C/ de Ferlandina, 25, Ciutat Vella, 08001 Barcelona Copy

41.382762, 2.166069 Copy ✓verified

Accessibility

The mural is easily accessible as it's located on a public street. The sidewalk in front of the mural is wide and flat, making it wheelchair accessible.Before you go

Be respectful: Remember this is a residential area.

Camera ready: The colorful and vibrant mural serves as an excellent photo opportunity.

Explore the area: El Raval is known for its diverse culture and street art. Consider taking a walking tour of the neighborhood.

No entrance fee: Freely visible to the public at all times.

Visit duration: Viewing the mural itself takes about 10-15 minutes, but allow extra time to explore the surrounding area.

Best visit time

Visit early morning or late afternoon to avoid crowds and experience how the light enhances the mural's vivid red color.At night, the mural is well-lit, offering a different viewing experience.

Directions

Liceu Metro Station

Lines: L3

Walking distance: 800 meters (10 minutes)

Universitat Metro Station

Lines: L1

Walking distance: 270 meters (4 minutes)

Free

~20min

Introduction

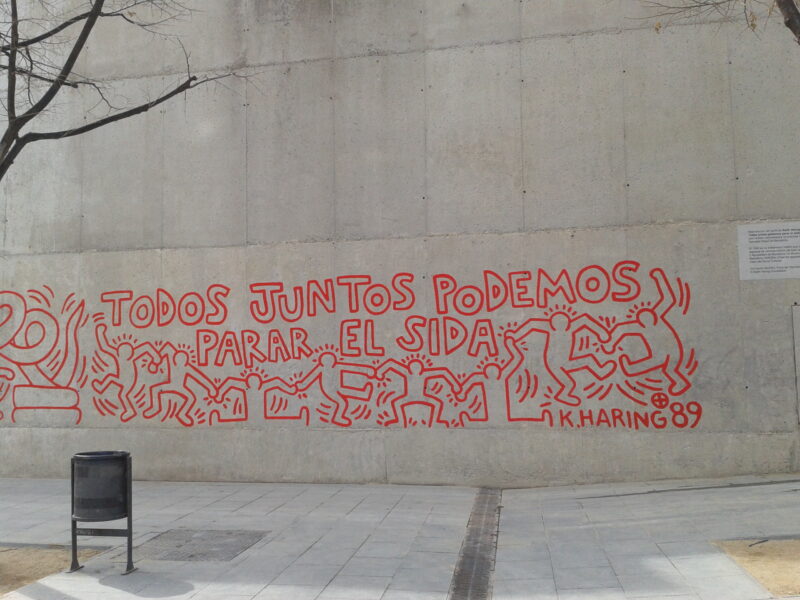

A vibrant red mural in the heart of Barcelona 1 serves as both an artistic expression and social activism 2. Officially known as the Todos Juntos Podemos Parar el SIDA (Together We Can Stop AIDS), the public art was created by the renowned American artist and AIDS activist Keith Haring 3 in 1989.

More than just a work of art, this mural represents a powerful call to action against the AIDS epidemic that was ravaging communities worldwide at the time.

History

The story of Haring’s Barcelona mural begins with a chance encounter. In February 1989, Haring was in Spain 4 for the ARCO art fair in Madrid 5. On his way back to New York 6, he made a brief stop in Barcelona, where he attended an art reception at the Joan Prats Gallery. It was here that he met an old friend from New York, Montse Guillén, the owner of the famous El Internacional Restaurant in TriBeCa.

Guillen, recognizing the unique opportunity presented by Haring’s presence, asked if he would consider creating something in Barcelona. Haring agreed, but with one condition: he wanted to choose the location himself. Local authorities, including influential politician Ferran Mascarell, helped secure the necessary permissions.

Haring selected a wall in Plaça de Salvador Seguí, in the heart of El Raval – then known as Barrio Chino, a neighborhood notorious for its high crime rate and drug problems. The choice was deliberate; Haring was drawn to the area’s gritty authenticity, reminiscent of the marginal neighborhoods in New York where he first began painting.

On February 27, 1989, Haring arrived at the site with his boombox blaring acid house music. Without any preliminary sketches, he began painting directly on the slanted, dirty wall. Over the course of five hours, as curious onlookers gathered, he transformed the blank space into a powerful visual message against AIDS. It was later revealed in an event attended by local leaders.

However, the wall suffered from the elements and was defaced with graffiti. Since 1996, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) has reproduced the mural several times on a concrete wall near its entrance, between Carrer de Ferlandina and Plaça Joan Coromines.

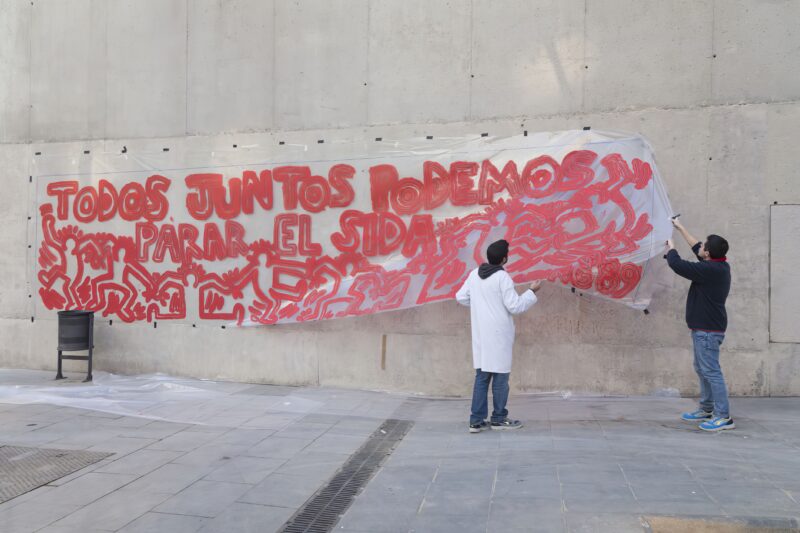

In February 2014, marking the 25th anniversary of the mural’s creation, MACBA, in agreement with the Keith Haring Foundation and the Barcelona City Council, recreated the mural once again.

| 1988 | Keith Haring is diagnosed with AIDS |

| Feb 1989 | Haring creates original “Todos Juntos Podemos Parar el SIDA” |

| Feb 27, 1989 | Mural is officially unveiled in an event attended by local leaders |

| Feb 16, 1990 | Keith Haring passes away due to AIDS-related complications |

| 1996 | MACBA recreates the mural for the first time near its entrance |

| Feb 2014 | MACBA recreates the mural to mark its 25th anniversary |

Composition

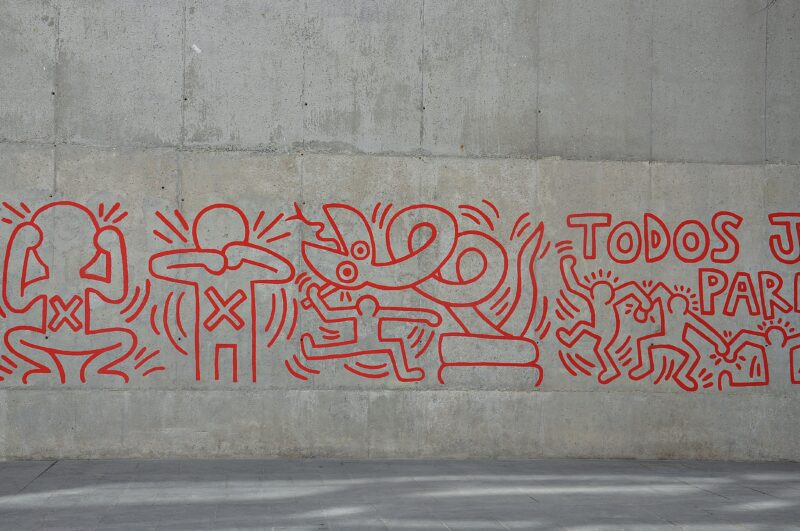

Todos Juntos Podemos Parar el SIDA speaks to Haring’s signature style, characterized by bold lines, vibrant colors, and symbolic figures. The mural spans 34 meters (approximately 111 feet) across a concrete buttress.

Haring chose to paint the entire mural in a striking blood-red color, a choice packed with symbolism. The color not only grabs attention but also alludes to the blood-borne nature of HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

The mural’s central image is a giant snake, symbolizing AIDS, which dominates the composition. To the left, four figures flee in terror with their hands raised, while on the right, two figures shaped like scissors attempt to cut the snake.

Another figure places a condom on the snake’s tail, a clear nod to safe sex practices. The snake clutches a giant hypodermic syringe, and nearby lies a prone figure, possibly representing a victim of the disease.

In the center, three larger figures adopt poses reminiscent of the “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” monkeys, symbolizing the willful ignorance and stigma that often surrounded the AIDS crisis.

Nearby, a couple embraces, seemingly oblivious to the danger around them, caught in the snake’s coils. Another scene shows a figure wielding a stake against a second, smaller snake.

Haring’s characteristic energy lines radiate from the figures, adding a sense of urgency and movement to the composition. The mural is topped with the phrase Todos Juntos Podemos Parar el SIDA (Together We Can Stop AIDS) in bold lettering, along with Haring’s signature.

Haring’s technique was as impressive as the finished product. He worked freehand without scaffolding or preparatory drawings. Still, he adapted his body to the wall’s awkward angle, creating what he later described in his journal 78 as “new positions to balance and keep the consistency required.”

Inspiration & symbolism

To Haring, the mural served as a personal fight against AIDS. Diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, just a year before painting this mural, Haring had become a vocal advocate for AIDS awareness and safe sex practices. He stated 910, “the disease that has taken the lives of some of my close friends has been an inspiration in my work.”

The mural’s imagery draws on Haring’s established lexicon of symbols, which he had been developing since his early days of drawing in New York City subway stations 1112. However, in this context, these familiar forms take on a new, urgent meaning. The fleeing figures represent the fear and stigma surrounding AIDS, while the scissors cutting the snake symbolize the hope for a cure or effective treatment.

The condom imagery was particularly bold for its time. In 1989, open talk about safe sex was still taboo in many circles, and Haring’s mural brought this message into the public space in a way that was impossible to ignore.

Context

In the late 1980s, Barcelona, like many cities around the world, was grappling with the devastating impact of the AIDS epidemic. Spain had one of the highest rates of HIV infection in Western Europe, and public awareness campaigns were still in their infancy. The El Raval neighborhood was particularly affected.

Haring, already an established artist and activist, painted his Barcelona mural just a year after his own AIDS diagnosis. It was a direct response to the global crisis, aiming to educate and provoke action in a city that was also battling the epidemic.

Public reception & controversy

When Keith Haring painted Todos Juntos Podemos Parar el SIDA, the mural sparked a mix of reactions from the local community. Some appreciated the boldness of Haring’s message. Others, however, didn’t receive the mural positively.

Some locals and officials were uncomfortable with the directness of the imagery, particularly the depiction of a condom, which was considered provocative in a conservative society. The mural’s stark red color and the confronting nature of its message also led to debates about its appropriateness in a public space.

According to his diary 1314, Haring even argued with a brothel owner in the area who was angry about the theme of the work:

He complained that the mural would only harm the neighborhood because people would think there were many drugs there and the police would close the bars. That’s ridiculous because people already know how bad the situation in the neighborhood is.

Over time, the mural’s status evolved, and it became a symbol of Haring’s legacy and Barcelona’s cultural landscape. The discussions it sparked, both supportive and critical, highlight the mural’s impact on public discourse around AIDS and the role of art in challenging societal norms.

Preservation efforts

The original mural was painted on a concrete buttress of a building slated for demolition in Plaza Salvador Seguí, in what was then known as the Barrio Chino (now part of El Raval). As the original site was demolished, preservation efforts began.

In 1996, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) took the initiative to recreate the mural on a concrete wall near its entrance. This relocation not only protected the mural from further damage but also integrated it into a more formal art setting, ensuring its visibility to a wider audience.

In 2014, marking the 25th anniversary of the mural’s creation, MACBA undertook a project to recreate the mural once again. This version, located at the original site, was designed to replicate the vibrancy and impact of Haring’s work, using modern materials that could better withstand environmental conditions.

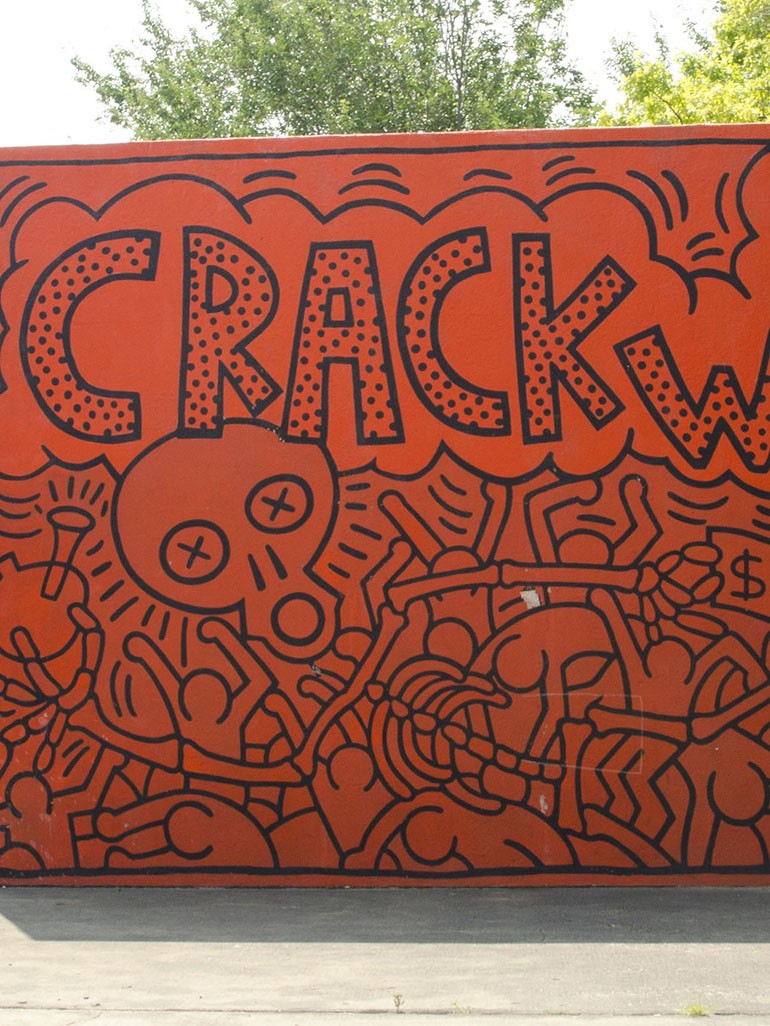

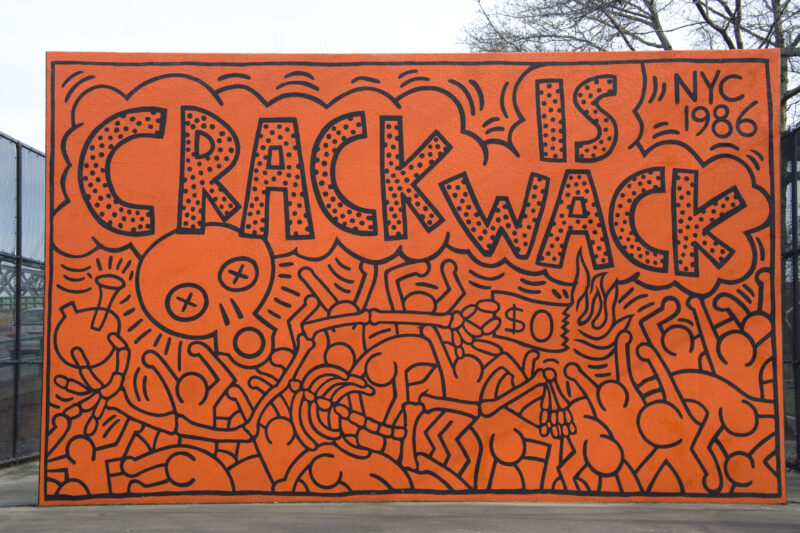

Crack is Wack

Keith Haring’s mural in Barcelona is one of several public works through which the artist addressed pressing social issues. Another notable example is his Crack is Wack 1516 mural in New York City, painted in 1986. While both murals share Haring’s distinctive style—bold lines, vivid colors, and symbolic figures—they differ significantly in their themes and intended messages. Both murals, however, are united by Haring’s commitment to using art as a tool for social change.

Keith Haring’s Legacy

Keith Haring (1958-1990) was one of the most prominent artists to emerge from the 1980s New York City art scene. He began his career drawing graffiti art 17 with socially conscious themes. Haring’s work often addressed political and social issues, including apartheid, the crack cocaine epidemic, LGBTQ+ rights as well as AIDS.

Final words

Art holds significant power to challenge, educate, and inspire. This mural, born from a chance encounter and fueled by urgent activism, continues to resonate in Barcelona and beyond.

As new generations encounter this vibrant work, one can’t help but wonder: How will future artists carry forward Haring’s mission of using art as a tool for social change? In a world still grappling with numerous crises, perhaps Haring’s bold call to action is more relevant than ever.