~30min

The story behind Boetti’s Maps of the World

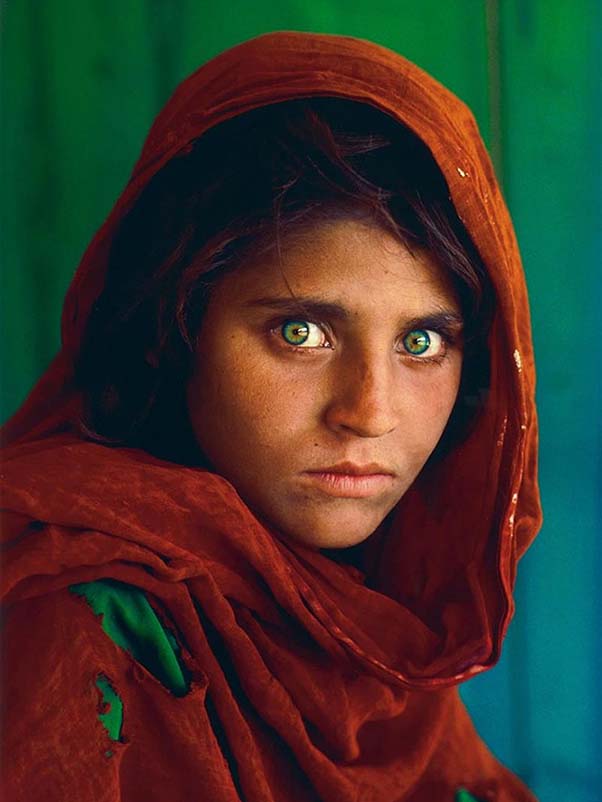

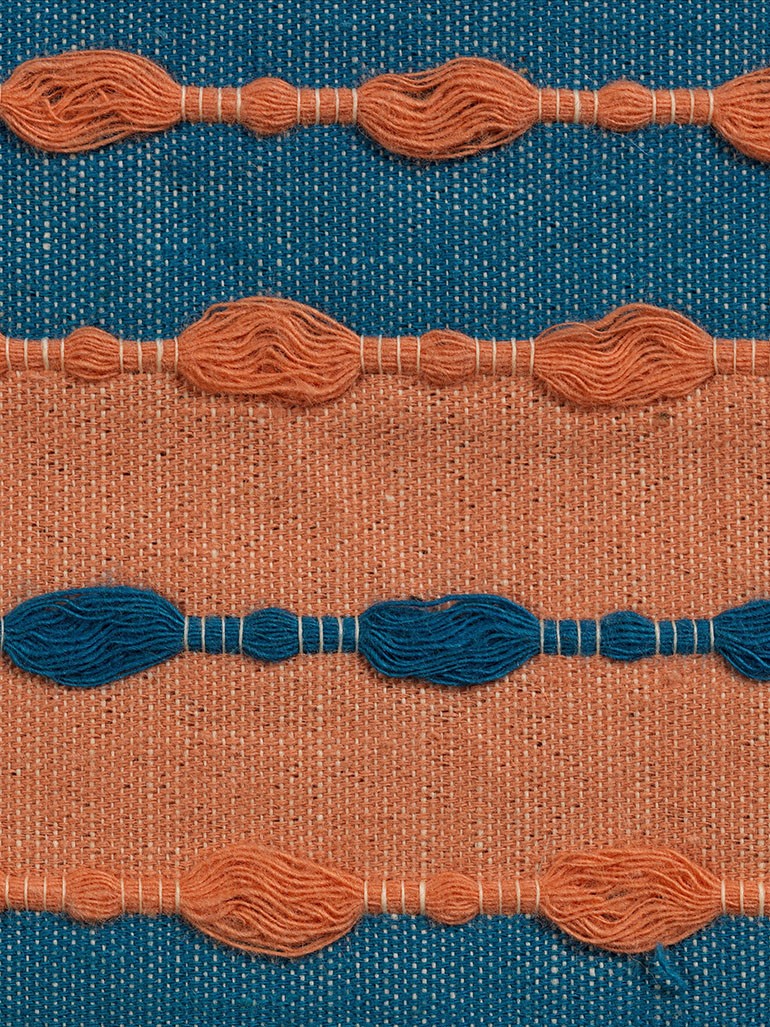

The Mappa tapestries are some of the most important works by Alighiero Boetti 1. Upon his first arrival in Afghanistan in 1971, Boetti began a continuous collaboration with local weavers to produce embroidered tapestries 2, using himself only as the referential artist but considering the works a creation of a combined effort.

Boetti used simple and mostly industrial materials, focusing more on the creative conception of the work and leaving its execution to a team of embroiderers in Afghanistan and later Pakistan. Even though his maps were produced by a team of weavers, Boetti still worked closely with them, which allowed him to address several issues within the practice, such as collaboration, material, and time.

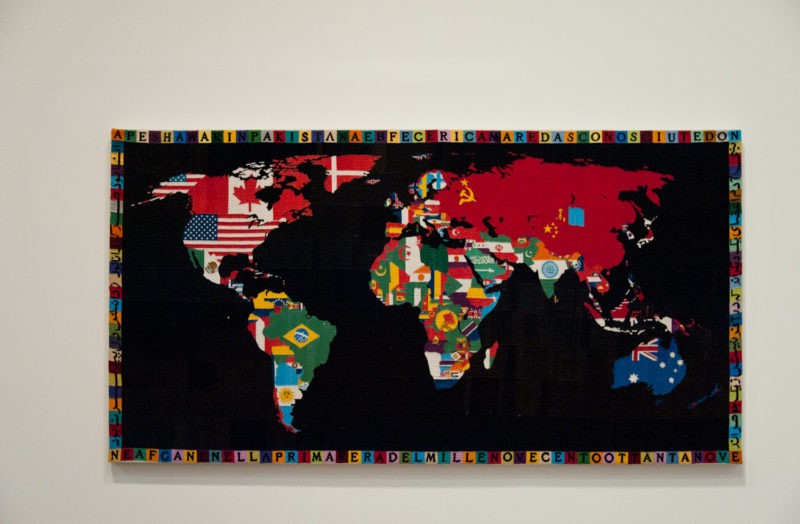

Mappa del Mundo is a colorful, beautifully crafted tapestry showing each country emblazoned with its own flag, examining borders, frontiers, nationalism, and patriotism. The frames are emblazoned with Italian and Persian texts, selected by Boetti and the craftswomen.

It was difficult for Boetti and his team to get it right in terms of the then-current geopolitical condition, with revolutions in Africa, fragmentation in the former Yugoslavia, and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

More than 150 maps created between 1971 to 1994

Boetti traveled to Afghanistan twice a year from 1971 to 1979, when he was prevented by the Soviet occupation. In the 1970s, he established the One Hotel in the capital Kabul along with his friend and business partner Gholam Dastaghir as a type of artistic commune.

Over the next two decades, from 1971 to 1994, more than 150 maps of different colors and sizes were created in this way. Geopolitical changes were tracked throughout the world, transforming a simple idea into a political vision by visualizing territory disputes and regime changes.

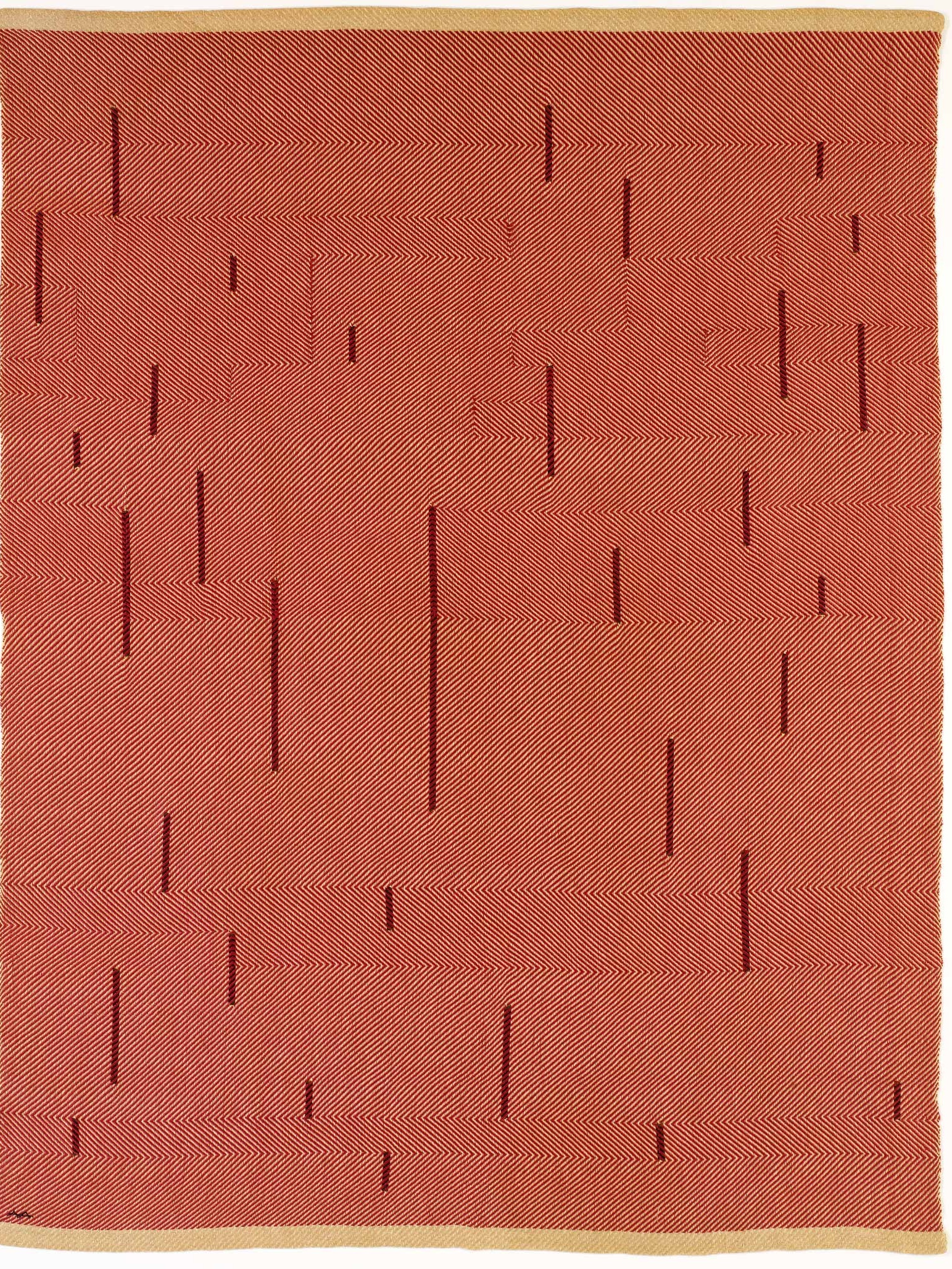

Halfway through their endeavor, the embroiderers selected a pink thread to fill in the oceans, completely altering the look of the works. The show program 34 of his 2012 retrospective at the Tate Modern said:

Boetti loved this intrusion of chance into the design and from then on left it to the makers to choose which color to use for the seas.

Because of this, he had little say in the appearance of the maps. The process of embroidering a Mappa was often lengthy and could take up to two years. Each atlas map would gain a character of transition since the world had dramatically changed since its original design.

The designs for his world maps and his later imagery such as Arazzi 56, were outsourced to as many as 500 women embroiderers, first in Kabul.

Even though the Afghan carpets are known for being different from other Persian rugs, Boetti moved the production of the map tapestries to Peshawar in Pakistan after the Soviet inversion of Afghanistan. However, they were still weaved by Afghans who sought refuge in the town.

This collaboration depicted the artist’s fascination with what it meant to work with people from other cultures. Moreover, it also raised questions about authenticity and authorship in art, which rumbles to this day, with the likes of Damien Hirst 7 and his spot paintings 89, which are almost exclusively executed by employees.

Originality & authenticity in Alighiero Boetti’s maps

The subject of originality is raised frequently in the world of art, but what does it mean in the context of Boetti’s Mappa? The classification of ‘original art’ can be used on any piece of art considered to be the first example of an artist’s work.

For instance, an original artwork would be the first version of a portrait an artist creates, and not their subsequent prints, imitations, or reproductions of the artwork.

A turninng point in Boetti’s career

Alighiero e Boetti was born in Turin, Italy, in 1940. Although not formally trained in art, Boetti was preoccupied with the theory of creativity from an early age. Traveling to Afghanistan at the beginning of the 1970s, he was introduced to the traditional craft of embroidery, which marked a turning point in the artist’s career.

His fundamental concern with the relationship between order and disorder is manifest in his grid structures, derived from the magical squares, that feature sayings and aphorisms that stem from cultural, philosophical, mathematical and linguistic contexts.

First exhibited in 1972

Boetti showed one of his two first embroidery pieces at the section titled Individual Mythologies of the 1972 Kassel documenta 5 1011, curated by Harald Szeemann, the godfather of curating.

His work, exhibited in the section titled Individual Mythologies, was allegedly produced in Afghanistan by a team of women from an “embroidery school” in Kabul, the capital of Aghanistan.

Did Boetti inspire Afghan weavers to create the genre of war rugs?

In the early 1990s, more and more carpets showing world maps combined with military symbols emerged from Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is the Boetti who has often been credited with having triggered the contemporary production of Afghan carpets depicting the world map and even the war carpet genre of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Boetti drew his first colored cartoon flags on a school wall atlas, titled Planisfero politico 1213, 1969, creating the design for his first mappa.

The war carpet style emerged in Afghanistan in the 1980s after the violent occupation of the country by the Soviet Union. Some published accounts, especially that by Luca Cerizza in his book, Alighiero e Boetti: Mappa, Afterall Books, London, 2008, assert that the virtual industry established by Boetti was the stimulus for other forms of innovation in carpet making.

Translating the text in some of the carpets reveals some interesting things. For instance, in one of the atlas carpets, the old Soviet Union is identified as both the “Socialist Soviet Unions of Russia” and the “Federative (sic) Republic of Russia.”

Given that the USSR became the Russian Federation in 1991, this would seem to provide a terminus ante quem, the date before the atlas (and therefore the carpet) could not have been made. This example shows that the atlas carpets of the 1990s came from the kind of atlas/posters found in schools.

Luca Cerizza affirms in his book that nobody before Boetti thought to show us a world like a mosaic tangled with political formations, a puzzle of color and symbols, a muddle of differences, etc. While some researchers credit Boetti with inspiring these works, others don’t agree.

Sergio Poggianella contradicts Cerizza’s views by stating that geographical carpets are centuries older than the maps of Boetti. He says that these geographical carpets were done mainly for the mighty, while in Boetti’s maps, it is for the art market. Sergio Poggianela said the following 1415 concerning Boetti’s maps and their originality:

It would be also very interesting, from the conceptual point of view, to study the artifacts signed by Boetti and the artifacts conceived by the Afghan weavers from an anthropological perspective. Traditional art, when invested by aura, can shift into the contemporary art system, as Boetti, in a masterly manner did, deciding to accept the result of the woven maps, even ordered following a model provided by him, without any other change, any other intervention. We all have an idea of what we mean when we refer to an artist: we think about his [her] ability, inventive capability, aesthetic awareness, inspiration, creative gesture, etc. This can be applied in the artistic environment of any culture, including the afghan weavers’ art, as the art of war or geographical carpets, but only if rules and conventions are [recognized] by the contemporary western art system and art market.

Analysis

One of the main attractions of Boetti’s retrospective Alighieri Boetti: Game Plan, held in 2012 at London’s Tate Modern 16, was a room filled with large textile maps of the world embroidered by Afghanistan and Pakistan weavers.

In these maps, each country is designed with its national flag. Thus the carpets portray geopolitical changes as they occurred from 1971 to 1994, the year of Beotti’s death.

For instance, Afghanistan was left blank in 1983 because of the uncertainty over its sovereignty under Soviet inversion. In 1979, an atlas tapestry was returned from Afghanistan with a pink ocean, signifying the weavers’ inadequate knowledge of traditional maps and the fact that they came from a land-locked country.

Video: Boetti’s trip to Afghanistan in 1974

Other notable exhibitions

He had exhibitions throughout Italy and the United States until his premature death in 1994. Boetti has been honored posthumously with several large-scale exhibitions, most notably at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Vienna in 1997 and the Museum für Moderne Kunst (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) in 1998.

Final words

The collaboration with embroiderers allowed Boetti to infuse Eastern culture and its tradition in his embroideries, closing the gap between West and East. His Mappa series is deeply rooted in a local context while suggesting the world in its entirety.

More by Alighiero Boetti