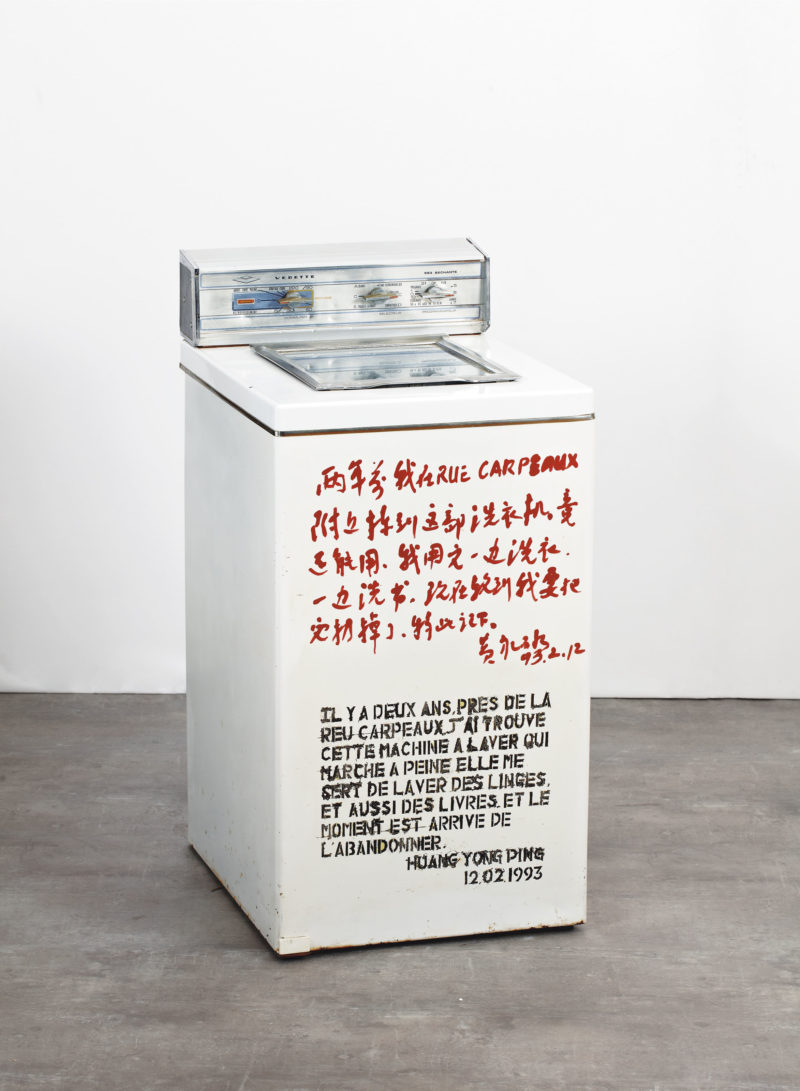

The inscription on the exterior of the machine says:

Two years ago, I found this washing machine on rue Carpeaux, but it is not functional. I’ve used it once for washing clothes and once for washing books. Now it is the time to throw it away, herby noted down.

Introduction

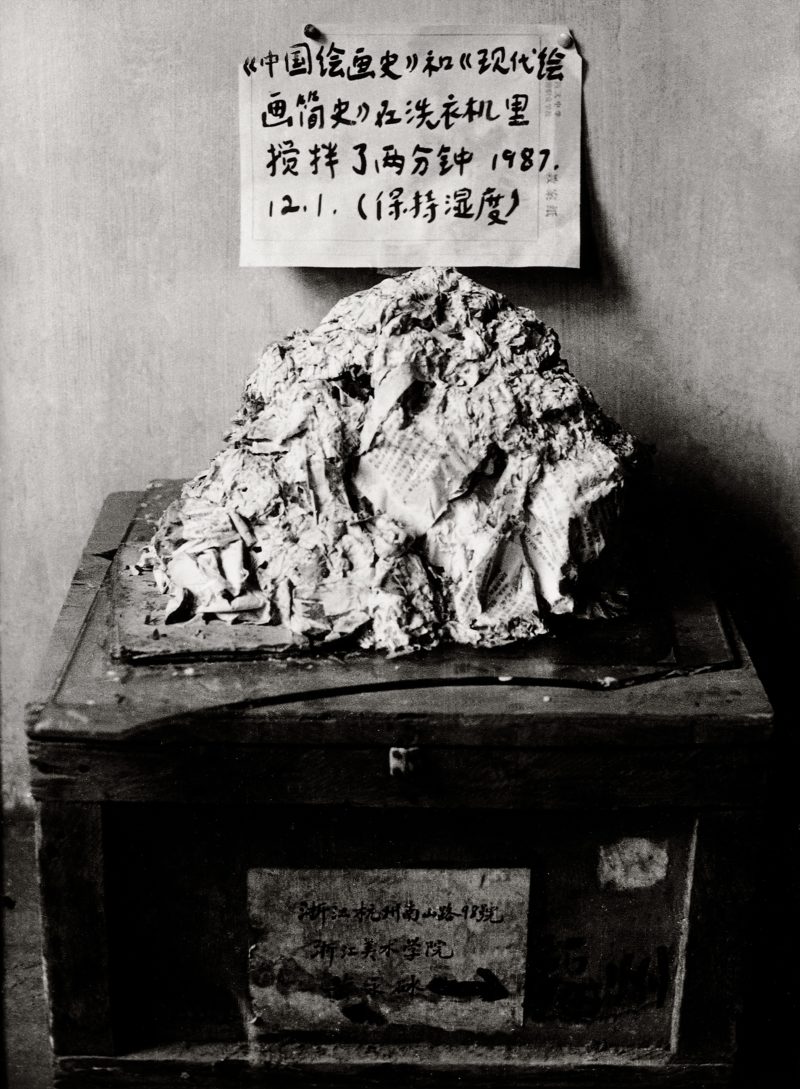

Imagine inserting two historical books representing various cultures into a washing machine. Then, instead of removing them quickly, you continue washing them for a whole two minutes. That’s what the Chinese artist Huang Yong Ping 1 did on December 1, 1987.

Art history washed in washing machine

He took two books, a classical history book on Chinese art and one on the history of Western art, placed them inside a washing machine, and left them there for a couple of minutes. The result was a pile of ineligible text.

![Huang Yong Ping - The History of Chinese Painting and the History of Modern [Western] Painting Washed in the Washing Machine for Two Minutes, 1987](https://publicdelivery.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Huang-Yong-Ping-The-History-of-Chinese-Painting-and-the-History-of-Modern-Western-Painting-Washed-in-the-Washing-Machine-for-Two-Minutes-1987-.jpg)

Ideologies that define Huang’s career

Huang Yong Ping was born in China. Later, he moved to the West, where he participated in various art exhibitions. For the most part, one can divide his work or career into two phases.

First, his career is mostly defined by his focus on Chinese issues. Second, one clearly sees the influence that Western culture has on his artistic mind. Providing a good explanation regarding his career depends on your starting point. Those in the West saw him one way, while art lovers in China also had a different view of Huang.

Cricism & praise

In the eyes of many in China, Huang’s previous artworks show a man who was not only free but also subversive to express himself artistically. Later, the same people believe that Huang sold out his ideals to the Western world.

On the other hand, you have those in the West who view his previous works as the result of living and working in an authoritarian system. Upon displaying his pieces after returning to China from his sojourn in the West, they claim his skills and career blossomed.

Whatever the case, the two groups agree that Huang Yong Ping changed after returning from the West. It’s well worth pointing out that Haung’s career had already taken off prior to his departure to the West.

n terms of contemporary art in China, his reputation was already quite solid before leaving for France. However, in his words, Ping says that his methodology never departed from what it was before he left China.

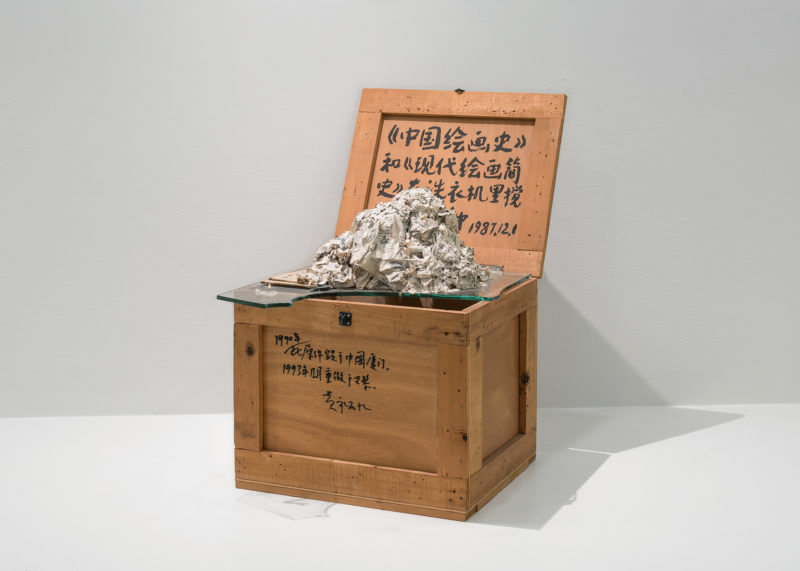

The text on the work reads:

A brief history of Chinese painting history and modern painting was stirred in the washing machine for two minutes.

1990: This piece was destroyed in Xiamen, China.

Redone in Paris in February 1993

Influences

Furthermore, it’s also not in doubt that Huang’s artistic career owes much to the following influences in his life: Ludwig Wittgenstein, Michel Foucault, Martin Heidegger, Roland Barthes, as well as Zen and Taoist philosophy.

Why did he wash the books?

Based on all that, it’s clear to see why Huang could wash two historical books in a washing machine. In fact, he says that he washed the two books to prove their worthlessness. Essentially, he’s saying that they are not as important as is generally believed.

It’s also important to state that Huang had a reputation for washing books. What is more, this wasn’t the only occasion that he washed books as a form of artistic expression. However, what is clear is that he found a unique way of using his artistic talent to inform the world of his ideologies.

Magiciens de la Terre (The Magicians of the Earth)

Huang rose to fame in Europe when he first showed his washing machine in a now-legendary exhibition in Paris. In 1989, from May 18 to August 14, the Centre Pompidou and the Grande Halle de la Villette hosted the legendary exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (The Magicians of the Earth).

The show surprised audiences and critics as well as the art market at the same time. During this time, the contemporary art world was limited to the perimeter of the borders of Europe and North America. The show featured 50% Western and 50% non-Western artists.

For this exhibition, curator Jean-Hubert Martin invited artists from all continents, which he discovered one by one during long research trips. Martin especially focused on techniques inspired by ancient cultures and followed a post-colonial approach, and, in the process, unearthing “invisible” artists who were unknown and marginal in their countries.

This groundbreaking initiative was widely regarded as pioneering and matched the timing of the dawn of globalization and marked a turning point in curating and contemporary art history, creating a timeless legacy for this outstanding curator.

Amongst the 101 artists 23, some of the most prominent were Marina Abramović 4 (Serbia), John Baldessari 5 (US), Alighiero Boetti 6 (Italy), Christian Boltanski (France), Louise Bourgeois 7 (France), Neil Dawson 8 (New Zealand), Braco Dimitrijević 9 (Bosnia), Hans Haacke 10 (Germany), Huang Yong Ping 11 (China), Alfredo Jaar 12 (Chile), Anselm Kiefer 13 (Germany), On Kawara (Japan), Barbara Kruger 14 (US), Richard Long 15 (UK), Nam June Paik 16 (South Korea) and Jeff Wall 17 (Canada).