Permanently closed

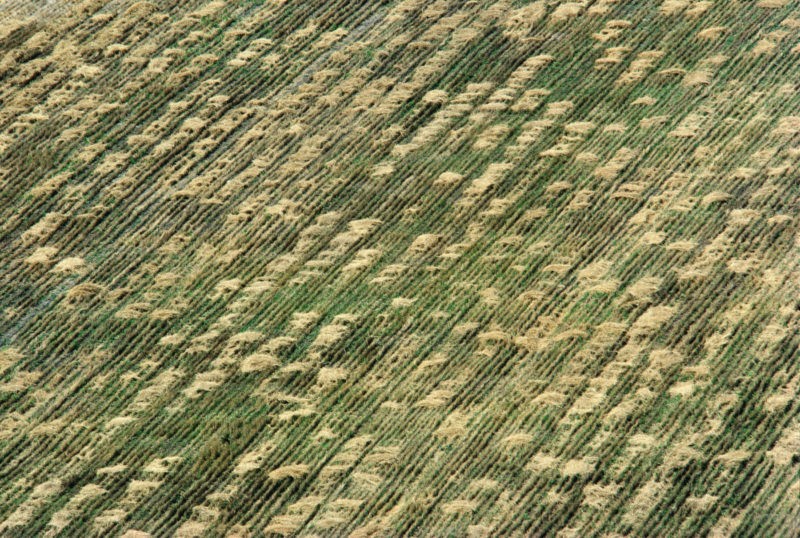

This temporary artwork was planted in the spring of 1982 and harvested in the summer of the same year.

The wheatfield was removed shortly after the harvest as part of the planned closure of the installation.

Wheatfield – A Confrontation

Agnes Denes is a renowned Hungary-American and artist with numerous pioneering artworks that carried a prophetic message. She is known for her groundbreaking use of metallic inks and other non-traditional materials in creating an unusual body of exquisitely rendered prints and drawings that delineate her explorations in philosophy, mathematics, science, geography, and other disciplines.

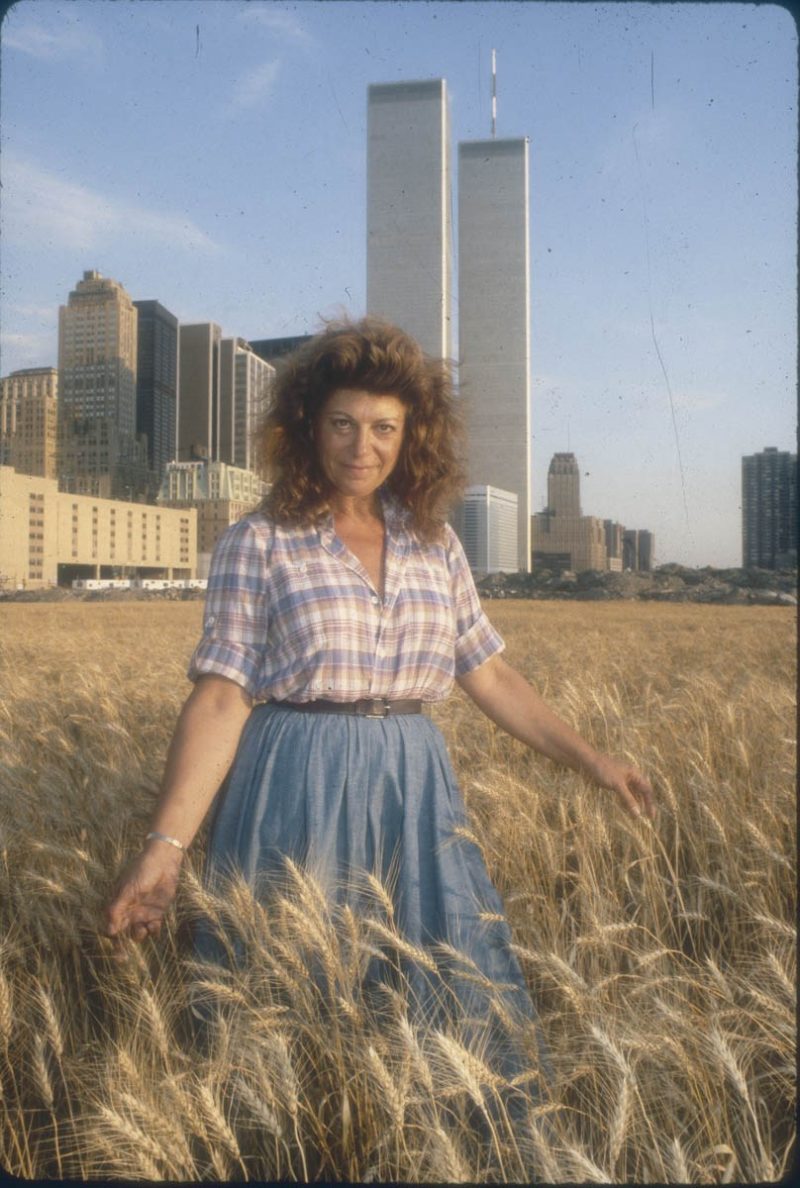

In the act of protest against global warming 1 and economic inequality, she planted an expansive wheatfield in a landfill created after the construction of the Twin Towers, in downtown Manhattan, in 1982.

The field stretched two acres and was planted and harvested by the artist herself in the summer of 1982. It is planting a field of wheat on a property worth $4.5 billion created a powerful irony. The field referred to mismanagement, waste, ecological concerns, and world hunger 2. The act drew attention to the world’s misplaced priorities.

Denes deliberately selected the location due to its proximity to Wall Street, a financial hub and home of the stock exchange where goods such as wheat are traded. This concurrently referenced the economy of the world as well as the state of the earth itself.

Speaking about the work, Agnes Denes said 34:

Making art today is synonymous with assuming responsibility for our fellow humans. We are the first species that has the ability to consciously alter its evolution, even put an end to its existence. We have gotten hold of our destiny, and our impact on earth is astounding. Because of our tremendous ‘success’ we are overrunning the planet, squandering its resources.

During an interview 56, Denes gives a wise answer as to why she decided to go with a Wheatfield:

I decided we had enough public sculptures of men sitting on horses.

Instead, she hoped to have visitors feel they were not just observing a work of art, instead, living it, stepping into a mysterious landscape in which the famous Statue of Liberty appears to poke out of a country field.

How Denes created this work

The project was not impromptu, as the Public Art Fund commissioned Denes 78 to produce a massive public art piece for Manhattan. To prepare the site for the wheat field, the artist started by getting rid of debris and trash and clearing the enormous landfill.

Denes worked with two assistants and a horde of volunteers from the neighborhood. The difficult task of clearing and preparing the field included transporting two hundred truckloads of dirt from outside, digging 285 furrows, which was done by hand, and removing the rocks and garbage. The grains were also sown by hand, and the furrows were covered with the soil brought in.

The plantation was tended to and maintained for four months, where workers cleared wheat smut, weeded, fertilized, and sprayed against mildew fungus. An irrigation system also had to be set up.

Harvest

The wheat was harvested on August 16, yielding over 1000 pounds of healthy, golden grains. After harvesting the crop, some of the yields were used as a horse field for New York’s mounted police.

Other parts of the yield traveled to up to twenty-eight cities across the world in an exhibition titled The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger, organized by the Minnesota Museum of Art between 1987 and 1990. The grains were transported by several individuals who also planted them in different parts of the world.

The meaning

With Wheatfield, Denes wanted to abolish the line between the audience and the spectator in the world of art. Speaking to Studio International, she said:

My art had little to do with what I learned in schools or with anything that was going on in the art world.

Explaining on her website, Denes said 910:

Wheatfield was a symbol, a universal concept; it represented food, energy, commerce, world trade, and economics. It referred to mismanagement, waste, world hunger and ecological concerns. It called attention to our misplaced priorities.

Artforum writer Brian Sholis noted 1112 both the simple generosity of the project and that Wheatfield- A Confrontation and can be understood as one of the first occasions on which Denes worked on a scale large enough and in a location public enough to suit her outsized ambition. In the artist’s words, the intervention 13 represented nothing less than food, energy, commerce, world trade, economics.

Denes as pioneer

Denes is among the first female to be acknowledged within the cannon of land art 14, which includes such luminaries as Michael Heizer 15, Robert Smithson 16, Mel Chin, and Alan Sonfist. These men were making heroic artworks that were inert, immutable, and mostly made from inorganic materials.

Agnes Denes also made heroic work of arts, but out of living materials that change the form, grow, are transient, are impacted by geology and hydrology, and ultimately reproduce and die.

Wheatfield – A Confrontation differentiates from other land art pieces through its short lifespan, seasonal ties, and living materials, as well as planting and harvest. The only artist whose works are most closely related to Dense is Alan Sonfist. Alan’s most important work titled Time Landscape 17 (1965-1978-Present)18 features a dense planting of indigenous species on a 25-foot by 40-foot rectangular field in lower Manhattan 19.

The plant grown was native to the place before colonization by the British and is meant as a time shell. While this installation is sympathetic to Wheatfield – A Confrontation, and also located within the urban setting, Denes gains superior potency by placing his work at the threshold of the urban-rural environment, and by virtue of soil preparation, sowing, and harvesting.

Just like many other Land and Environmental works, Wheatfield – A Confrontation also has a political and philosophical edge, yet remarkably accessible to the general public. In any other place, particularly in ubiquitous fields in upcountry, crops and themselves don’t carry any political polarization.

In Denes’s determination to install her piece at the interstitial setting of the urban-rural divide that provides potency to the art – an act of preparing the field and planting that would otherwise not be present in a traditional agricultural setting.

Analysis

Like all other temporary earth artworks, Wheatfield – A Confrontation today exists only within the memory of those who witnessed it and photographs that documented the project.

The images are stunning, and in one of the most reproduced images of the work, Denes stand in the middle of the field, staff in her hand; wearing jeans and a striped button-down, her legs almost completely submerged in the crop, she appears like she could be out on the savanna.

The skyscrapers in the background create a humorous and foreboding juxtaposes: In a contest between a solitary person and the colossal architecture, it is quite apparent who would win. Another striking image captures only the vast field of wheat, and far yonder, the famous Statue of Liberty – the symbol of American freedom seems to emerge from the yellow golden crop field.

However, the most poignant image features the crop field against the backdrop of the World Trade Center. During the creation of the plantation, which started shortly after the construction of the Twin Towers, the giant double skyscrapers loomed in the background like capitalist villains.

Today, it is not easy to see them without the memory of the lives lost during the 9/11 terror attack flashing to mind and all the calamities that have followed; international conflict, two long wars, and increasing religious intolerance. While the world in the wheatfield images is also not perfect, it is hard to look at it and not wish we could go back in time.

In this work, the artist refined both the paradox and the calamity intrinsic in the socio-cultural power structure of the world, particularly the western world.

C. Haberman & L. Johnston wrote in the New York Times 2021:

To look across this wheat field is to see the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island and boat traffic as in a surreal illusion.

Despite the complex urban development, and on the eve of transformation, the site of the yellow gold was a tiny portion of pastoral heaven. The strong mark it made on New York has somewhat appreciated with time and the rapid development of the city.

Wheatfield is also considered a touchstone of feminism 22 – in the project, the artist reclaims the land and celebrates its generative potential.

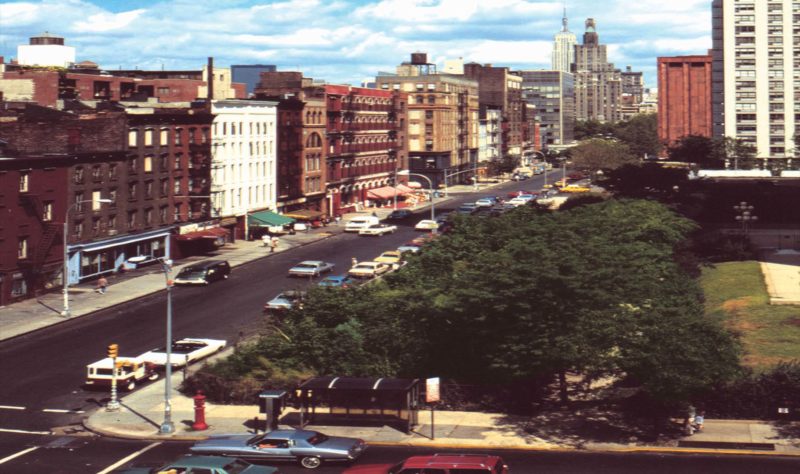

Denes wasn’t the first artist to intervene in New York’s landscape. While the wheat field is long gone, and the location transformed into the modern residential estate (Battery Park), the city still homes to other land art.

Walter de Maria 23 set up his Earth Room 2425 in 1977 in a loft room in SoHo, a few years before Wheatfield. Yet, despite its short lifespan, Wheatfield – A Confrontation was infinitely more accessible than any work of Denes’ peers.

The 2015 edition in Milan, Italy

While her 1982 Wheatfield in downtown Manhattan propelled Denes to international stardom, the Milan project was equally eye-catching.

Stretching over 12 acres, the triangular field of wheat was planted by Agnes Denes along with more than 5,000 workers in February 2015. The project was located in Milan’s Porta Nuova neighborhood, transforming an urban center into an agricultural wheatfield.

The open space, located amidst modern skyscrapers and futuristic buildings of Milan’s rapidly developing skyline, was planted during public sowing.

Around 15,500 cubic meters of soil were shipped to the site, and 1,250kg of seeds were planted using 5,000kg of fertilizer. And since Denes was one of the pioneers of environmental art, no fungicides or herbicides were used.

The installation was a collaboration between three entities – the Fondazione Riccardo Catella, the Fondazione Nicola Trussardi, and Confagricoltura. It was located on what would later become the Library of Trees public park 2627 (Parco Biblioteca degli Alberi).

We are young as a species, even younger as a civilization and, like reckless children, initiate processes we cannot control. I believe that the new role of the artist is to create an art that is more than decoration, commodity or political tool—an art that questions the status quo and the endless contradictions we accept and approve of. It elicits and initiates thinking processes.

During harvesting, the public was invited to take part in the session. The harvesting process employed the ancient methods of reaping the wheat with scythes and threshing it with flails. But the modern operation of combine and baler were also used. A walk down the path allowed the audience to see the growth of wheat to its full maturity.

Both pieces lived in the shadow of the city skyscrapers, and they were both powerful images in the modern lives of New Yorkers and Milanese. The installation of this work brought together a community that unites the public to a much bigger commitment than the project itself.

Conclusion

In this project, nature 30 reclaims the urban space through a simple yet interestingly ecological image – a wheat field grows right at the center of the city of Milan, in the backdrop of the city skyscrapers, thus once again becoming the still point of our mundane lives. It is not just a work of art; it is above all a universal concept, a driving force for building community and social engagement 31.

During a recent interview, Denes spoke of what she intends to do as she nears the end of her career. She said:

I have designed work for New York City on the last open space and hope they won’t stand in the way of it becoming a reality. It would be a magnificent addition to the city.

Since its plantation in 1982, Wheatfield – A Confrontation has endured in public memory as among the most popular land art pieces of all time, a masterpiece instilled with representation and confrontational power. Nature regains the city via a simple yet convincing ecological image: a wheat plantation grows in the middle of New York City.

Though the work lived only for a few months, its resonance and power are ongoing through its documentation. Wheatfield – A Confrontation draws the viewer’s attention to the significance of the archive and the artistic document. It still reminds us that our beloved earth is this way because we allow it to be.