Hayv Kahraman’s biography

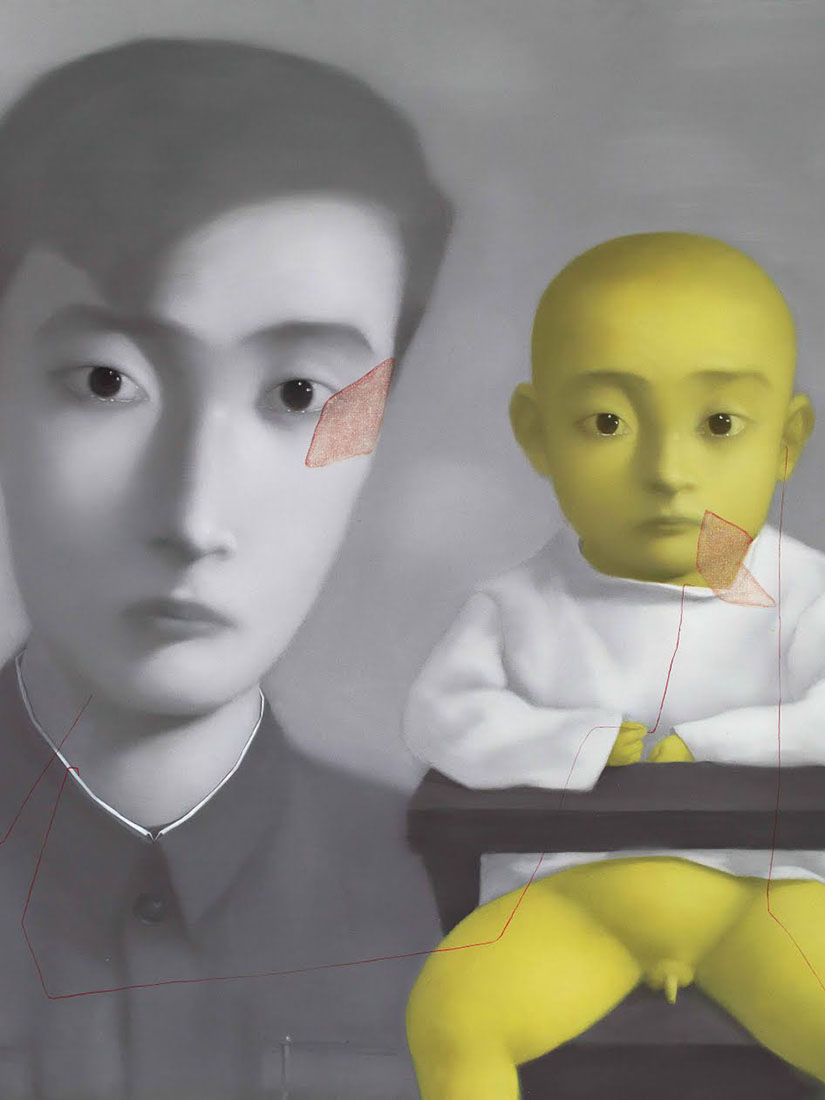

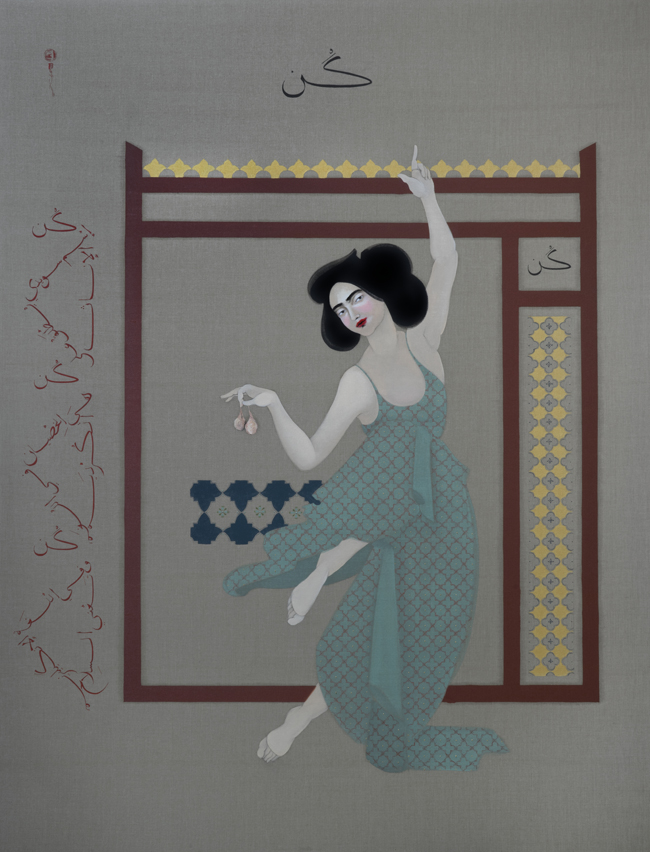

Born in Baghdad, Iraq, Hayv Kahraman 1 is a Los Angeles-based Kurdish-American painter and sculptor known for creating works that reflect controversial 2 subjects such as gender, particularly concerning female identity in relation to her experiences as a refugee and issues affecting her country of birth, Iraq.

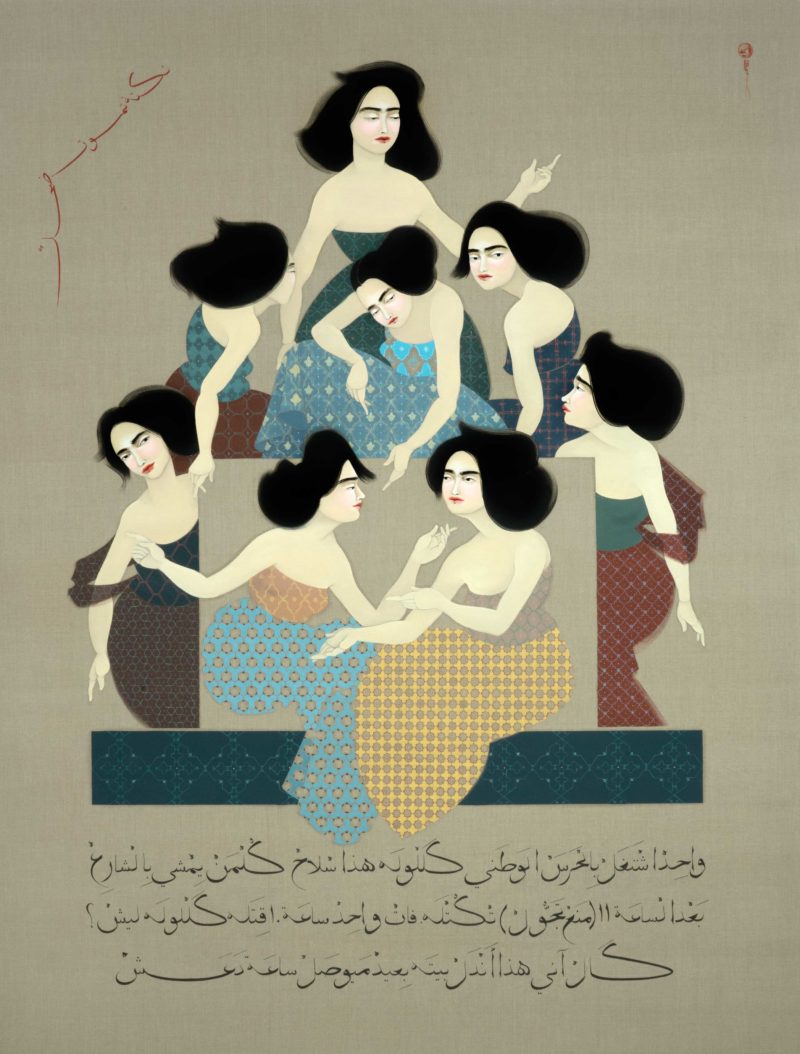

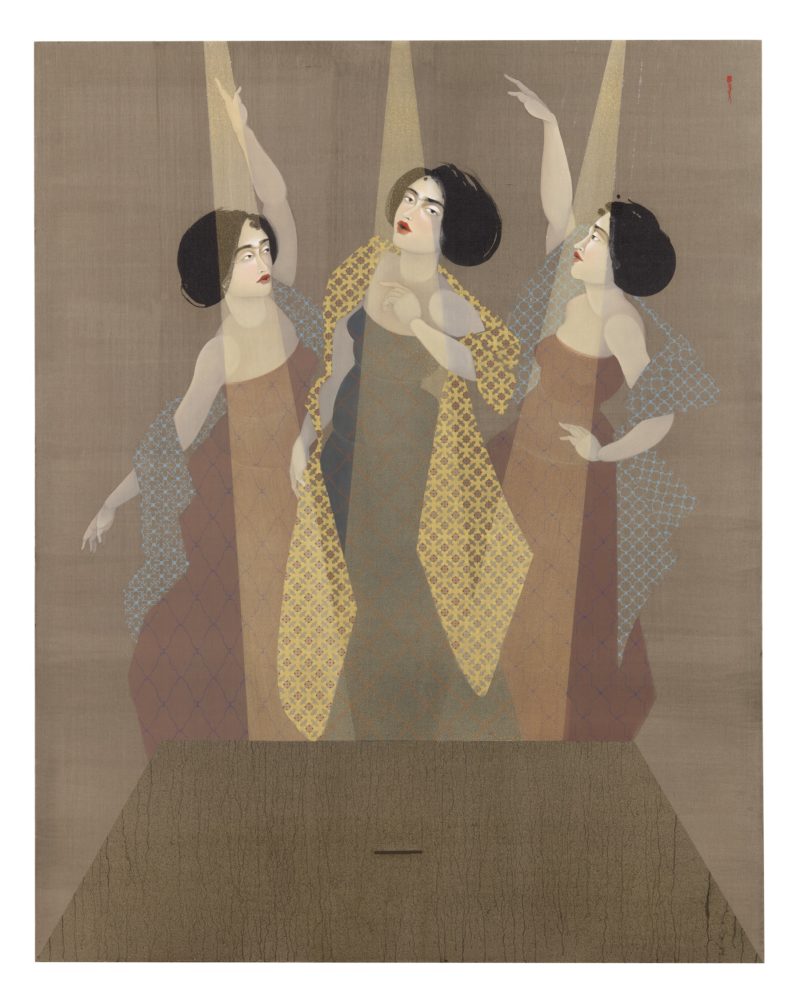

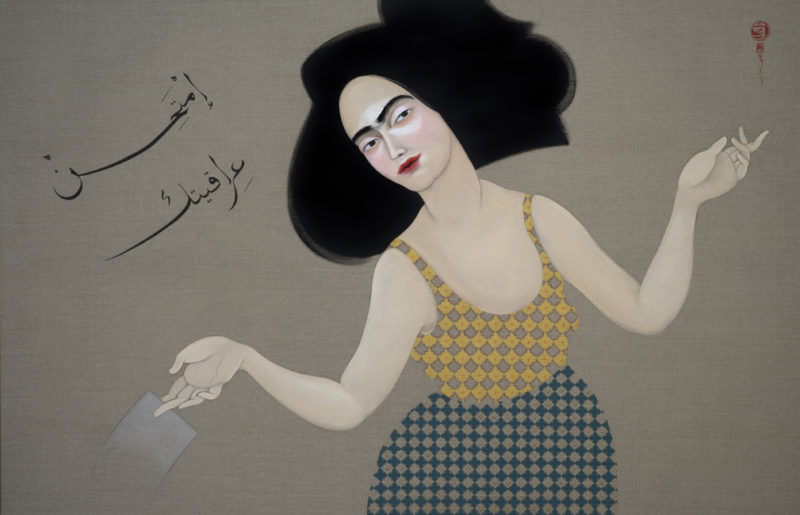

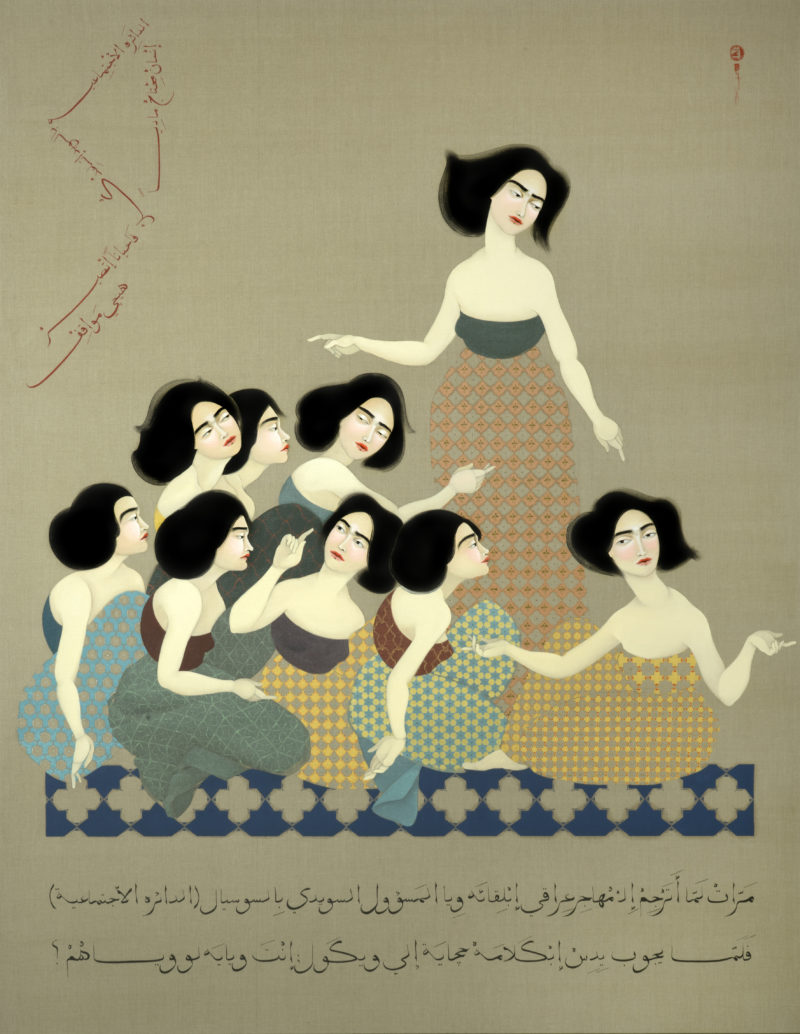

Kahraman’s artwork depicts the impacts of war, significantly the effect on war women. Her diverse stylistic references range from Japanese and Arabic calligraphy 3 Art Nouveau 4, Greek iconography and Persian miniature.

Hayv’s work focuses on the oppression of women within their own culture and the subsequent impacts of their victimization, which lead to even more suffering and anguish in addition to the travails brought about by the never-ending war in Iraq.

While still in Iraq, Kahraman enrolled in the Music and Ballet School in Baghdad, but the ongoing Gulf War meant her family couldn’t stay any longer in the country. Kahraman was just 11 when her family escaped Baghdad to Sweden, where she spent most of her teenage years.

She joined music and ballet classes to continue from where she left but decided to quit due to racism incidents involving her teacher. She started painting at the age of 12 while still in Sweden and even had some successful solo shows before moving to Italy. She moved to Florence to attend the Accademia d’Arte e Design, studying graphic design.

Style & Inspiration

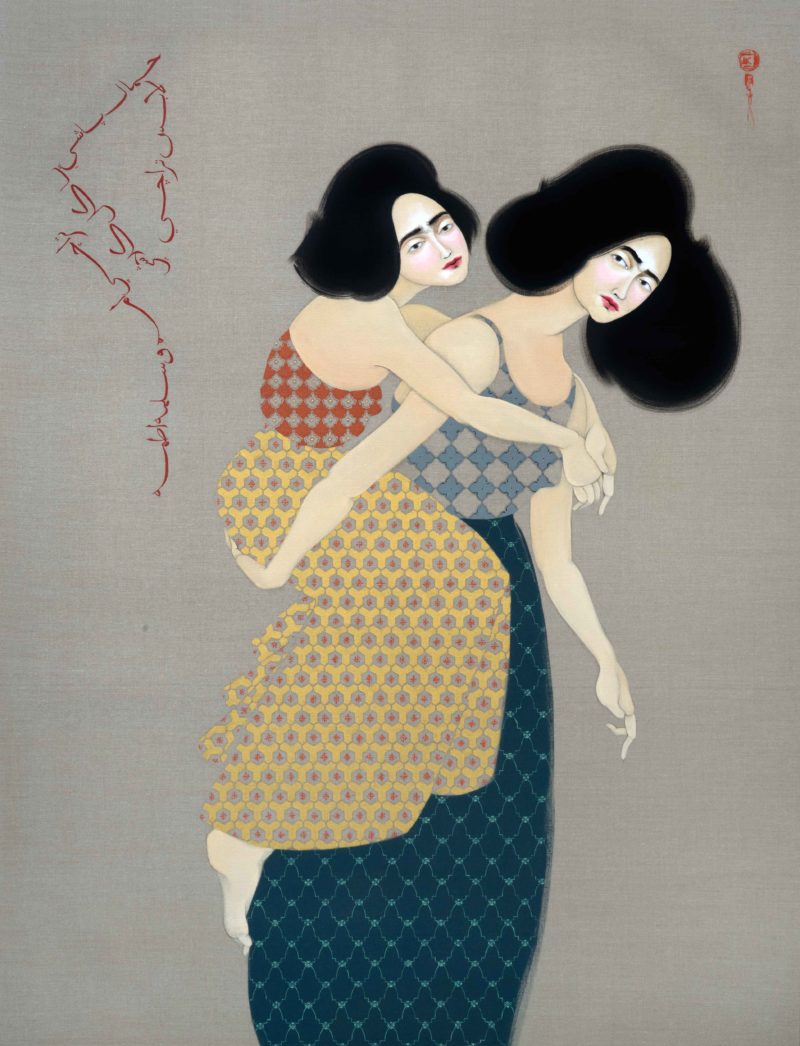

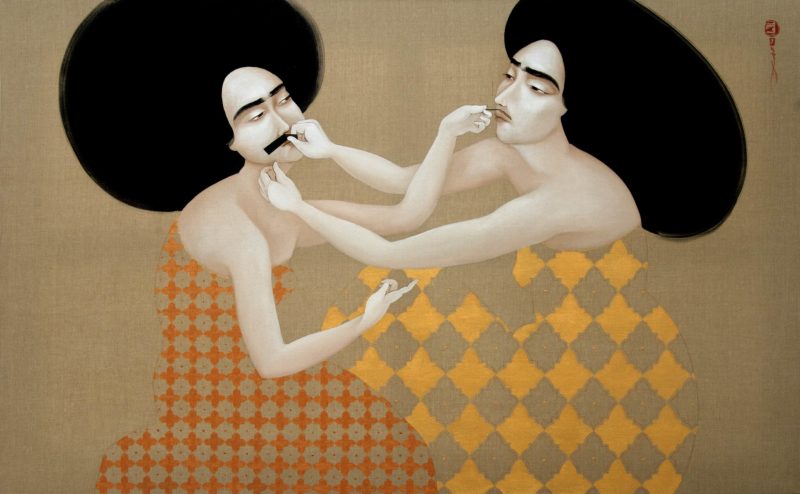

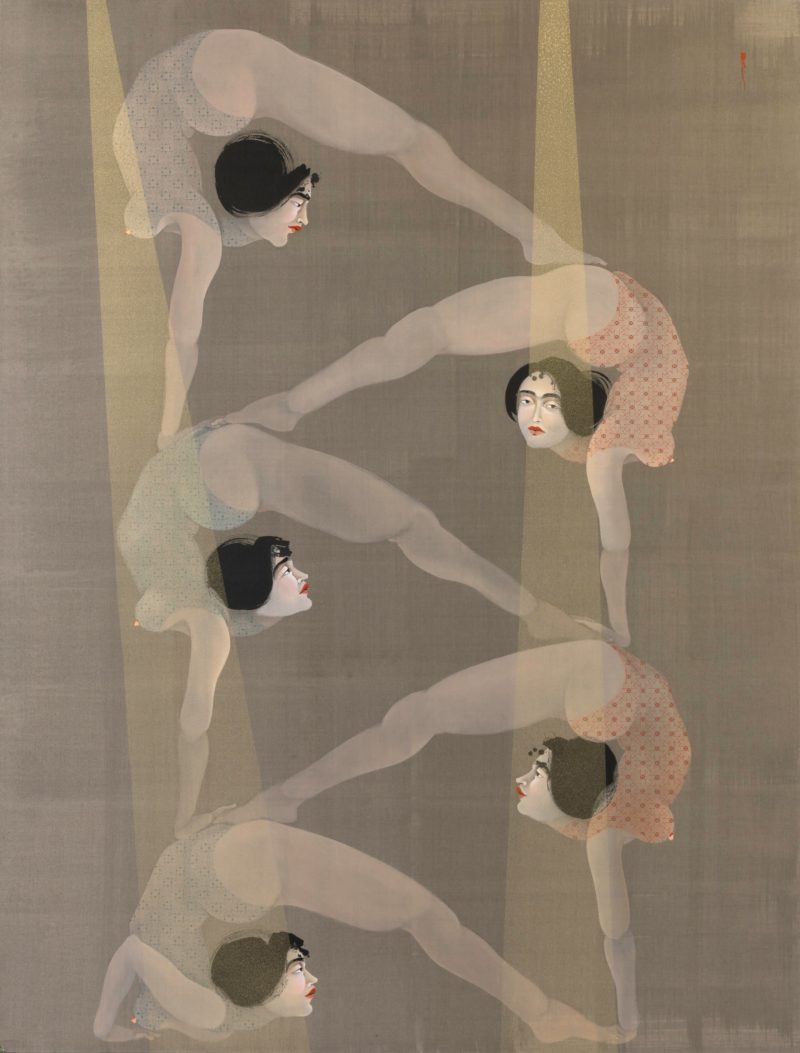

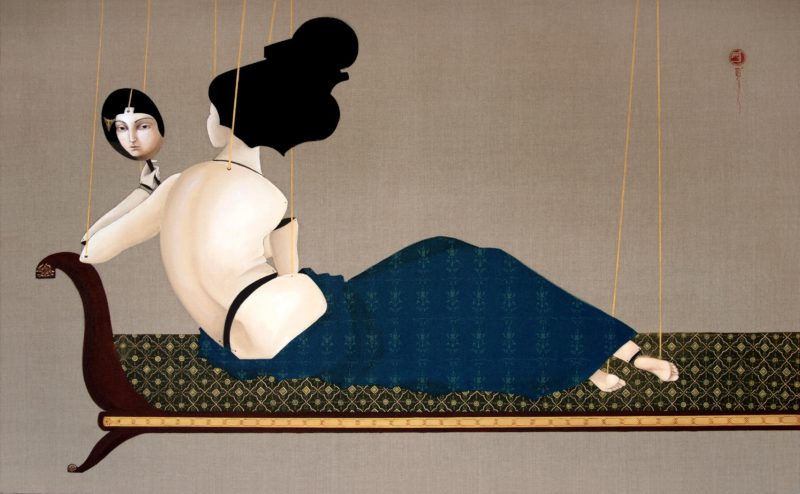

Hayv Kahraman is known for her large paintings of mostly pale women with silk-like skin and soft clouds of dark hair. Having been brought up under harsh circumstances, she often expresses her own experiences in her paintings as an emigrant from Baghdad, Iraq.

Hayv is usually a choreographer of fictional bodies – drawing figures that are an extension of herself. She describes it as follows 56:

I see the figures in my work in choreographic terms. The body, the placement, and the composition are all part of a still snapshot taken from a choreographed movement in my mind.

Her work is contemplative friezes “in which the body takes center stage.”

Kahraman’s paintings serve as a metaphor for how non-white women bend to meet the demands of others, something she herself had to go through while living in Sweden after fleeing Iraq.

Recalling how a dance instructor in Sweden favored white kids and cast her late in rehearsals and training, she said 78, “This fundamental racism is what caused me to quit dancing.”

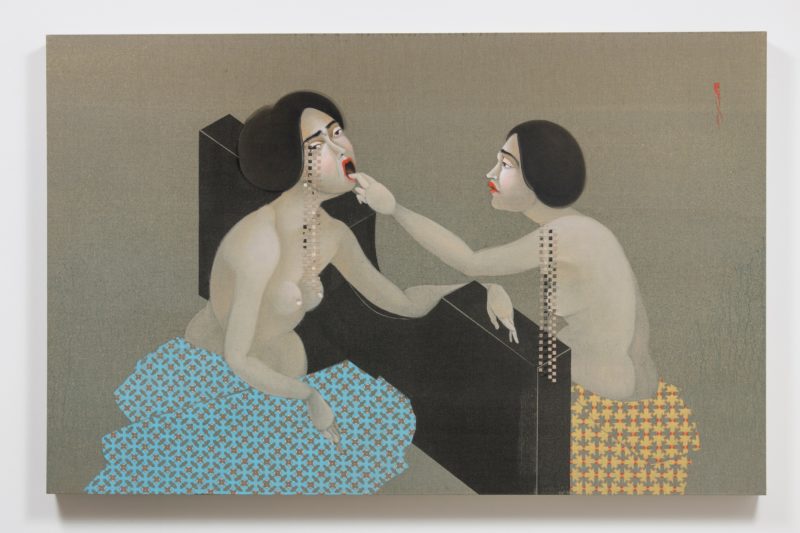

She also survived a physically abusive relationship, which also has influenced some of her paintings.

If you look at my early work, you will notice the women are performing these very overtly violent acts. I remember I had people come to me and say, ‘Why are you painting this violence? What’s going on? Are you Ok?’ And I would say, ‘Yea, of course, I’m fine.’ But it was not until years later where I started looking back and finally realizing and admitting to myself that I was in an abusive relationship at the time, and this was an outlet for me to speak out.

But Kahraman does not only draw from her own experience in all of her paintings. She would also get inspired by what is going on around her.

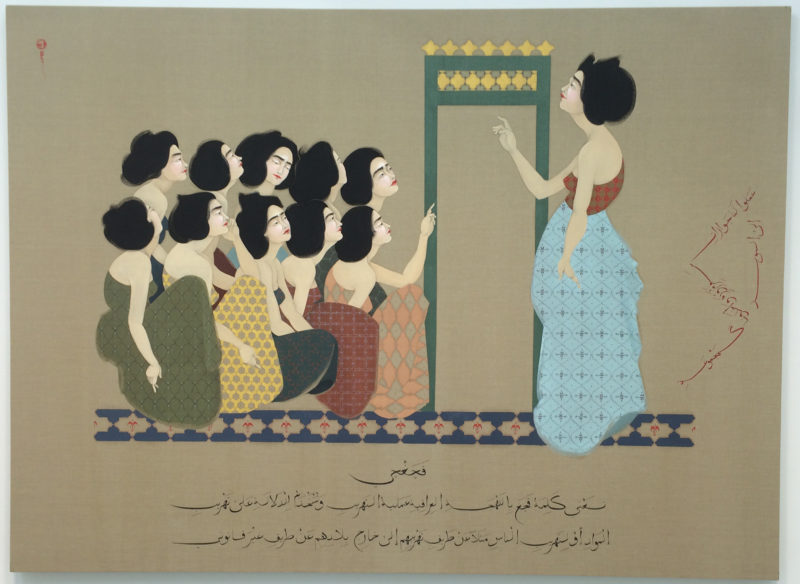

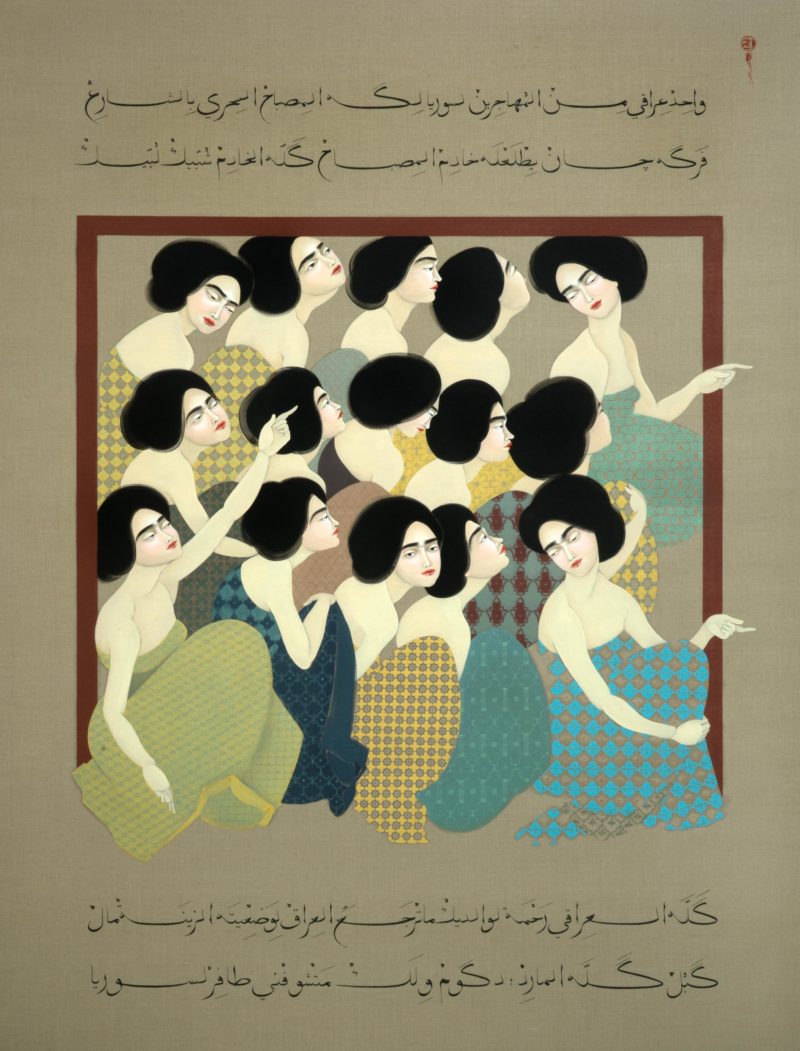

Kahraman is also known for using the Maqamat al Hariri, one of the most prolific examples of the process in Arabic literature, and “the process of writing the text into the works” and transforming them into performative.

Her process is very calculated and thought out. Despite the subject matter, the images contained in most of Kahraman’s paintings display unique feelings of lucidity and control, and her background in graphic design can be seen. Structural and symmetrical logic gives form and function a new meaning, containing and moving past these conflicts.

She says her work is semi-autobiographical – large-scale 11 paintings and sculptures, which in addition to focusing on women, refugees, and migrants, references to the Iraqi architectural design, Italian Renaissance, and Japanese woodcuts.

Her work also uses repetition, a style that was so successful with the likes of Damien Hirst 12, Yayoi Kusama 13, Andy Warhol 14 and Keith Haring 15. Speaking about her use of repeating images of women, the artist said 1617:

I see them as a collective of women. I feel almost like I’m building an army of fierce women.

How being an immigrant influenced her work

Hayv Kahraman’s work contends with the marginal spaces between Western and Middle Eastern culture, including the physical traits and the concepts of gender through her individual histories as an Iraqi immigrant to Europe then to the United States.

Her work has intertextual notes of the Western and Middle Eastern art histories, but her personal aesthetic, as an immigrant, is of her very own and belongs to neither.

Who are the pale women in her paintings?

Hayv Kahraman’s second solo show at Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, called “How Iraqi Are You?” is a grabbing expedition, building on the refined figuration of Persian miniatures.

Her paintings depict pairs and groups of similar-looking women in conversation, with pale skin, large gestures and features that are reminiscent of the women featured in Renaissance paintings combined with the features of the stunning powdered geishas on Japanese woodblock.

The scenes in Hayv Kahraman’s works are actually those from Ms. Kahraman’s childhood, where she grew up in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and later in Sweden. The images depict a sense of styles that have been reborn in addition to the emotions of female empowerment, strength, and intimacy.

Video: Hayv Kahraman: Gendering Memories of Iraq

Video: Hayv Kahraman’s poetry

Exhibitions

Kahraman now lives and works in Los Angeles. Her work has been featured in exhibitions including at several renowned venues, including the Nelson-Atkins Museum (Kansas City); Victoria and Albert Museum (London); Paul Robeson Center for the Arts (Princeton).

Her work is also included in several public collections, including the American Embassy, Baghdad; The Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah; MATHAF Museum of Modern Art, Doha; and The Rubell Family Collection 18, in Miami.

Waraq (2013)

Drawing from her experience as an immigrant, growing up in Baghdad then moving to Sweden, Italy, and then the United States, Waraq is a series that highlights the lives of a group of people who characterize the Iraqi Diaspora, their experiences back in Iraq as well as their struggles and discoveries in their new countries.

Waraq is an Arabic term that means “paper cards”, which references a popular activity Kahraman encountered more often in the daily afternoons of most Iraqis before she and many others left their home country.

The stories of their alienation, assimilation, and discovery are illustrated in ten paintings, along with a large installation structured using the imagery of a recently invented set of cards. Each artwork on the series is reduced and reproduced in familiar images that feature the artist’s reinventions of the cards.

The cards were then sewn with white strands into an 18-foot hanging installation, called Project Al Malwiya. Project Al-Malwiya resembles an upside-down version of a 19th-century spiraling turret, the Al-Malwiya tower, which is 52 meters tall, the same as the number of cards in a complete deck.

The Al-Malwiya tower has significant cultural importance to the Iraqis. It is regarded as a cultural monument, which is now partially destroyed by the cycles of war and internal fights that have impacted the quality of life of the people for the last 18 years.

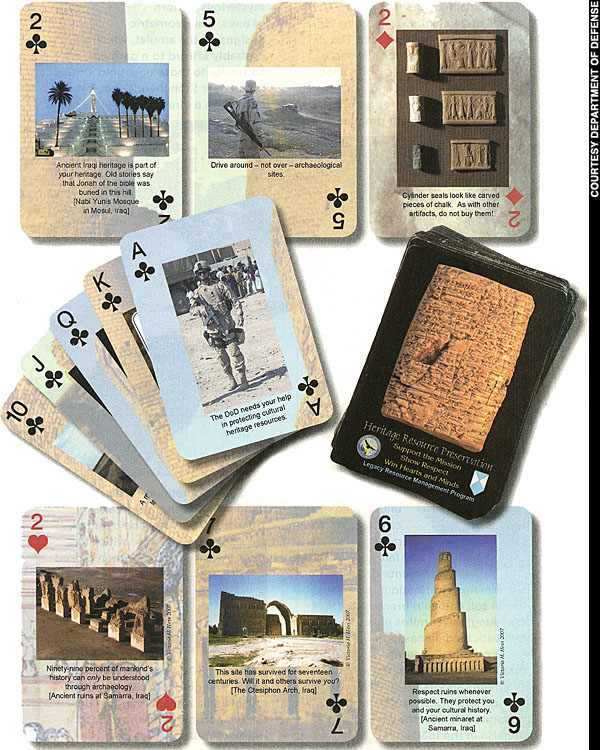

This installation also references “Archaeology awareness playing cards 19“20, which involves 40,000 decks that were printed and sent to the American troops in Afghanistan and Iraq in 2007.

The cards were designed to create awareness on the American soldiers about the damage they cause to cultural sites in Iraq and Afghanistan and discourage the illegal trade in artifacts.

Acts of Reparation (2017)

This installation was displayed in a solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum (CAM) 2122 in St. Louis between September 8 and December 2017. It highlighted the evolution of Kahraman’s artistic style, where the subject, a female body, was pictured in different activities and sequences.

It was also inspired by her tribulations as an immigrant. However, in this collection of paintings, she focused on the multitude instead of the self.

Kahraman describes here female subject 2324 in the paintings as follows:

She is one who dwells in the margins, surviving and navigating a life of spatial and temporal displacement. She is at once an agent of both personal and collective memorial transmission and an interrogator of future and present realities.

The collection of artworks from this exhibition spanned various works from 2011 to 2017, all of which offered insights into the concept of migrant consciousness, resulting in an infinity process of mending.

Her subjects, who often appear in transitional, exist within both conceptual and physical frames. Both subjects and objects address fundamental issues such as diasporic consciousness, collective memory, gender politics, and violent uprooting.

These themes further appear in another body of work titled “Icosaherdal Body”, a sculpture based on a 3D rendering of Kahraman’s own body scan. In this sculptural work, the artist offers an emotional perspective of what diasporic disembodiment means.

This series also includes Concealed Weapon, which highlights the notion of repair. In this work, the linen has been surgically pierced to resemble an act of revolt.

These calculated cuts and wounds were enabling the painting to breathe. Letting air pulsate through the surface from the front to the back and the front again, inhaling and exhaling, it was reacting, resisting, and defending.

Re-Weaving Migrant Inscriptions

Staged at Jack Shainman Gallery, Re-Weaving Migrant Inscriptions was Kahraman’s third solo show. It focused on the mahaffa as an object of aide-mémoire value.

The mahaffa is a hand-held fan created by weaving 27 the fronds of palm trees from the Sumerian and Abbasid eras. It is still made in Iraq today the same way it was back in the days. But most importantly, the mahaffa is one of the only few objects Kahraman’s family took while fleeing Baghdad during the first Gulf War.

Here 2829, the artist describes the mahaffa and how she weaves her canvas:

I remember my mom walking into the room and placing a medium-sized suitcase on the floor and saying, ‘It’s time.’ We could only bring one suitcase. We packed the necessities for survival. But we also packed a mahaffa. It traveled with us through the Middle East, Africa, and Europe until we finally reached our destination in Stockholm. It now decorates our home in Sweden. Assuming qualities of a shrine or memorial as it carries past imaginations of ‘home,’ both idealized and contested.

Speaking about the process of weaving her canvas, Kahraman says 3031:

There’s a sense of betrayal and resolution as I weave the strips of one shredded figurative painting into another’s torn surface. The process is palimpsestic in nature, yet you can still see and feel the painting’s original layer. It is not restored to its original state. It is transformed. The final work is a synthesis of transversed materials and bodies each carrying their own mnemonic itineraries. There’s a catharsis that happens during the act of weaving as I surgically cut the substrate and then attempt to repair it. The body, Her body, is a sight where trauma resides and in that violence, there is rebirth. Perhaps this comes with the territory of being a refugee, an endless activity of collecting fragments and repetitively weaving them into our memories, both as a form of mourning trauma but also as a drive to circumvent erasure.

For me, however, the questions remain: How do these objects function within the psyche of a refugee? What does it mean to suture fragments in the effort to archive them, and why is this important?

Silence is Gold

Beauty and anguish continued to domain Kahraman’s paintings in Silence is Gold. This body of work constituted her first solo exhibition in Los Angeles and comprised an impressive 32 canvases varying in scale from the intimate to the expansive.

Predominantly oil linen, most of the paintings in this exhibition employ a weaving technique used in mahaffa. In these artworks, the artist reproduced the woven touch by cutting into the fine-linen canvases, weaving in offcuts of other paintings, at the same time harming and mending the artwork, both metaphorically and literally.

This references her past traumas and the transformations she has since made in her life. Each painting depicts a female contorting her body into various gestures while holding a mahaffa.

Kahraman’s paintings, according to anthropologist Miriam Ticktin 3233:

Echo Orientalist fantasies in places like colonial Algeria, documented in old colonial postcards, where women were featured as oppressed and imprisoned in harms, and yet their largely fictional entrapment actually serves as a sexual fantasy for the West.

At the closing reception of the show, Us and Them brought actual female performers into the gallery space, consisting of dancers from The Sharon Disney Lund School of Dance at CalArts, with vocal music and composition by CalArts faculty Jessika Kenney and Ariel Ostwerweis. This performance added an extra layer of richness to Kahraman’s work.

Final words

Hayv Kahraman’s body of work suggests several journeys. The first journey involves fleeing Baghdad to Stockholm, Sweden, during the first Gulf War in 1991.

The second journey involves her moving to Italy from Sweden to Study and the third one involves her moving to the United States, where she currently resides.

Layer upon layer of experiences reveals on her canvas. In all of her variegated journeys, Kahraman carried with her an archive of her personal memories, some of which were still fresh while others had been smashed and needed to be unfolded.