Introduction

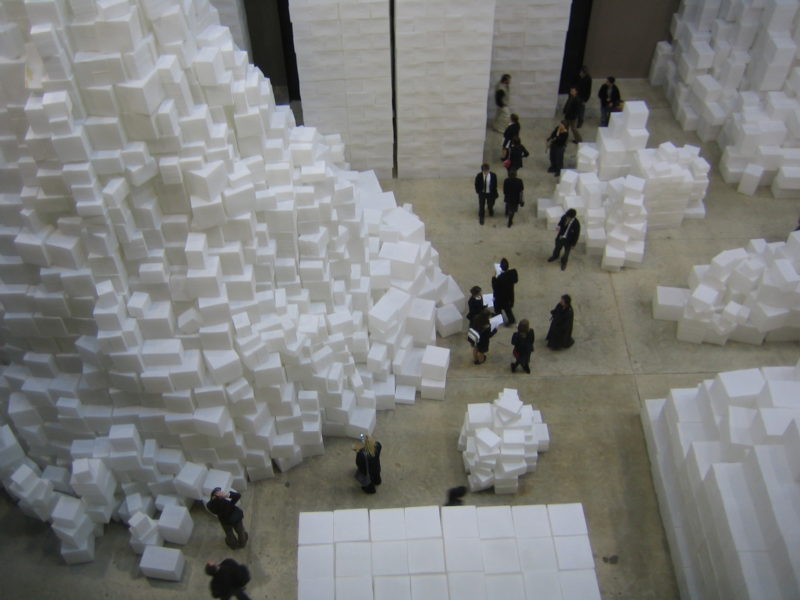

Rachel Whiteread’s 1 installation Embankment stands out for many reasons. First, it’s the embodiment of several ideas. One who looks at it casually would conclude that it represents an obsession with boxes.

Other than that, the combination of arctic icebergs, pristine crystal-clear massive causeway, and sugar-lump village all give it a distinct look that’s almost impossible to find elsewhere. Here, we offer an in-depth review of the white cubes at the Turbine Mall 2 at Tate Modern 3.

How it started

The idea for Embankment started in early childhood. Without the old, used cardboard box, Whiteread might never have found the initial inspiration for the white cubes. She came across the box just after her mother died. While going through her mother’s belongings, she found the box.

With time, the box’s sides began falling apart. Eventually, its lid shone bright with the remnants of the Sellotape used for binding it up repeatedly over the years. Based on this, you begin seeing where Whiteread’s ideas for Embankment emanated.

Old container inspired Whiteread

For years, Rachel Whiteread found inspiration for her artwork from old containers. She would feel inspired to create upon seeing and studying worn containers of various sizes. For example, Whiteread created life-size cast representing the interior of a terraced house that had been condemned in East End, London 45.

Ultimately, that cast convinced judges to award her the 1993 Turner Prize 6. Seven years later, she created the Holocaust Memorial in Judenplatz, Vienna. That 2000 cast featured an entire library.

Other than that, Whiteread relies mostly on spaces that indicate or carry hints of human life. In this regard, you would mostly see her works revolving around ideas representing human life. Additionally, her artworks would also feature monuments around which humans live.

You wouldn’t be surprised to learn that she looks at bodies representing human life too. In all these, what comes out clearly is the source of her inspiration. Consequently, we all have the old containers to thank for inspiring her installation at the Tate.

The uniqueness of Embankment

Embankment wasn’t the result of only one source of inspiration. Instead, it is the result of several different inspirations. As already established, she got the idea for the bigger picture from her old container.

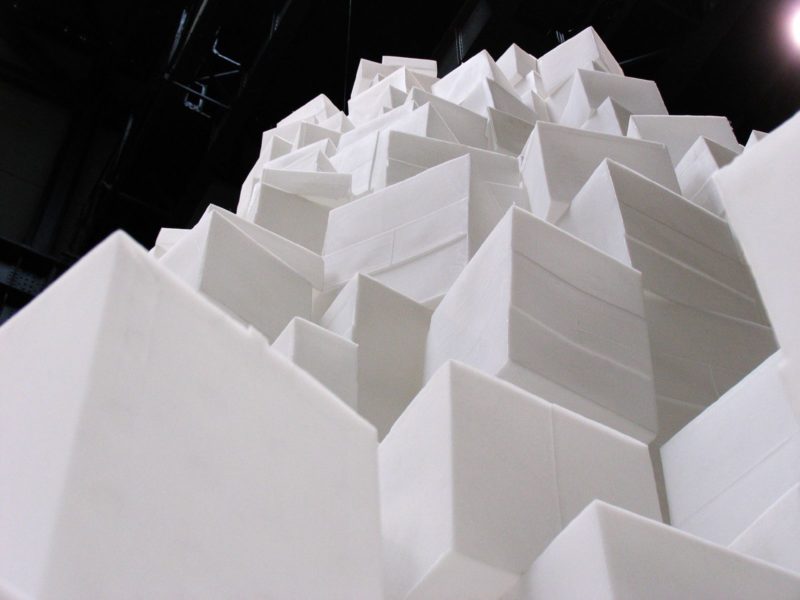

However, as seen with the Turbine Hall’s installation, multiple boxes with various kinds of shapes also contributed massively to the creation of Embankment. Whiteread filled the boxes with plaster. After that, she peeled the exteriors away to remain with nothing but the best casts.

Conclusion

Looking at Embankment, one might be forgiven for seeing icebergs. However, what you see aren’t icebergs. Rather, they are old boxes. She re-fabricated those boxes in translucent polyethylene. More importantly, she did this for and with thousands of boxes.

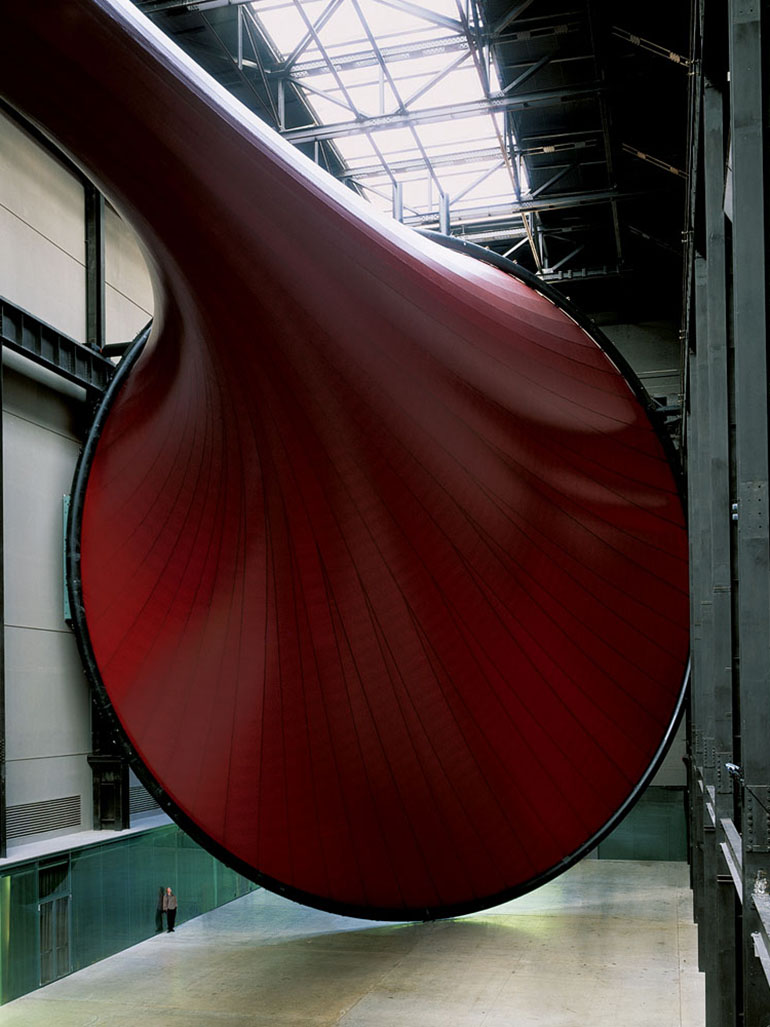

Turbine Hall also features hints of a warehouse. For this reason, it’s easy to see why some people might see space that has transitioned from industrial to a museum. As a final thought, Embankment’s reference to American minimalism 7 is also not in dispute.