Who is Zhang Xiaogang?

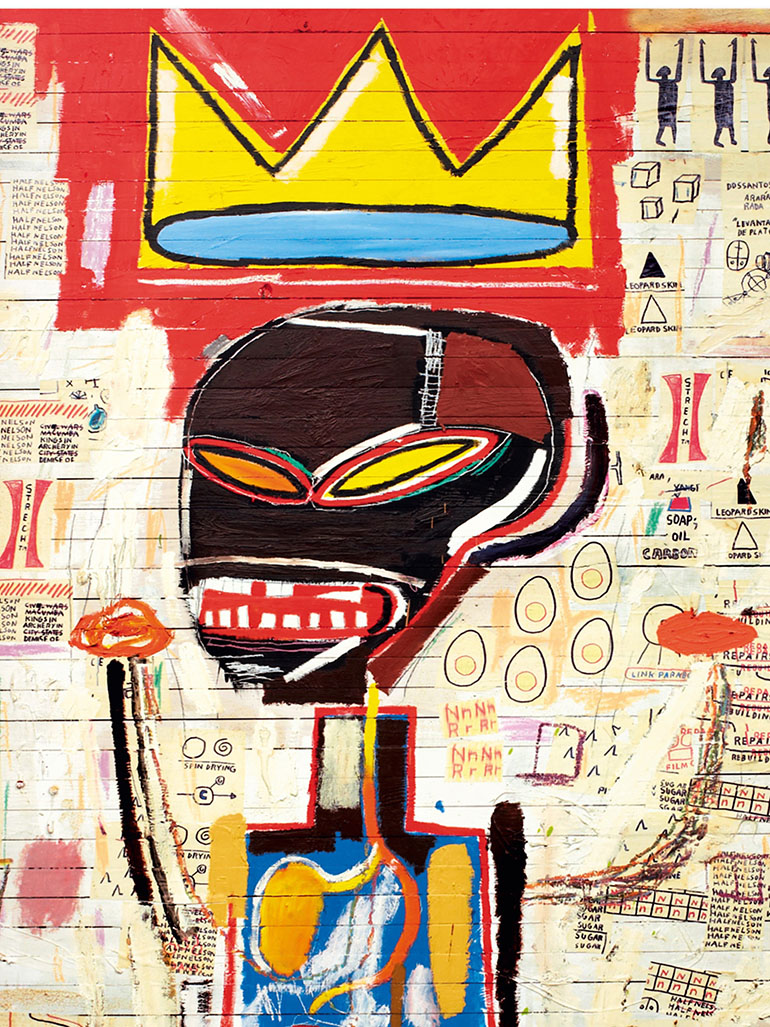

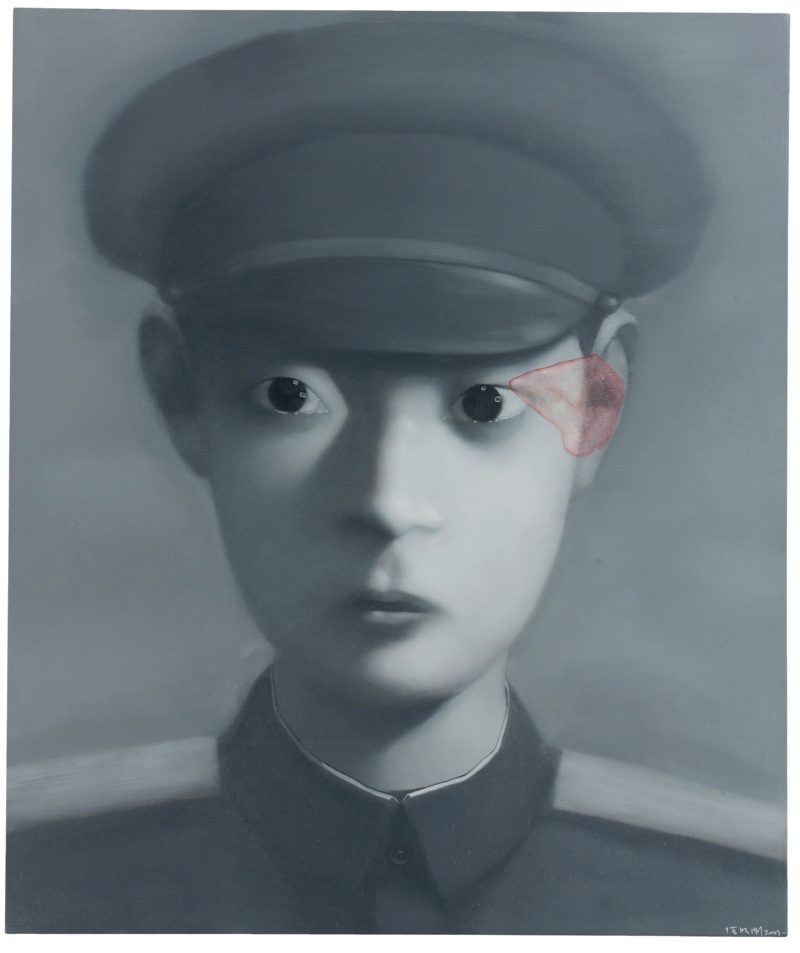

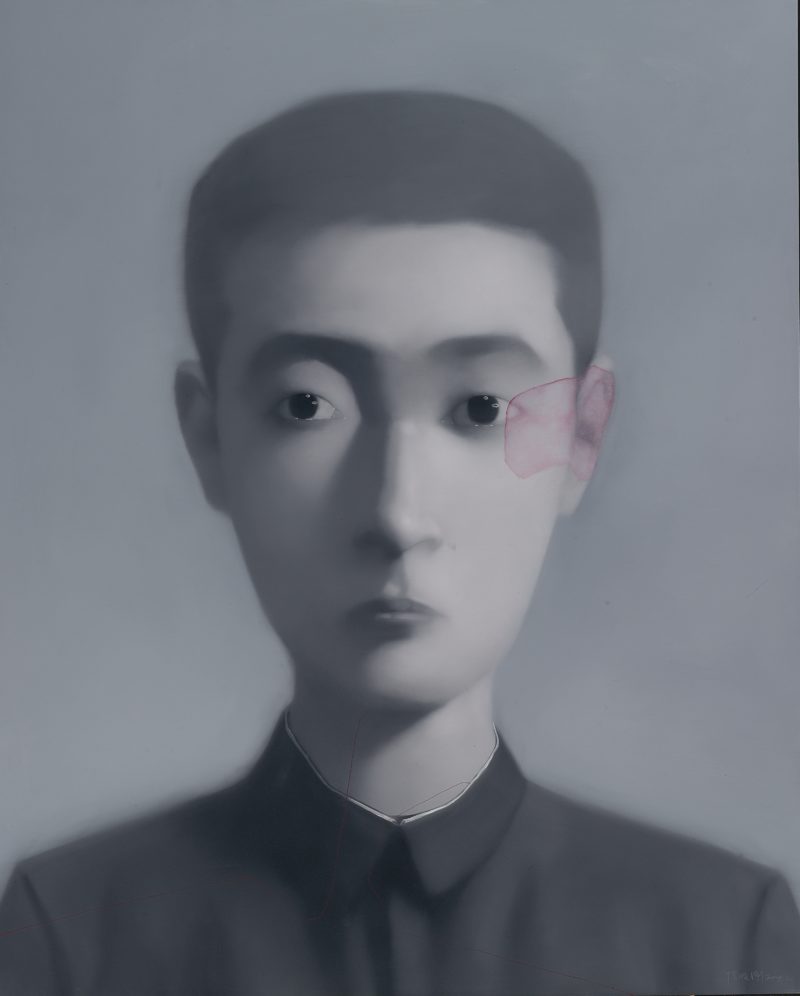

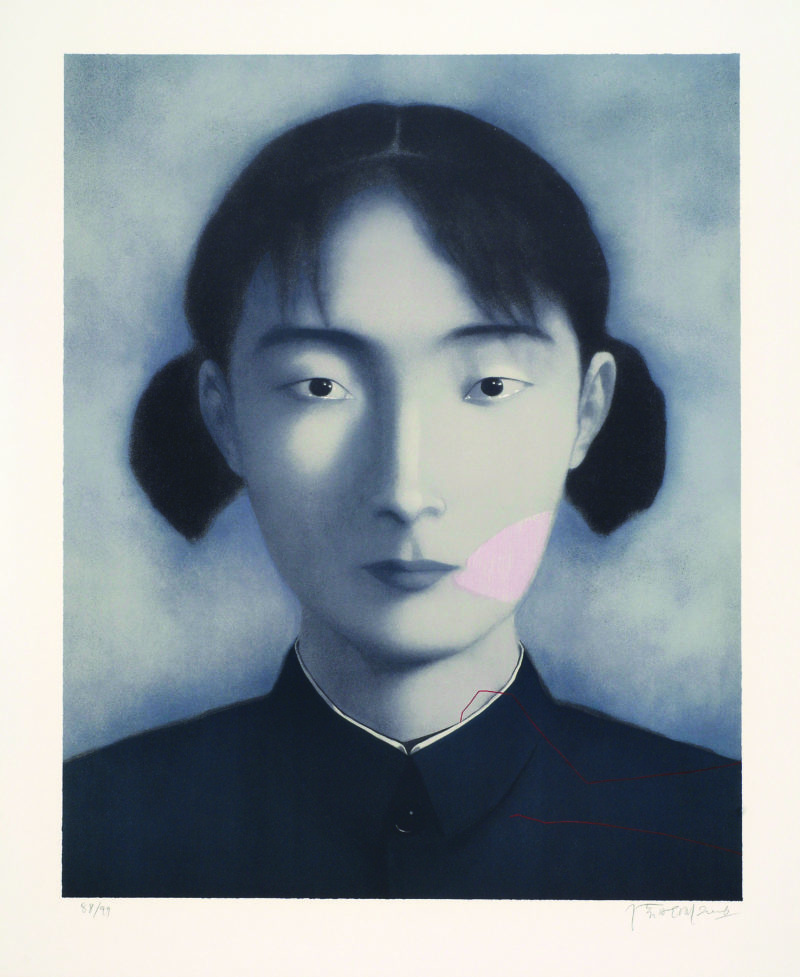

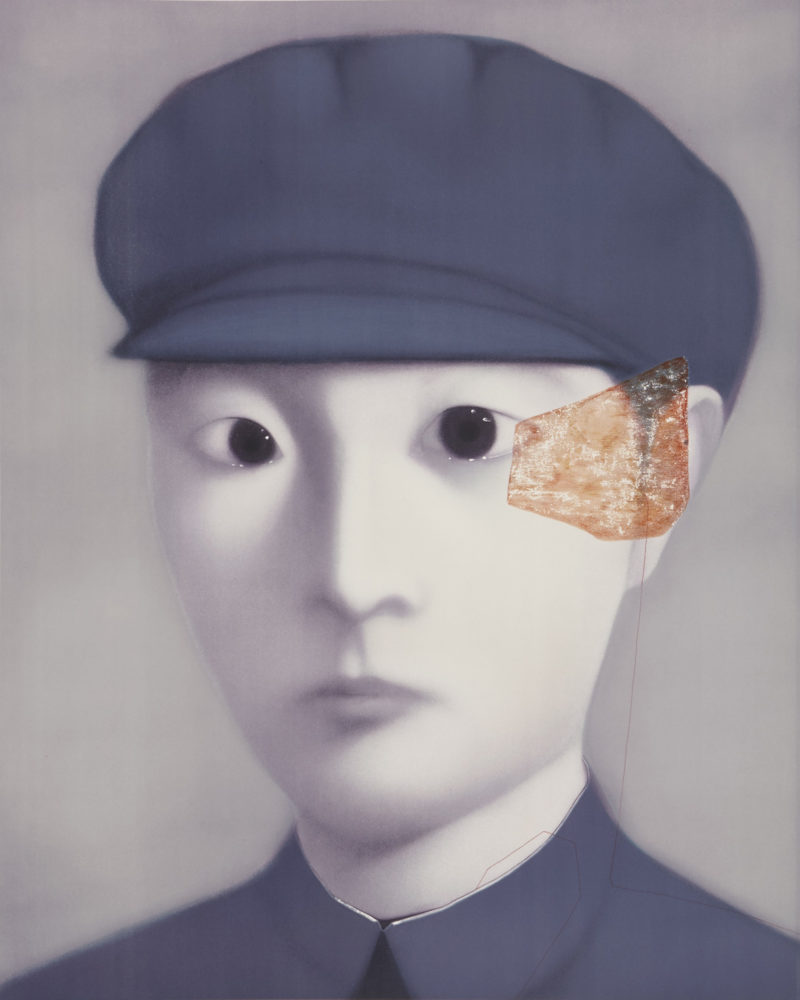

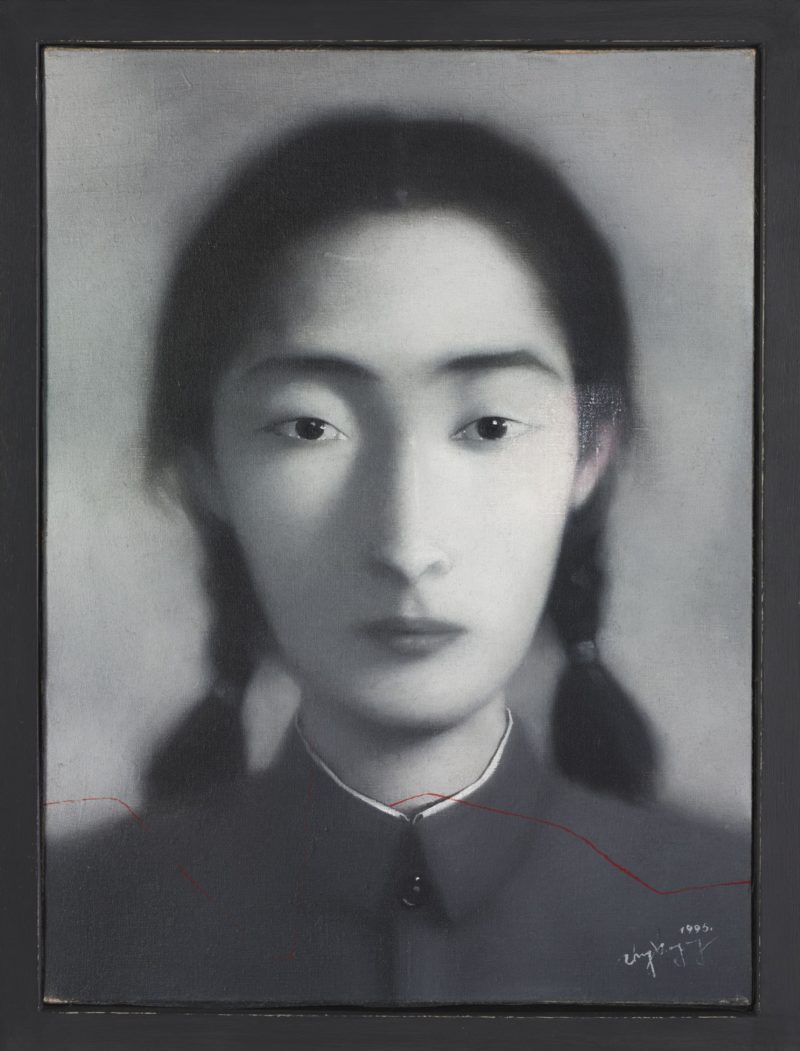

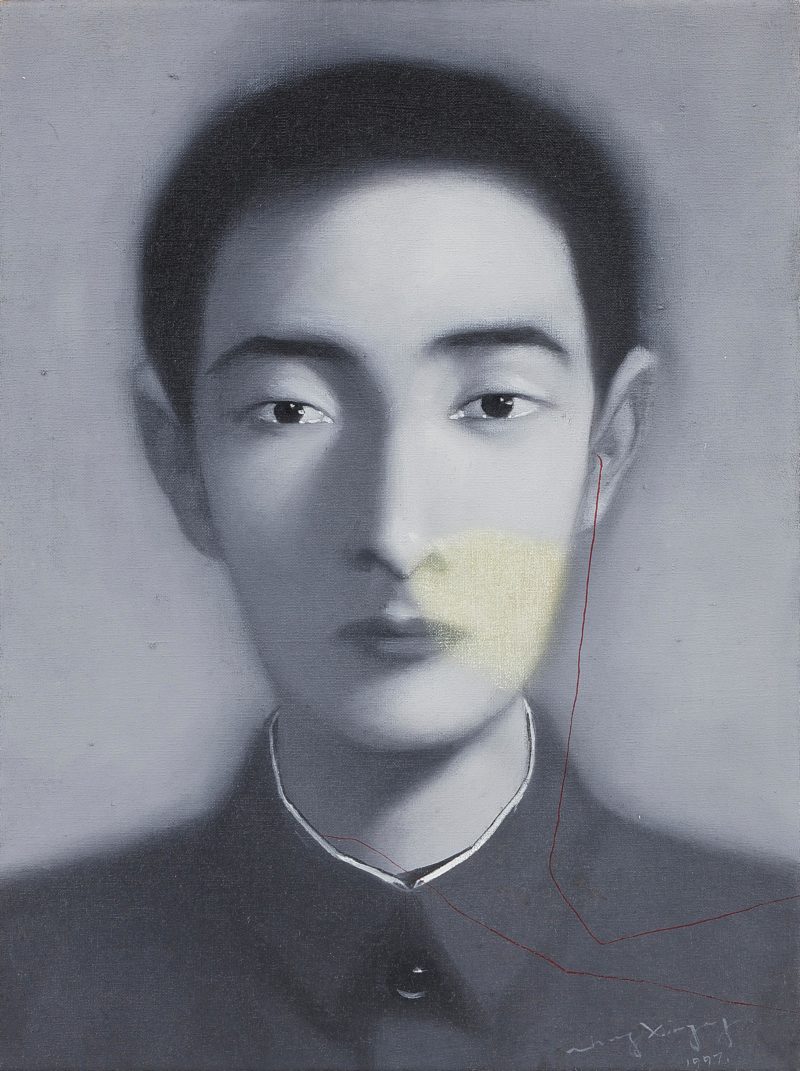

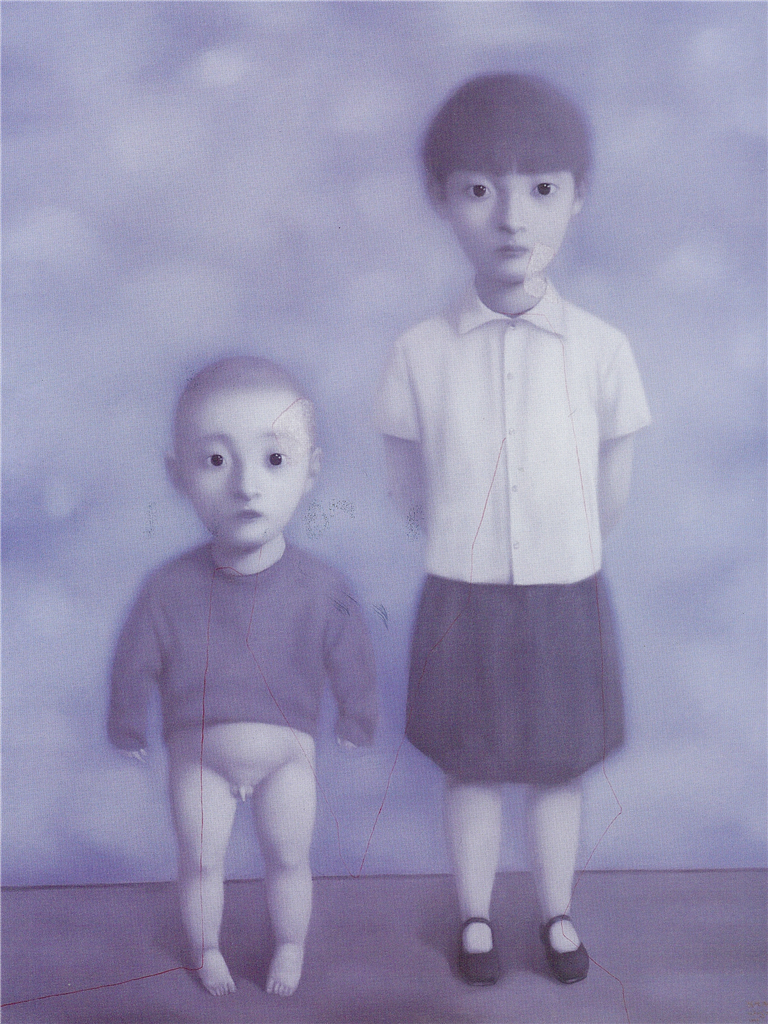

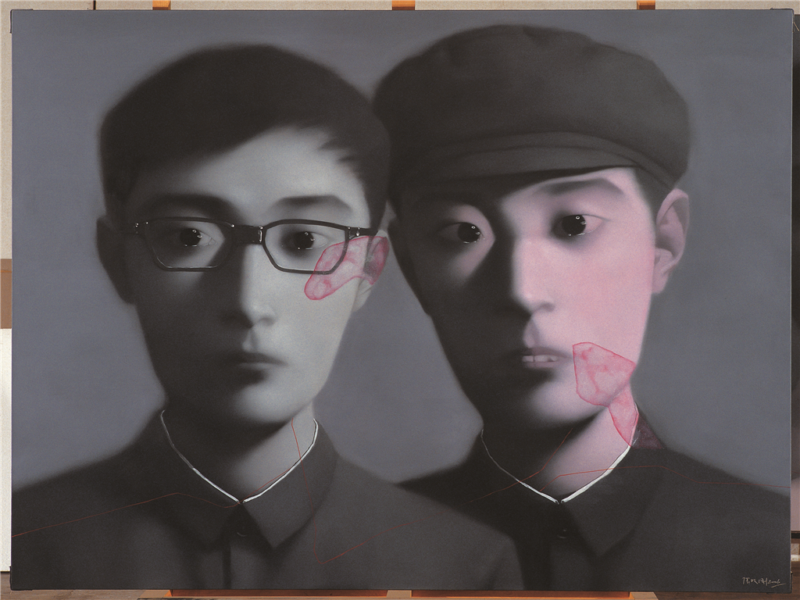

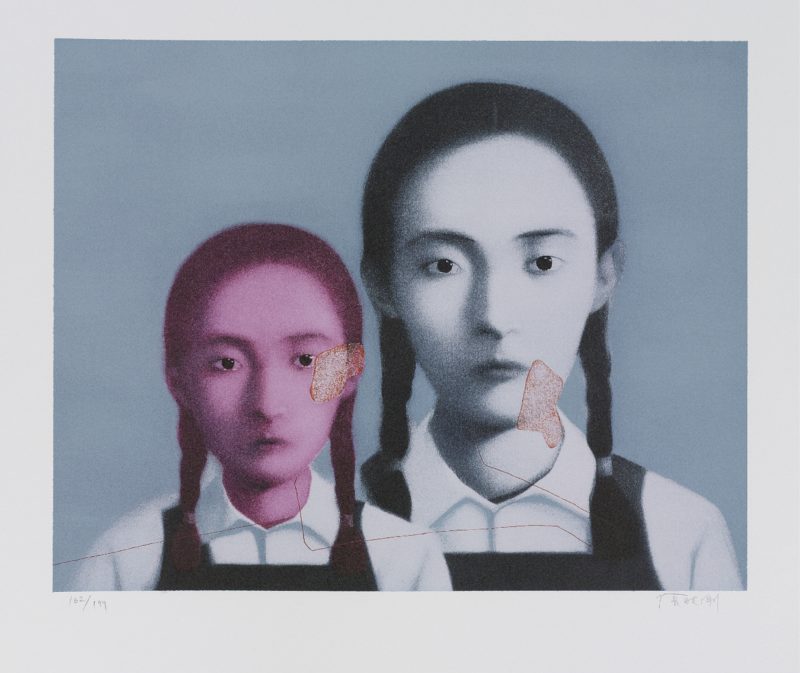

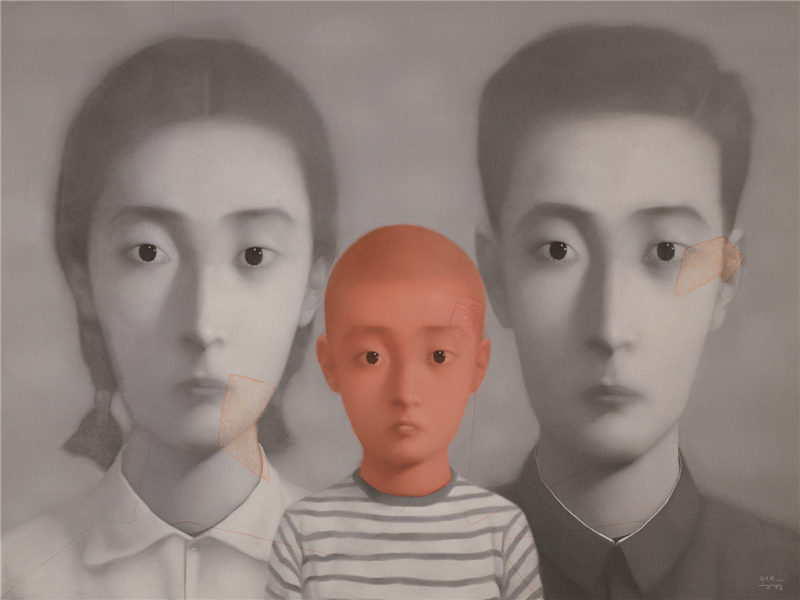

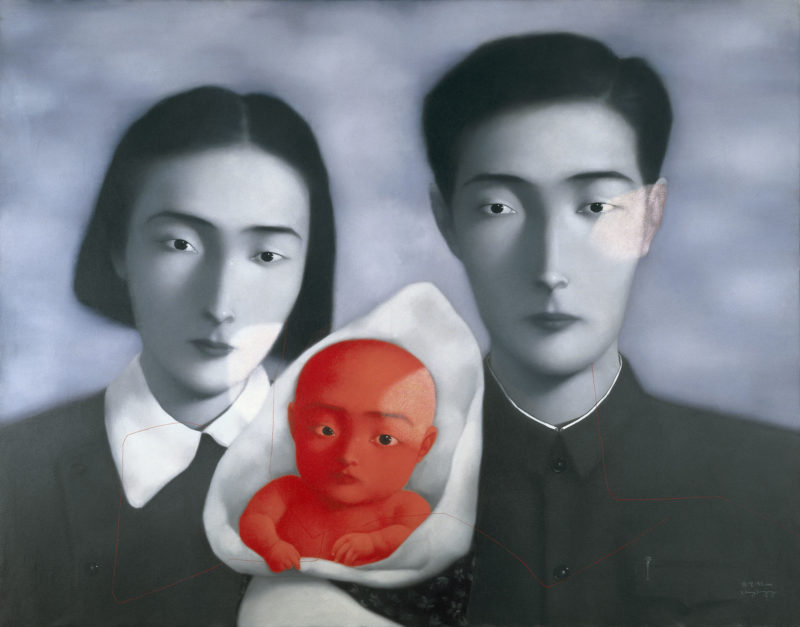

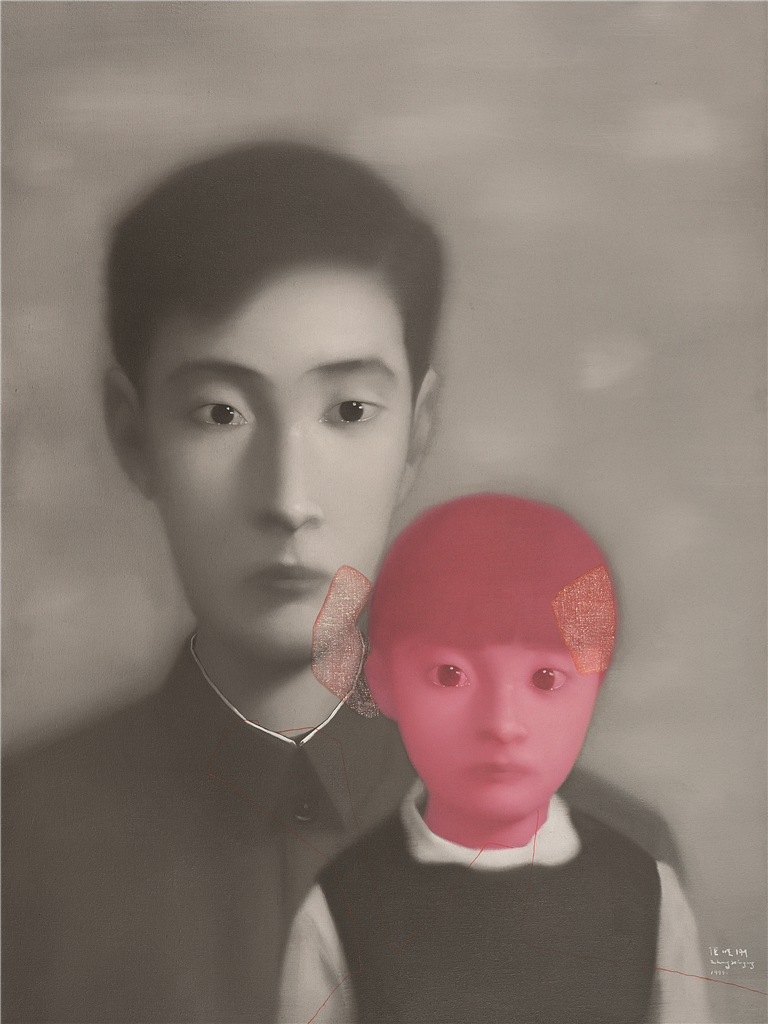

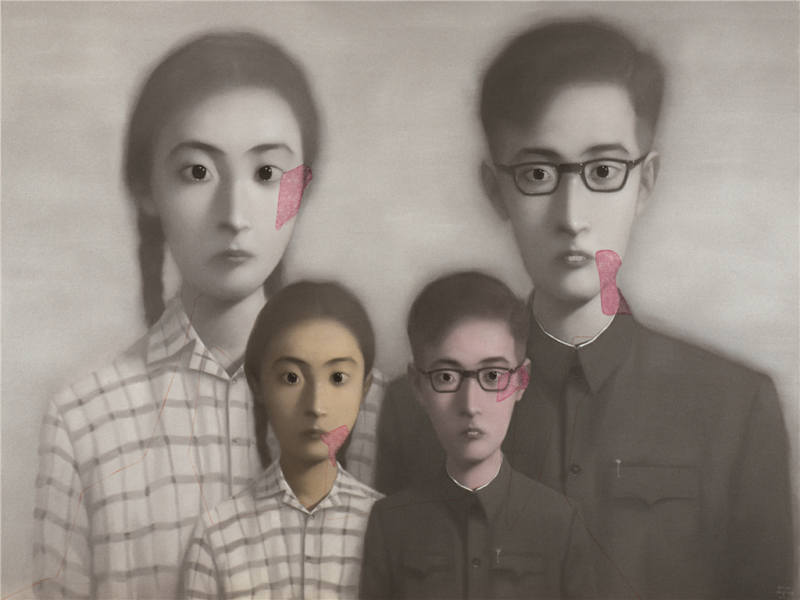

Zhang Xiaogang 1 is a Chinese surrealist and symbolist painter. He is most famous for his Bloodline series, a body of work characterized by predominantly monochromatic portraits of Chinese people. His wide-eyed subjects featured in his stylized portraits of Chinese people are posed stiff and upright, deliberately reminiscent of family portraits from the 1950s and 1960s.

Early childhood

Zhang was born in Kunming in China’s Yunnan province in 1958 and was the third of four brothers. His mother, Qi Ailan, taught Zhang how to draw to preoccupy him to stay out of trouble.

From early on, my parents worried that I would go out and get into trouble. They gave us a paper and crayons so we could draw at home… I gained more and more interest in art. I had a lot of time because I didn’t have to go to school. My interest increased. After I became an adult, I never gave up art. So that is how I started to draw.

Zhang’s parents were taken for re-education for three years by the Chinese government. By the time he becomes matured to understand what was going on, the country was under political unrest. It was during the late 1960s political disturbances historically known as the Cultural Revolution 23. Growing up in this era had a massive influence on Zhang’s painting. Those years witnessed the annihilation of a significant number of historical documents, including family portraits. Family photos were a strong tradition in China before the revolution. The change in the family portraiture tradition represents to many the loss of precious family memories that are addressed in the Bloodline: The big family series.

First paintings

Aged 18, in 1976, Zhang found himself working on a farm courtesy of the “Down to the Countryside Movement 45.” But before going to work on the farm, Zhang received some training from Lin Ling, a Chinese watercolor painter, studying formal watercolor and sketching methods.

It was not after coming of age that Zhang wanted to be an artist. He recalls,

When I was 17, I told myself I wanted to be an artist…I felt that art was like a drug. Once you are addicted, you can’t get rid of it.

In 1977, Zhang joined the Sichuan Academy of Fine arts after China’s government reinstituted the entry examinations in colleges. At the university, he studied oil-based painting. He continued learning about different styles of Revolutionary Realism 67, ideologies established by Mao Zedong 8. But these principles only served to repel Zhang and his peers towards western philosophy.

Depression & Alcoholism

After graduating from college, Zhang hoped to venture into teaching but was denied the chance. The denial affected him so much that he slumped into depression for about three years. Between 1982 and 1985, he worked at construction sites in his home town. Zhang was having difficulties fitting into society, something that led him to self-intense examination. He even became an alcoholic and, as a result, found himself in the hospital with alcohol-induced internal bleeding. This was in 1984.

During his time in the hospital, he started painting the series “The Ghost Between Black and White,” expressing his visions of life and death while in a hospital bed.

Speaking of the experience, Zhang said:

At that time, my inspiration primarily came from the feelings I had at the hospital. When I lay on the bed, on the white bed sheet, I saw many ghost-like patients comforting each other in the cramped hospital wards. When night dawned, groaning sounds rose above the hospital and some of the withering bodies around had gone to waste and were drifting on the brink of death: these deeply stirred my feelings. They were so close to my then life experiences and a lonely, miserable soul.

Art Groups & Teaching & Tiananmen

These experiences changed Zhang for the better. He started to collect the pieces of his life by joining a movement called New Wave 910. The new movement led to the philosophical, artistic, and intellectual explosion of the Chinese culture.

Zhang felt he needed to do more than just joining a movement. Therefore, in 1986, he formed his own art group called South West Art Group 1112. The group included Pan Dehei, Mao Xihui, and Ye Yongqing, a total of more than 80 artists with the same ideologies as Zhang. The collectivist rationalization had suppressed the desires of many people for many years. The main idea of the group was to counter this effect.

However, his dream of becoming a teacher came through in 1988 when he was appointed as a teacher at Sichuan Academy’s Education Department. His life was starting to have meaning. Zhang even got married that year and took part in the China/Avant-Garde Exhibition held in Beijing at the Art Museum of China. However, his quest for liberal reforms was abruptly ended by the Tiananmen Square 1314 incident in 1989. Soldiers opened fire at civilians, presumably leading to thousands of deaths.

Trip to Germany & Return to China

In 1992 Zhang made a trip to Europe, Germany precisely. While staying there, he learned how the Chinese people are viewed outside China, something that changed his expressive and surreal styles massively. Zhang tried hard to learn from western artists by analyzing their works in museums and galleries. He felt like he needed to do more as an artist, especially as a Chinese artist, as there were not many artworks in the western galleries that depicted Chinese culture. He said:

I looked from the ‘early phase’ to the present for a position for myself, but even after this, I still didn’t know who I was. But an idea did emerge clearly: If I continue being an artist, I have to be an artist of ‘China.

After his time in Europe came to an end, he went back to China to put more effort into himself as an artist. He worked at Mao Xuhui’s studio, and his first paintings showed the Tiananmen Square. While working at the studio, Zhang Xiaogang developed a particular interest in the faces of people around him and China in general. He started to go through old photographs from the past he found in his parents’ house. His fascination with faces became a dramatic turning point as far as his career is concerned. He abandoned his painting style once again and started drawing flat pictures.

Bloodline series

What led to Zhang’s Blood Line Series

During the time of self-discovery, he stumbled upon his old family photos that changed his career path.

I felt excited as if a door had opened. I could see a way to paint the contradictions between the individual and the collective, and it was from this that I started to paint. There is a complex relationship between the state and the people that I could express by using the Cultural Revolution. China is like a family, a big family. Everyone has to rely on each other and confront each other. This was the issue I wanted to give attention to and, gradually, it became less and less linked to the Cultural Revolution and more to people’s states of mind.

In the old family photos, Zhang came across a photo of his mother as a beautiful young woman before her health deteriorated. That is how his famous series ‘Bloodline’ came into existence. The series depicted the predicament of private and public life.

Technique

Zhang uses vivid lighting effects combined with flat indistinctive backgrounds to venerate his subjects. In his work, individuals are painted with a smooth pearly finish looking very similar to the finish of porcelain 15, and their faces lack any emotion whatsoever. These detached faces stare into the audience and the world beyond. However, the reminiscence of the traditional family portrait draws you in, contradicting the aversion to the seemingly unnatural expressionless stare of the figures staring back at you.

Popularity & Market success

Soon after releasing, Bloodline received positive coverage and was exhibited worldwide, including countries like the United Kingdom, United States, Australia, France, and Brazil.

Bloodline made Zhang Xiaogang a bestselling Chinese artist and one of the favorites for western collectors. In the early 2000s, the Bloodline: Big Family series was among the must-haves for collectors worldwide. The popularity of the series became a blessing and curse as he was forced to work even harder to meet the demands of his work. In 2014, Bloodline: Big Family No. 3 was sold for a whopping $12.1m 1617.

Speaking about the high demand for his work, Zhang told the South China Morning Post: “I tried doing other things after 1998, but the exhibition demand for the series left me little time. By 2000, I wanted to cut down on my output, but it was very hard after the market took off. It is tough for my generation of artists to say no to patrons.”

While the popularity of Bloodline can be considered a good thing, it has had a severe impact on Zhang’s career. Only a few people paid attention to his other works.

Some commentators say this is because Zhang has over-produced his popular Bloodline series. But Zhang disagrees with that statement:

The events of 1989 (Tiananmen Square massacre) left me in shock. All the western collectors who had supported us no longer had access. There was certainly no state support, and we had to slowly build up relationships with new collectors.

For that reason, when his previous collectors come back alongside others, wanting another version of the Bloodline series, he was obliged to say “yes.” As Zhang explains further, “You can’t very well say, sorry, I don’t need you anymore.”

Video: Interview, 2011

Analysis

Through his painting, Zhang questions concepts of difference, otherness, and perception. His sitters stare out from the canvas with penetrating detachment, thus confronting the audience with an almost otherworldly gaze; the sitter’s vacant expressions seem to look into the audience’s soul. Nothing can escape from their big piercing eyes.

Zhang Xiaogang uses his talent to create a sense of nostalgia in his works by employing the conventions of traditional Chinese photography. Zhang’s works reference his own early experiences, which can only be echoed by his generation. However, they still resonate one way or the other with the modern audience’s life.

Paintings

Single portraits

Siblings

One Child Families

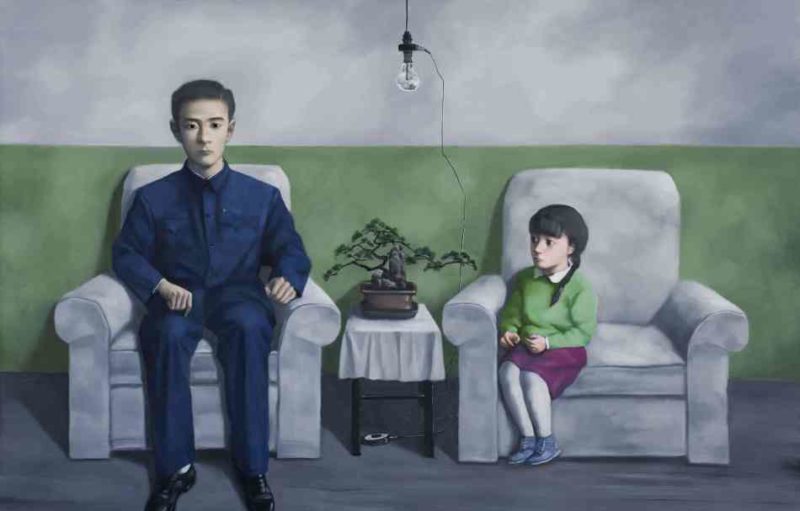

Father & Daughter

Father & Son

Big families

Others

After Bloodline

For the benefit of his artistic skills to grow as well as giving other works space to “shine,” Zhang has actively considered putting the Bloodline series to bed. In 2016, his exhibition at Pace Gallery tried to feature some of Zhang’s new works to draw the attention of the audience to the fact that he has produced many other works other than Bloodline series.

His current works seem to take an entirely different approach from the Bloodline Series. It appears that he is using the theme of silence and storytelling. They tell a story about how shared and private recollections are diffused through family members’ failure to communicate with each other about their painful personal experience.

Paintings

In Bloodline, the sculptures showed family members huddling together against grey against a grey backdrop with shades of a bloodline. Zhang’s new works, such as My Mother (2012), My Father (2012), and White Shirt and Blue Trousers (2012), the family members are divided. One can visibly see the wide gap and sense of “uninterested.” In all the sculptures, a power cord can be seen and appears to be the only common thread separating or linking their lives. The families in the sculptures seem to have a difficult time relating to each other.

My Father, 2012

In the painting My Father (2012) a young girl looks intently at her seemingly uninterested father who is wearing a blue Mao suit 1819. The girl can be seen pining for the warmth of her father. She is even seated at the edge of her chair, showing a willingness to get closer to her father. Between the two is a light bulb hanging from the ceiling. In this case, however, the cord is not a connector; instead, it acts as a divider. The relationship between dad and daughter tells that some emotions are not limited to a culture or a generation.

Sculptures

He recently started to recreate his old motifs from the Bloodline series but three dimensional. Despite the success and effects of Bloodline, Zhang’s most recent works are slowly gaining and resonating with his audience. The sculptures express the need for storytelling among family members and evoke feelings of fundamental human relationships.

Zhang was quoted as saying: “The Bloodline series is like a magical spell that blinds people to them. Nothing else I’ve done has received quite the same level of attention.”