering what it is about Picasso’s work that moves everyone around the world? Why is it that many art commentaries still persist on elevating his status as the most influential artist of the past century, even though his work may be mistaken for a drawing of a crayon-crazy 5-year-old?

The answer to those questions and many others comes down to what we mentioned a few paragraphs above – his contributions to Cubism, Surrealism, and Symbolism.

Surrealism

Surrealism can be defined in a nutshell as intentionally abstract. It was invented as a response to realism, and many artists at the time used it to help the audience better comprehend the emotion of the scene without getting overwhelmed by the details within the scene.

Picasso also combined Symbolism with Surrealism. This sounds a little bit counterintuitive – to place specific objects within a scene so that it can better convey the message, while concurrently, you want the viewer to avoid concentration on other objects within the same scene – but nevertheless, he was best at threading that line very finely, perhaps because of his involvement within cubism.

Cubism

For us to really decipher Guernica, we must understand how cubism works. In Cubist art, objects are analyzed, taken apart, and reconstructed in discrete form. This way, Picasso could use a Surrealist view to highlight the emotion of a piece while still allowing the viewer to evaluate the scene and understand what the artist meant.

While neoclassical and classical painters tend to reproduce the world precisely the way it is in reality or a flawless version of it, Cubists artists like Pablo were willing to depict the world in more abstract forms that provided new, unmanageable visions of reality.

At its core, the concept of cubism includes the painting of a human figure, an object, or a scene from multiple angles. Pablo notoriously used this technique to simplify and filter any 3D subject into a pluriform, “Cubist” shape. Pablo was also massively inspired by the carved, rawboned forms of African masks, a motivation seen in Guernica and many others of his paintings.

This different form of Cubist pieces called Analytic Cubism, to separate it from another different kind, collage-style pieces called Synthetic Cubism, is characteristically broken up into geometric sections, sometimes divided by angular lines to create divisions between the different viewpoints being shown by the painter.

Though Guernica has fewer geometric features than some of Pablo’s previous Cubist pieces, its flattened, shifting perspectives and basic color palette are clear tags of the Cubist art.

Abstract art

Ultimately, Pablo and his Guernica were both exceptionally effective in shifting the art world towards modernism and what we now understand as abstract art.

Pablo considered painting to be a personal experience that should connect with his inner self, and soon, the internal space of his work transformed into claustrophobic. This change happened at the same time the world was engulfed in war and a period in which Pablo and his peers (Surrealists) were probing the dark corners of the human essence. During this time, he painted The Three Dancers (1925).

Symbolism

The most dominant theme in most of Pablo’s bodies of work then was women. Having experienced rough and numerous relationships, Pablo presented his lovers with a great deal of affection in his private work. Still, his public works tend to follow a much grayer perspective.

A few moments before creating Guernica, his pieces and drawings exposed much of Picasso’s reflections on symbolism as depicted by the female anatomy modulation. And these experimentations and the unique treatment of pictorial space, as mentioned above, filtered into Guernica.

Guernica’s style

But does this short story about Picasso’s previous work and his art style matter so much today? We had to deviate a little and cover the facts above because, even though Guernica was painted hastily, it didn’t come out of the blue. It resulted from many decades of artistic production and diverse visual experimentation and Picasso’s personal interest in the tense politics in his native Spain.

The painting is a finale of Pablo’s artistic undertakings and exploration of inner life, a work that can simply not be evaluated without looking at the bigger picture.

In so many ways, Guernica can be viewed as Picasso’s crown artwork. All of the visual aspects he mastered throughout his career were featured inside the composition of this painting. As a result, no other piece came close to reaching the sort of cult status it possesses.

Now, with that little digress, let us get back to this one of Picasso’s most notable works.

Analysis of Guernica

The visual impact of this artwork is derived from its set of dying and mutilated figures, presented in a stark black, grey, and white on a large canvas. We have already covered the primary motivation behind the creation of this painting: The bombing of Guernica. However, Pablo included numerous symbols to help the artwork convey deeper meaning for himself and the people of the Spanish Republic.

In our detailed analysis of Guernica, we will break down the painting into three segments: color and style, the symbols included within the canvas, and the human figures.

Let’s get started:

The meaning of Guernica

There are several interpretations of the mural. While on one part it is clear that the mural speaks against the war, the horse and the bull, an iconic symbol of that region dating back to 200 BC 67, represents other characters in the Spanish culture. The bull has been used on several occasions as the motif of destruction.

It is believed that in the context of the mural, it could mean the onslaught of Fascists. Picasso later said that the bull also represented doom and darkness, which came later in the world and Spanish history. The horse, in this case, symbolizes the people of Guernica that were being bombed. This masterpiece is a combination of epic and pastoral styles. At the same time, the color brings about increased drama and creates a reportage quality that is similar to that of a photographic record.

The lack of color: Why is Guernica black and white?

Due to the gravity of the message needed to be conveyed by the painting, Picasso didn’t want to create any distraction by including bright colors, so he made the entire piece stark white, grey, and black. Initially, Pablo had painted a red tear on the crying woman’s face but eventually decided to remove it. In the final painting, there is no intended or unintended focal point.

Composition & Geometric Shapes

When one views this painting, the entire piece hits you all at once with the numerous visuals to process, and the nearer you get to it, the more it overwhelms you in the atrocities of war. The middle of this mural-sized painting is a heap of angular shapes, traveling across each other with ferocious energy. This piece’s composition is similar to that of a central triangle of conflict, bordered on the right and left sides by more personal monstrosities.

In one detail, the artist depicts a mother crying for what appears to be her dead baby on the left, and on the right side, a figure can be seen consumed in the flames of the burning structure, which despite its dispassionate black and white color, it is quite chilling.

The buildings within the painting are also fascinating because if you are not careful, you may miss them altogether. They fade into the background, overshadowed by the screaming figures and animals. But the longer you stare at the painting, the more of the stage in which the whole scene transpires you will see.

Perhaps the most visible spot is a thin roof that is turned on its side. There is a burning building, and around it, the empty windows and doorways that ogle like an empty eye socket and missing teeth in the dead skull of the Guernica town. Though the symbols and the figures within the painting are a general commentary on war, the overall setting of the piece represents the ancient town, blasted into debris by the aerial bombs, perfectly.

Painting techniques and materials

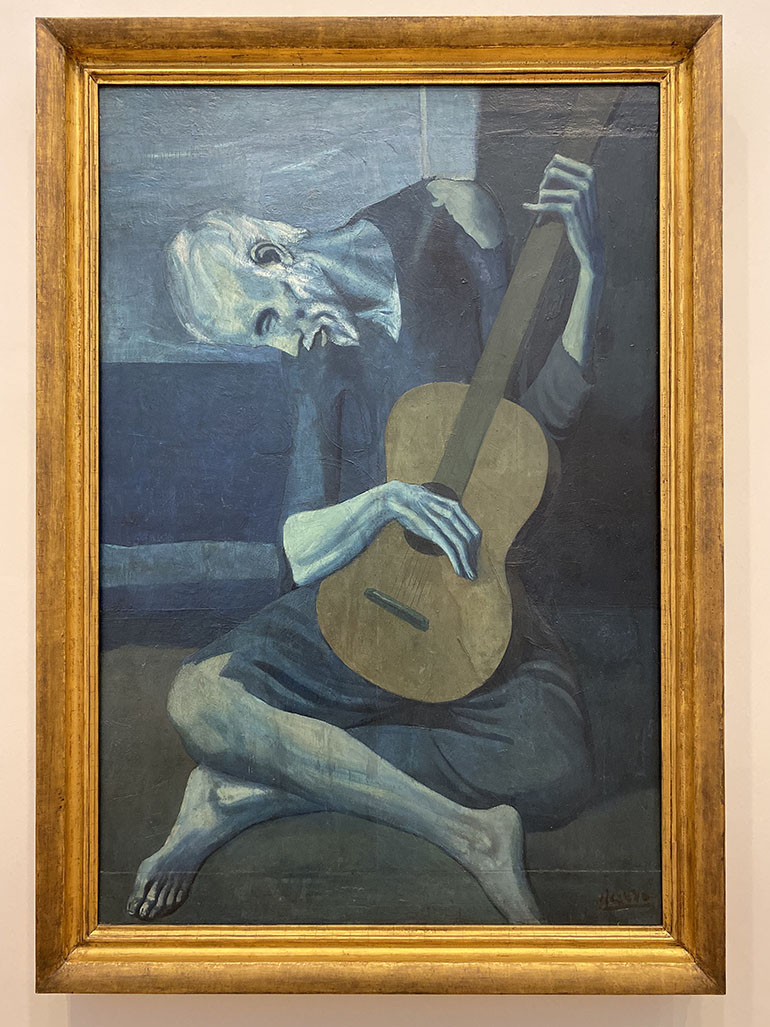

Though Pablo Picasso is known for his contemporary, abstract work, he had to learn to paint and draw realistically while still very young. His signature style of painting only started to appear when he was around 19 and living in Paris. Beginning with his well-known “Blue Period” and then immediately followed by the “Rose Period,” these phases were named so due to the predominant use of blue and pink colors throughout his work.

As he experimented more with cubism, he shifted to a narrow range of oil paints in subdued earth tones. The modern-day Pablo’s Cubist color pellet would contain colors like Burnt Sienna, Burnt Umber, Yellow Ochre, French Ultramarine Blue, Titanium White, and Ivory Black.

Picasso himself was believed to have used the Sennelier brand of hues, which had a firm feel valued highly by the Impressionists due to its ability to create thick spots on the painting; and was highly available in France at the turn of the twentieth century.

Picasso was also famous for discovering less “artistic” paints, such as those used in various industrial applications, and including them in his color palette. He also added some non-art objects. For instance, in Guernica, the artists included pieces of wallpaper for texture as well as some newspaper cuts. Sometimes he would also mix sand into his paints.

A classic cubist piece by Picasso may begin with a Burnt Sienna in the background and a basic painted sketch of the subject. By shifting his subject while painting, Picasso managed to layer several angles and perceptions into a single image.

Picasso was once quoted referencing his ever-changing style, saying:

It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.

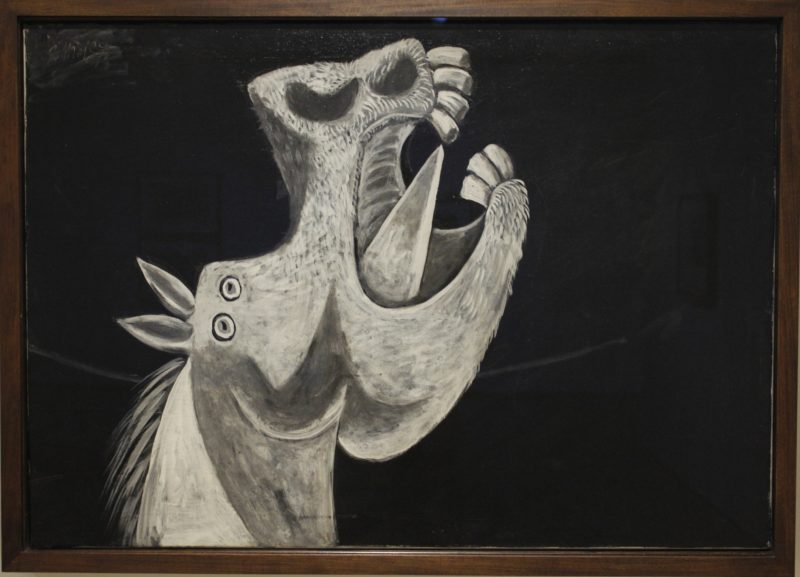

![Pablo Picasso – Study for the Horse Head [II], sketch for Guernica, 2 May 1937, drawing, installation view, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain](https://publicdelivery.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Pablo-Picasso-–-Study-for-the-Horse-Head-II-sketch-for-Guernica-2-May-1937-drawing-installation-view-Museo-Reina-Sofía-Madrid-Spain-800x1000.jpg)

Guernica & Surrealism

While the artist was never actually an official member of the Surrealist art movement, it is not hard to see its influence across Guernica. The terrifying figures and dismembered bodies dominate the painting. This painting blends cubist objects with a monochrome palette, which ultimately renders the piece more realistic. In so many ways, the Surrealist images in the artwork create a shocking depiction of suffering and war.

Looking at this painting, one can clearly see how the commotion caused by the political instability in Europe has been represented in its composition. Animals and humans are all muddled together into a background of broken solid-edge angular shapes, evocative of cubism style.

We can also see the newspaper cut in texture in the background, which is a throwback to Pablo’s early “Journal” cubist work. Though many within the art world tend to analyze Picasso’s use of color “blue” or “rose” periods, in the predominantly monochromatic Guernica, the primary color is black, perhaps suggestive of death itself.

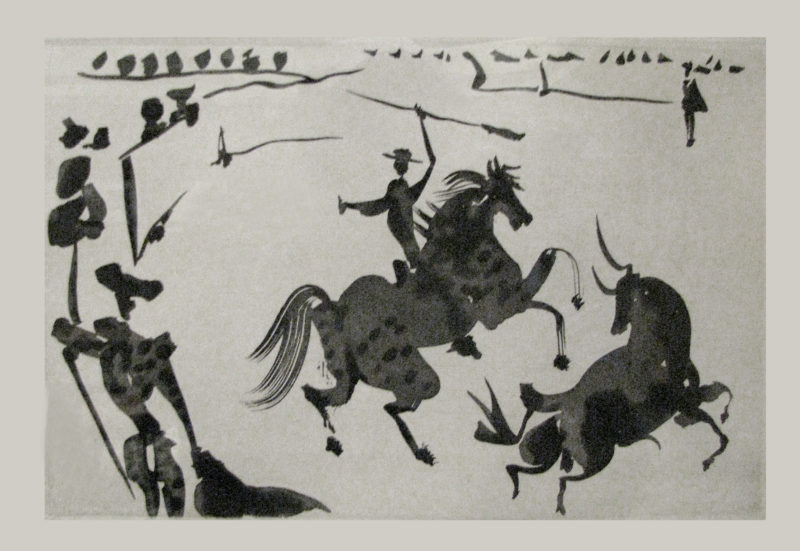

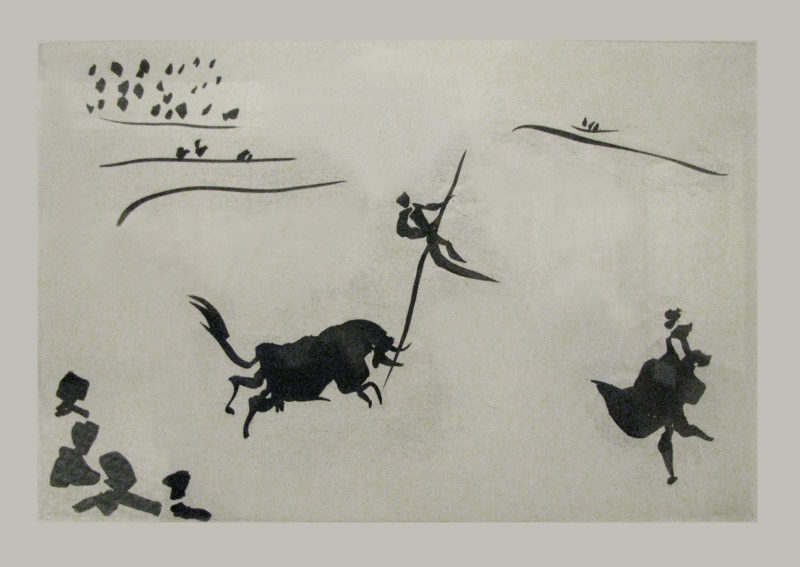

Guernica is also most likely to have been inspired by one Spanish artist known as Francisco de Goya, who mainly painted war portraits and bullfighting art. But does bullfighting influence the meaning of Guernica?

Does Guernica Have Another Meaning?

Picasso’s painting is made of humans and animals predominantly. The artist possibly displayed not only the concurrent dehumanization and brutalization of humankind during the war. He also showed the sweeping, animalistic response that every living thing, be it humans or animals, share in the face of atrocities and death. However, the bull and the horse in Guernica may have additional meaning from what we discussed elsewhere in this article.

Maybe Picasso also wanted to link bullfighting with the chaos in the scene of the painting. This piece undoubtedly can be categorized as a war painting, but at the same time, it also contains some other symbols that would very well fit the traditional art of bullfighting – a bull, a sword, a horse, and a man holding the said sword.

This is reminiscent of Picasso’s later art and paintings, such as the Tauromaquia (1957). In Guernica, the bull is an unofficial national emblem of the Spanish Republic, and bullfighting is an allegory connecting Guernica with an explicitly patriotic meaning.

If this painting depicts bullfighting, it is not the traditional Spanish bullfighting. In Guernica, instead of showing a triumphant matador bowing to the spectators before a defeated bull, Picasso depicts a stoically standing bull. In contrast, the supposed matador lays dead, and the spear or sword he might have used to defeat the beast is broken off in his arms.

Like the dead matador, his horse is also lying in the foreground, dying and suffering. It is not coincidental that only the bull is standing peacefully in Guernica, with the rest of the figures and the portrait’s composition spun toward the animal, an improbable peaceful centerpiece of the war-painting.

Even though Pablo himself did not like to talk about Guernica’s “meaning” and possibly all of his art, the nationalist symbolism of this painting is undeniable.

If you give a meaning to certain things in my paintings, it may be very true, but it is not my idea to give this meaning. What ideas and conclusions you have got I obtained too, but instinctively, unconsciously, I make the painting for the painting. I paint the objects for what they are.

As the unofficial emblem of the Spanish Republic and the most resilient figure in the entire painting, the bull is more than likely the representation of Spain itself, a nation that is still “standing” despite the savage attack.

Though the bull in Guernica is victorious, the general meaning of the painting is less cheerful. The pandemonium and cruelty rule over the people, much as it did in real life Guernica bombings. Nevertheless, the artwork is still considered one of the most powerful war paintings of all time. It has even been memorialized in the form of tattoos by many people, including in pop culture.

There is also a claim that Guernica may also portray the life of a painter. The original idea of the painting was about a painter in his studio with a nude model lying on a sofa. According to some art critics, this piece depicts three critical moments in Pablo’s life:

- His dreadful earthquake experience in Malaga when he was still a child

- His checkered relationship history

- Carlos Casagemas, a friend committing suicide

Going with this theory means that images in the painting also have a completely different meaning. For instance, the horse may suggest the symbolism of Olga Khokhlova, the artist’s first wife, who is usually represented as an animal in many other paintings by Picasso.

Video: What inspired Pablo Picasso’s masterpiece?

2 min 40 sec

The Symbolism in Guernica

The Symbolism in Guernica

Now let’s take a look at Picasso’s use of symbolism in Guernica as it refers to his anti-war message. These elements helped shed light on Pablo as an artist and how his remarkably effective use of symbolism placed him on a pedestal as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century.

Virgin and Child

If you look closely underneath the bull, you will see a woman clutching her dead child, with her head facing the heavens in grief-stricken cry and her eyes drawn in the shape of tears. Picasso meant to create similarity here with the image of the Virgin and Child, an archetypal catholic image, only in Guernica, it is tainted by war.

The depiction of this image is also similar to the painting of Dora Maar, which Pablo had nicknamed “the woman who cries.”

The Dead Soldier

Moving your eyes further down, you will see a fallen soldier on the ground. However, the figure of the dead soldier does not have complete body parts. Instead, fragmented pieces are scattered around the floor. More visible are both his arms and the head. One of his arms clutches on a broken sword while the other has a flower. This is the only figure lying down in the painting, representing his gallant yet fruitless attempt to fight back against the horror. Perhaps the ghostly flower in his other arm is symbolic of hope despite the atrocities, just like the cloaked light provided by the kerosene lamp.

The Bomb and the Light Bulb or God’s Eye

Above the setting of the painting is a light bulb, burning brightly. The meaning of this particular object is a topic of heated discussion among scholars. However, it is widely believed to contain several translations.

First, Picasso deliberately shaped it like an eye and positioned it above everything else, leading many people to think that the light bulb represents God’s eye as he watches all the destruction and chaos caused by war.

Others believe that it signifies technological advancement since it is placed directly next to an oil lamp. There could be some truths in this comparison since Italy and Fascist Germany agreed to bomb the town of Guernica so that they could test out their recently developed weapons in a live battle setting.

Another translation, especially for those who speak Spanish, is that the light bulb could also mean the bomb. Both bulb and bomb have almost similar pronunciations in Spanish: bombilla and bomba. This comparison is also quite striking as it explains the light bulb’s position at the top, from where the bombs were dropped.

The War Horse

At the center of the painting, you can see a warhorse. The horse appears as if it is about to fall as a result of sustained wounds. However, the only part of the horse visible is the head with its mouth wide open as it stares at the horrors of war. The remaining parts of its body are covered by other figures in the painting, ultimately forming additional images like the human skull.

The horse signifies the suffering inflicted on the people by the German and Italian dictators.

The Injured Woman

At the bottom right corner of the painting, you find a woman with a wounded leg. She is bleeding profusely from the knee and covers her wound with her hand to stop the bleeding.

The Bombing Victim

Just above the injured woman is the bombing victim. The man can be seen pleading at the sky, seemingly to a god, or perhaps to the German bombers to stop them from causing further destruction. As the man continues to implore, the building continues to be ravaged by fire and crumble around him. This image became a powerful artistic depiction of the anti-war message conveyed by the painting.

The Spirit of the Spanish People

One of the four women in the painting is holding an oil lamp. Looking at her closely, she appears shocked and bewildered. The woman can, however, be translated to mean the ghostly depiction of the Spanish Republic.

Now that we have seen what the figures in the painting mean, the anti-war message is clear as intended by Picasso. As you move your eyes across the canvas, the death, mutilation, destruction, and anguish are all very clear.

However, the artist did include another element into this piece, and if we can look closely enough, it is there to be seen. Hope.

The Hope Within The Painting

There are three elements of hope in this painting, though they are somewhat hidden in the chaos.

The White Poppy Flower

The poppy has long been used as a symbol of peace, and Picasso, whether intentionally or not, included it in Guernica to convey that same message – of hope and peace.

The first image of hope was the ghostly flower in the hands of the dead soldier, though it was quite odd to place it there since soldiers are not really known for carrying flowers, especially on battlefields.

Nevertheless, this flower image is used to send a message of peace that would come in the aftermath of the commotion. Looking closely at the flower, it looks like a white poppy flower. Since the end of World War I, poppies have been widely used as symbols of peace and the end and commemoration of war victims.

The Dove

The second image of hope in the painting is a small dove placed between the horse and the bull. Though it is not clear, the bird is just like a flash of white.

Because the Catholic Church depicts the Holy Spirit as a white dive, many believe that the inclusion of the white bird in this painting may represent the Holy Spirit starting to break past the darkness of the chaos around it and usher in peace.

The Lamp

The last sign of hope is an oil lamp. If you can look at the entire painting closely, you will see that the source of the scene’s lighting is not the electric bulb dangling at the top but the oil lamp immediately beside it.

Though it is small, the flame is strong enough to provide light to the entire setting, and if it is indeed the spirit of the Spanish people that exerts it, then it is a source of hope for everyone in the scene. This comparison would explain why the wounded woman below looks yearningly toward the oil lamp.

Guernica in the last century

First exhibited in 1937

First exhibited in 1937

After the completion of the painting, Picasso toured the world and got the Spanish Civil War 1011 to the attention of the world. In the process, he also became famous and created other masterpieces that also gained a lot of attention. Guernica was displayed at the Paris International Exposition 1213 at the 1937 World Fair.

The Aftermath of the Paris Expo

Following the completion of the Paris Expo, the painting was sent on a worldwide tour by the Spanish Republican forces to drum up awareness of the war and raise relief funds for the victims. The artwork traveled the world for the next 19 years, including places such as Brazil, England, and Greece.

But fearing the Fascist invasion of Paris, Pablo decided to loan the painting to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. It continued its voyage, touring the United States and beyond. The world tour made the painting even more famous and stirred heated debates on Pablo’s style of art, literary sources, the symbolism of its figures, his thought process, and many other topics.

In the late 1950s, the painting was returned to MoMA as years of travel worldwide had taken their toll.

Guernica now

Where is Guernica currently located

Where is Guernica currently located

Pablo’s wished that the canvas must not be returned to Spain until dictator Franco was dead. Apart from Pablo’s personal disdain for Franco’s dictatorship, the artwork would have been destroyed if it had been returned to Spain during Franco’s reign.

After the passing of Franco and many years of negotiations, the Museum of Modern Arts restored the painting to Spain in 1981, to the Cason del Buen Retiro, a branch of the Prado Museum in Madrid, as per the wishes of Picasso. However, Picasso never witnessed the return of the painting to his homeland, as he died in 1973, two years before dictator Franco.

A decade later, the artwork was transferred to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, where it is housed to this day. However, the move defied Picasso’s expressed wish to have the painting placed among Prado’s great pieces.

Guernica is in the permanent exhibition of the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain

- The Museo Reina Sofia currently houses Guernica in room 2006 on the second floor of the Sabatini Building.

- Calle de Santa Isabel, 52, 28012 Madrid, Spain

- Hours of the Museo Reina Sofia 14

Ownership of Guernica

Initially, Picasso had created the painting as a gift to the Spanish people, but its ownership has been a subject of many legal battles. During the commission of the artwork, the Spanish Republic gave Picasso a total of 150,000 French francs to cover the expenses of creating Guernica ($135,000 in today’s value).

So it is not clear whether that constituted a buying-selling transaction or not, though sources close to the artist claim that he did not consider it a sale. On the other hand, the Spanish government says that it either commissioned or acquired it in 1937.

More confusingly is that Picasso himself exhibited the painting at the Paris Expo in 1937. It was also featured in several other exhibitions worldwide before personally entrusting it to MoMA from 1939 until 1981, with instructions that MoMA would keep the piece until Spain was democratically stable.

When the painting was returned to Spain, it was done through an agreement with Picasso’s legatees, the Spanish government, and MoMA.

Pablo Picasso – Minotauromachy (La Minotauromachie), 1935, etching and engraving, 49.6 x 69.6 cm (19 1/2 x 27 3/8 inch), edition of approximately 55 (inscribed 50), photo: CC BY-NC 2.0 81 by Txeng 82

How much is the painting worth today?

Since the painting has never been sold at an auction, it is not easy to determine its value. But using the historical norms, where several of Picasso’s paintings have sold in excesses of 100 million dollars, it is safe to hypothesize Guernica’s value.

Given its mural size, which is larger than other Picasso’s paintings, coupled with its powerful and historical importance, its value would undoubtedly be more than 200 million dollars in today’s market if it went up for auction.

Conclusion

Picasso had initially been commissioned by Spain’s Republican government to work on a mural for the Paris Exhibition. However, when he learned of the bombing in his motherland, he abandoned the original idea and began working on something that showed his displeasure for the war. This piece did not gain attention at the exhibition but became famous when people connected it to what was happening in Spain.

Explore nearby

Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain

Joan Miró's largest artworks5 km away

Joan Miró's largest artworks5 km away