Who is Cindy Sherman?

Cindy Sherman was born in 1954 in New Jersey. She grew up in Long Beach, immersed in the television and film culture of the era. This period was shaped by nuclear war worries, capitalism, and the growing blitz of images selling all sorts of commercial products, including cigarettes, washing machines, bras, cars, and so on.

She credits this climate of her upbringing as a significant influence in her career, including her first major series Untitled Film Stills. In the series, she casts herself in all roles. Sherman becomes both the artist and the subject.

The Untitled Film Stills series was the first significant work that gave her international recognition, and to this day, it is her most well-known project.

Untitled Film Stills

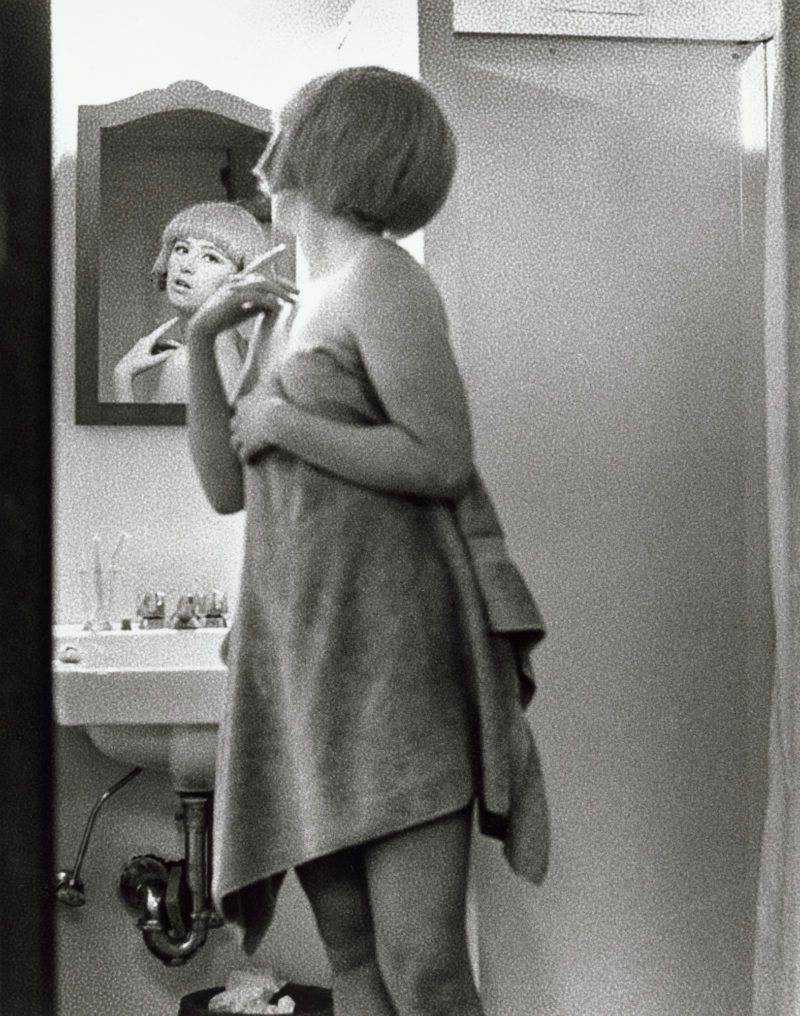

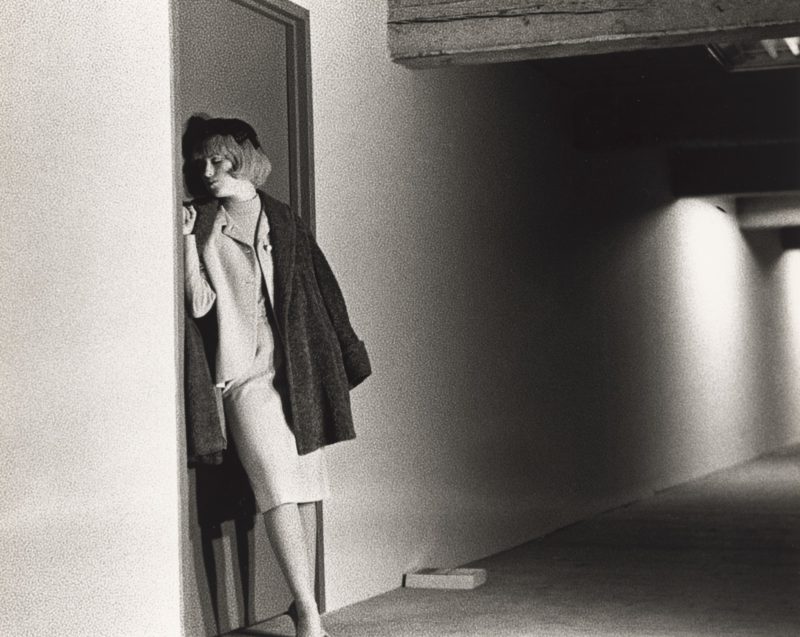

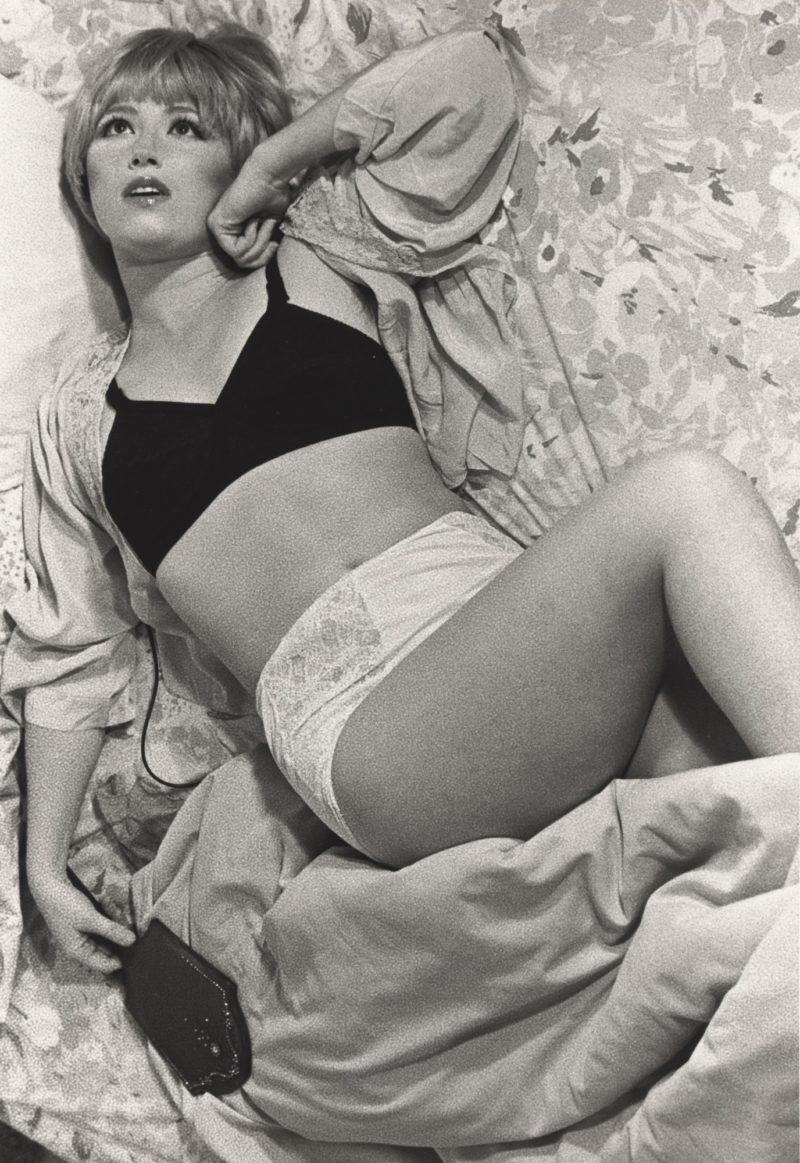

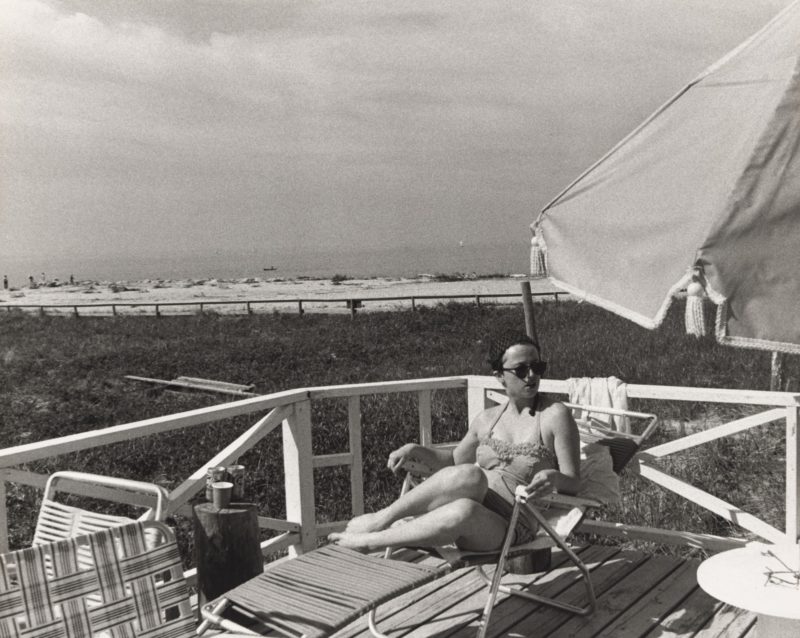

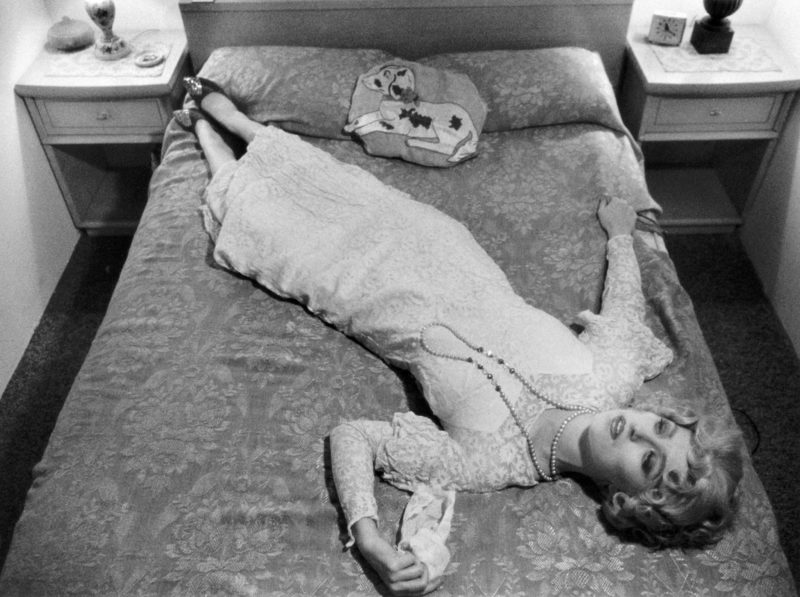

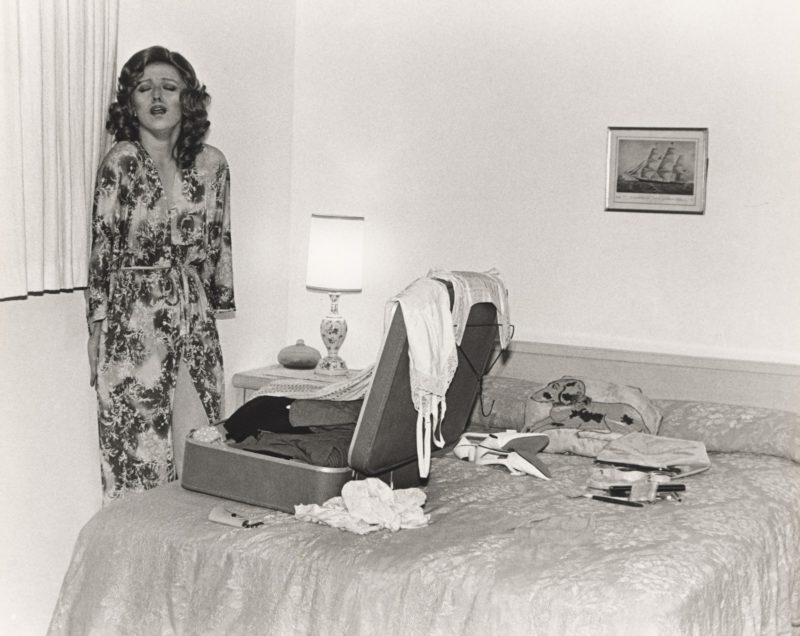

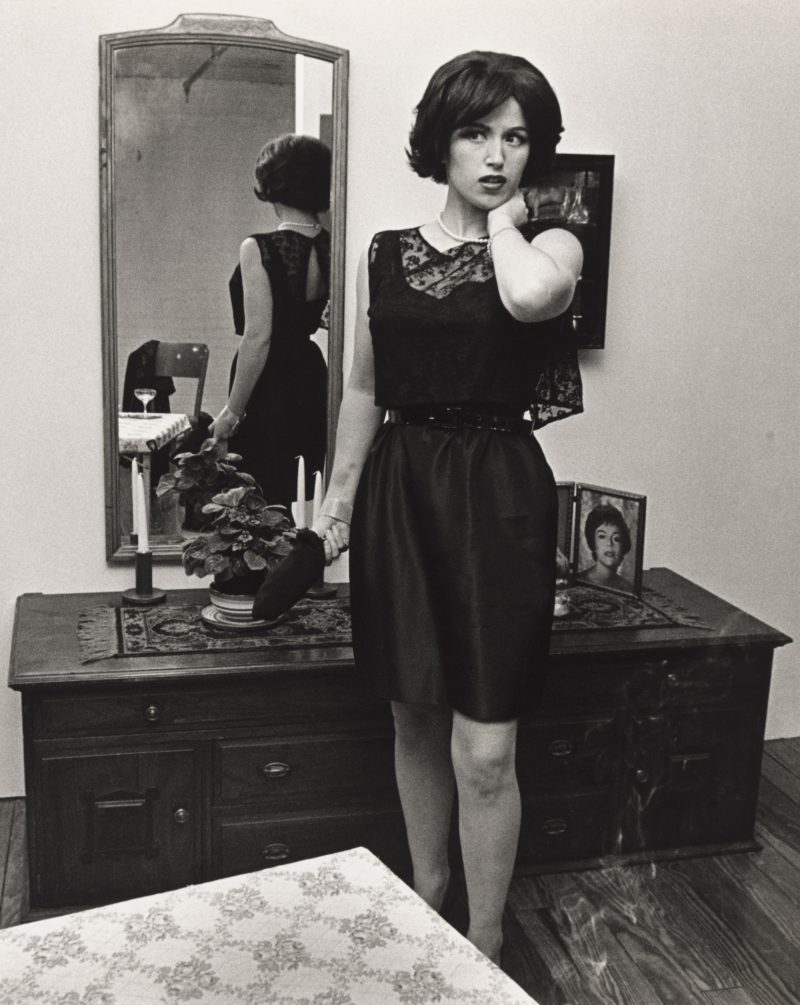

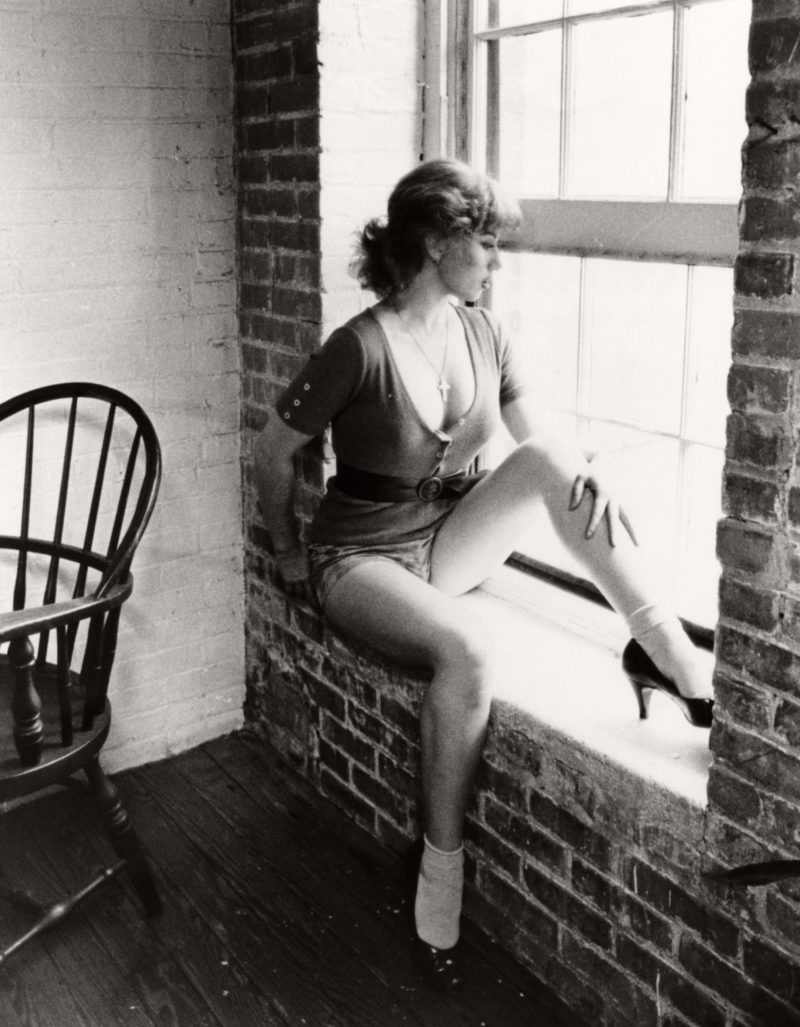

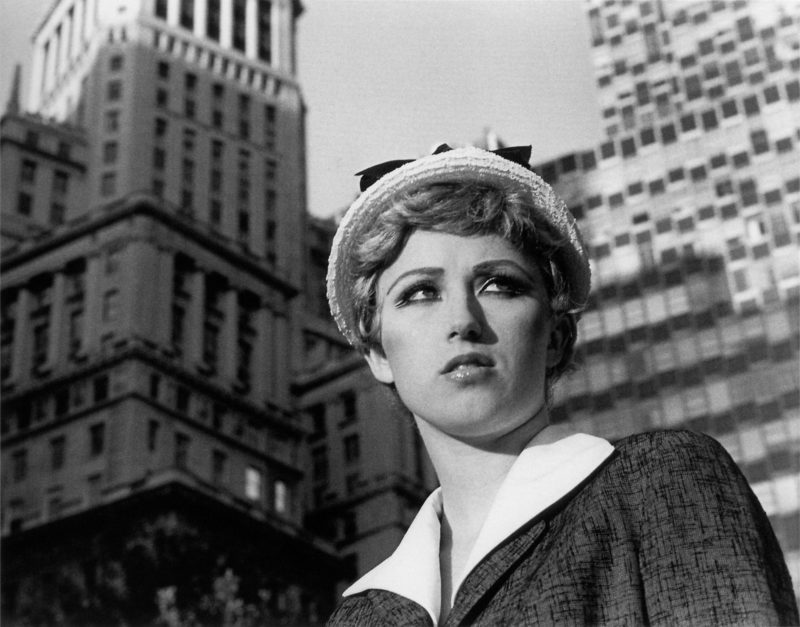

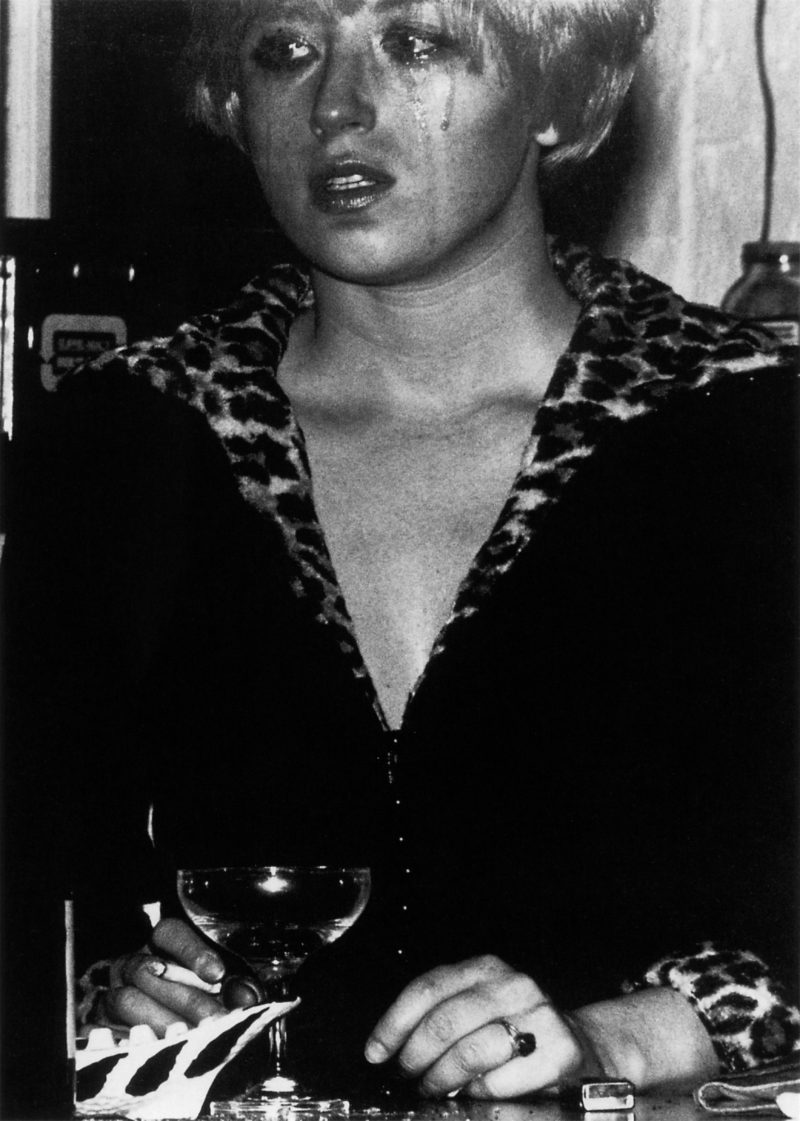

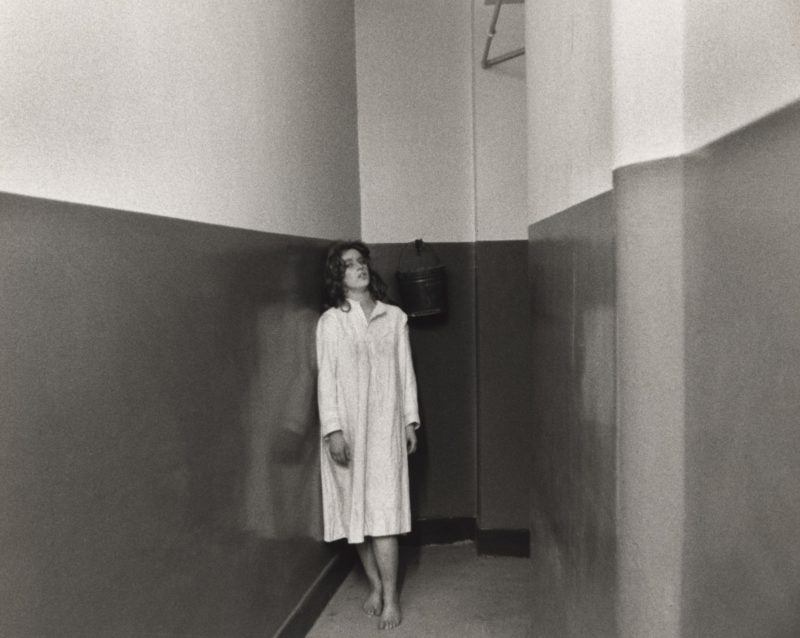

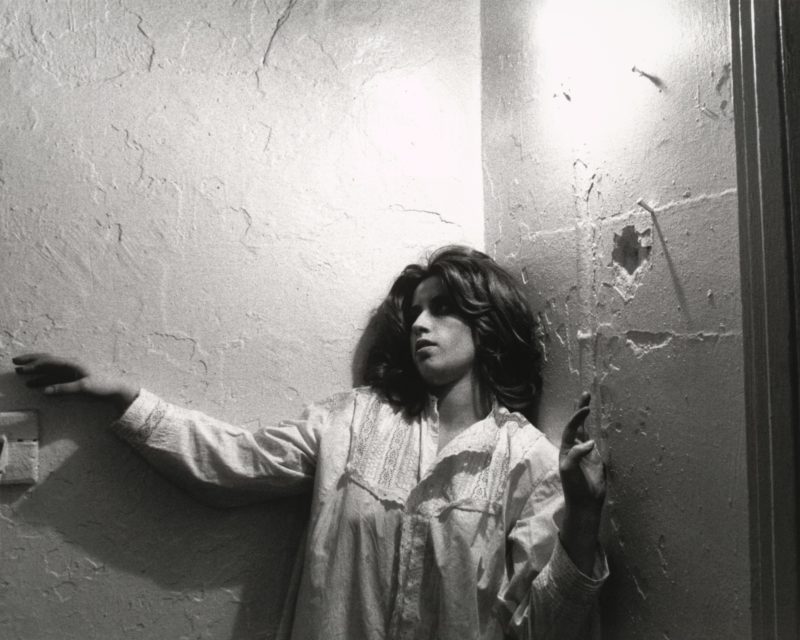

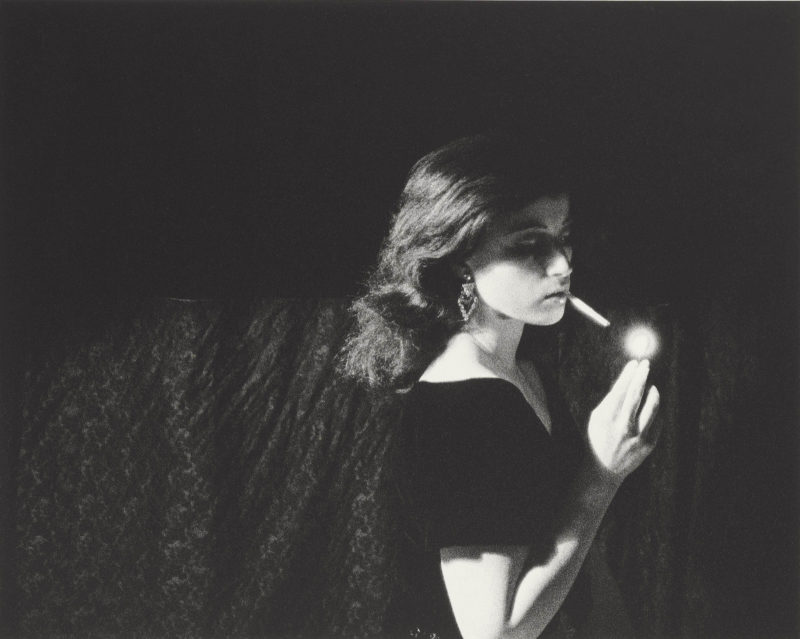

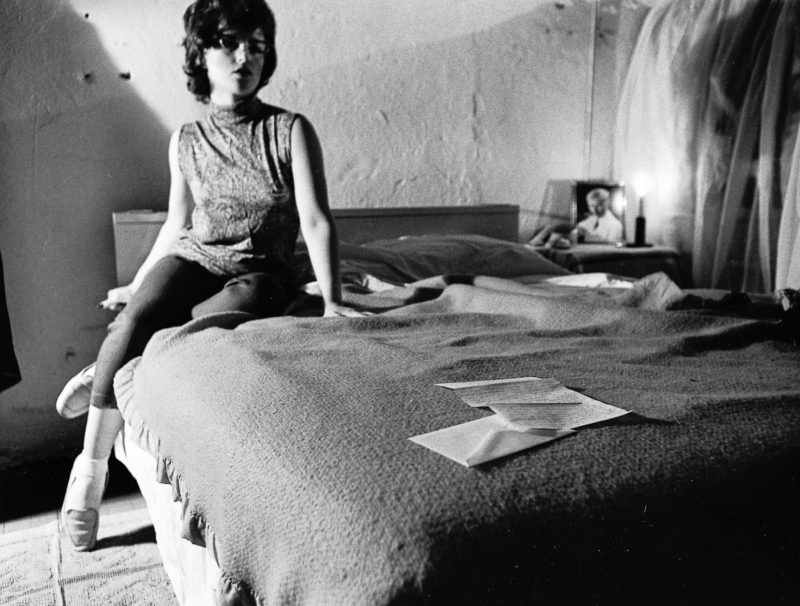

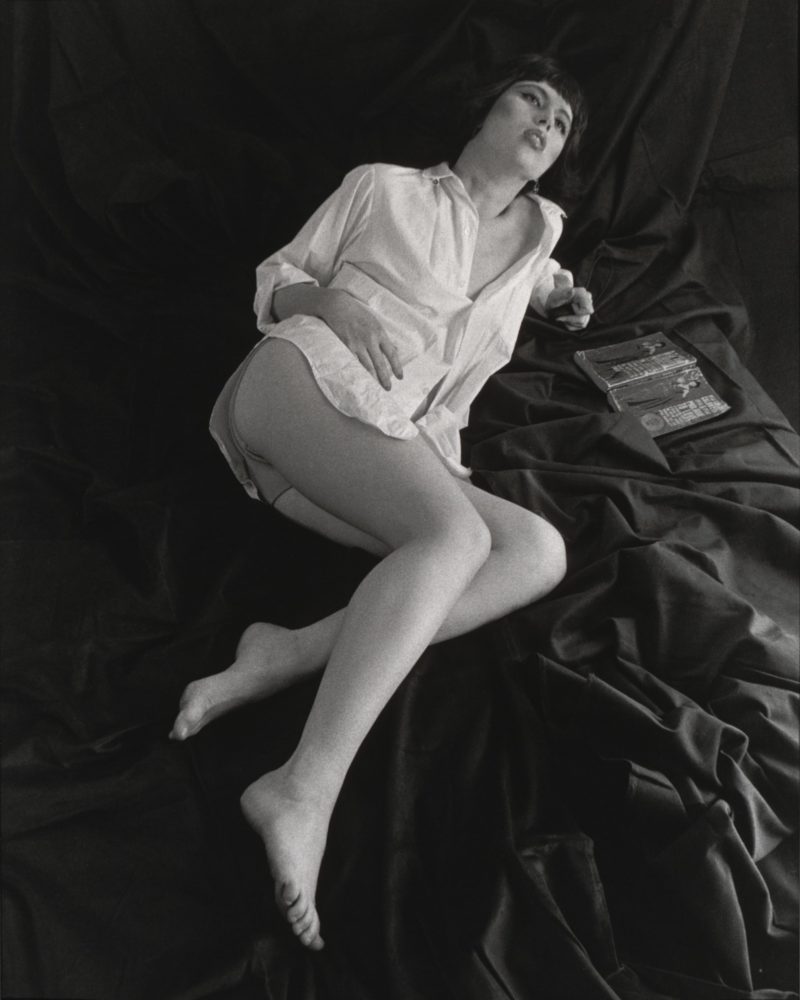

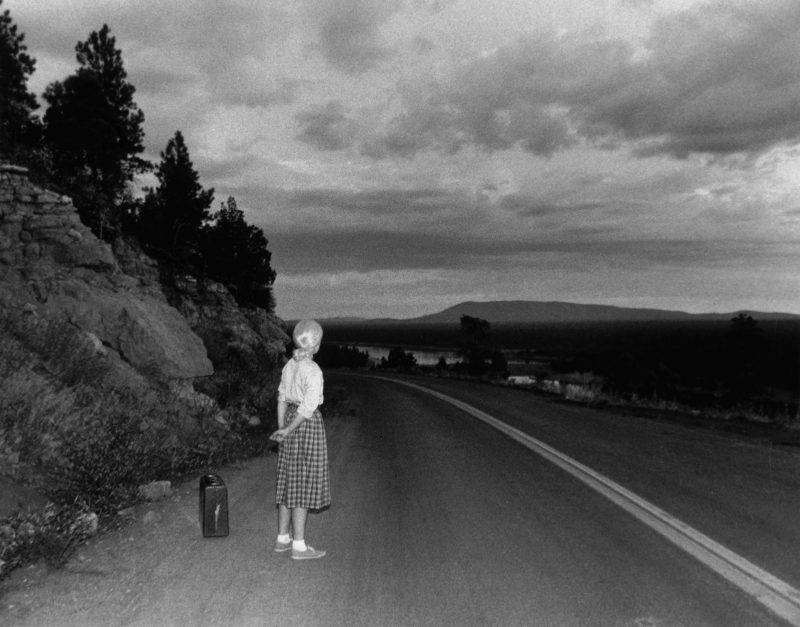

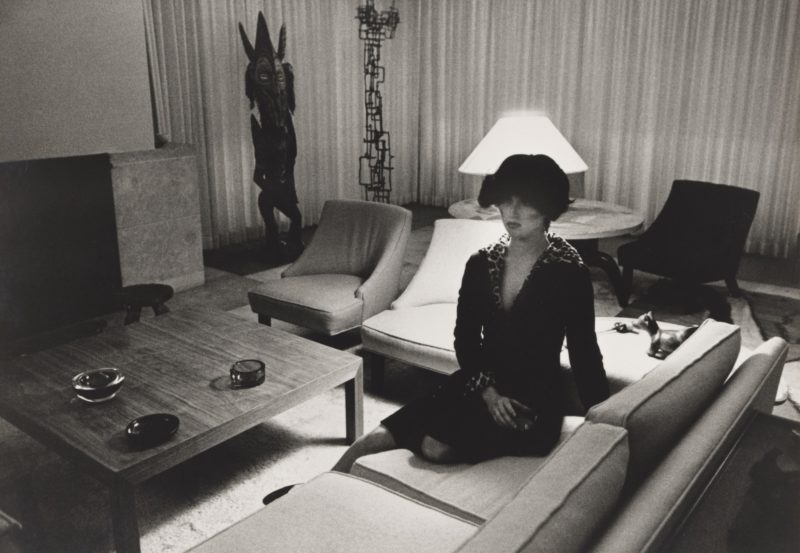

Untitled Film Stills is a series comprising of 69 black and white photographs by Cindy Sherman, which she created between 1977 and 1980. The series’ images are sketchily developed and a moderate 8.5 x 11 inches in size, with no explicit citations or titles.

Her poses in different stereotypical female roles were influenced by the 1950s and 1960s Hollywood B Movies, Film noir, and European art-house films. Untitled Film Stills depicts clichés or feminine types such as the office girl, girl on the run, bombshell, housewife, and many others that are deeply emended in the cultural imagination.

Sherman intentionally makes all the characters in these photographs face away from the camera and outside the frame.

Who is shown in the photos?

The photographs explore the 1950’s cultural imagination utilizing images of the young girls next door pining for a better future; images that are well-known because they represented ideas everyone knew – the photos were roles and faces the audience has seen before.

Despite the series carrying the sense of familiarity, it doesn’t have a specific reference point – the artist was not just refashioning and re-presenting an original. Her assumption of cultural imagery as well as typecast was comprehensive than that. In the series, Sherman was documenting the various faces of American women, including at home, work, and during a social gathering.

Untitled Film Stills doesn’t have a single character in all the stills or any underlying theme to unify the style. Instead, it is made up of a collection of personas that came to existence due to framing, lighting, camera angle, and distance, as if to reference the dizzying group of women dominating the magazines and the airwaves of the 1950s.

Becoming a woman

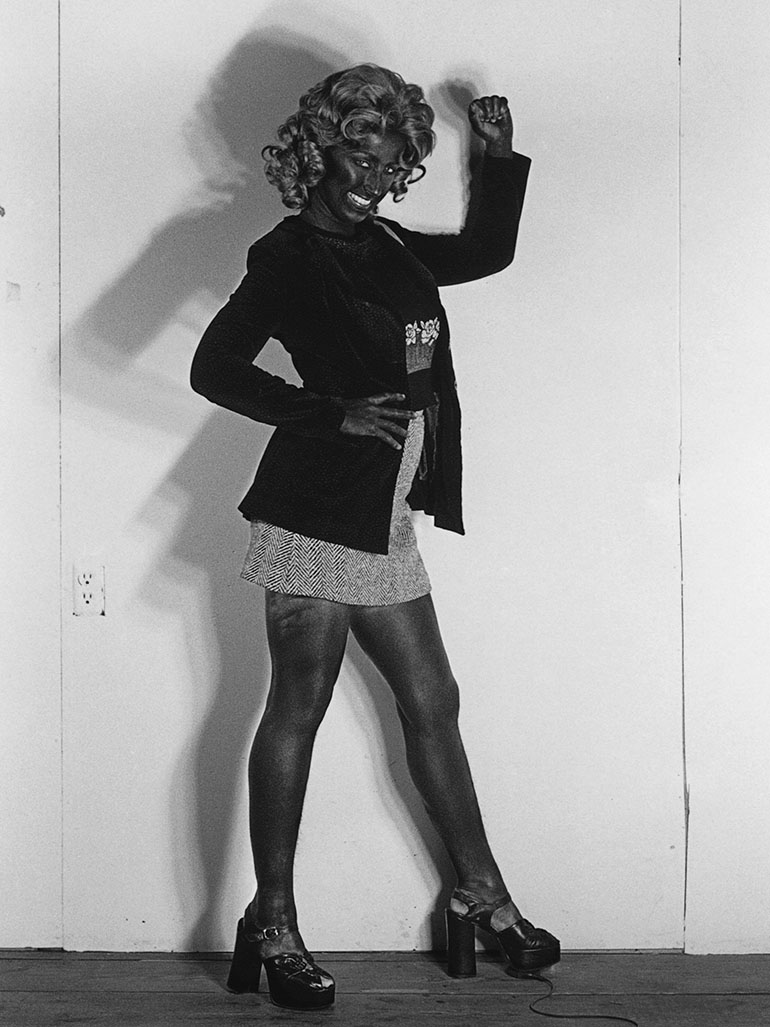

The stills show that you could be everyone while still being utterly no one. The implicit message of the portraits in the series is that representations of femininity are precisely that, little more than mere images. Femininity only needs a little maquillage, a perfect pout, and the right dress, as numerous drag queens have shown in years down the line. Quoting the famous words of feminist 1 Simone de Beauvoir 23, which states, One is not born a woman but becomes one.

Through the Untitled Film Stills, Sherman shows us precisely what – the different women a woman can become. The images in the series do not only represent the traditionally prescribed boundaries of feminine character, but they also portray images of possibility. After all, the artist herself becomes, though transiently, all these women.

Makeup & femininity

The artist emphasized the role-play characteristic of both identity and femininity. And it is no incident that women often denote the process of getting ready as “putting on their face.” For many decades, lipstick and mascara have been women’s war paint. Putting on makeup is not meant just to define a woman but rather, to determine what kind of a woman she really is. Is she a glittery lip gloss type of girl, or a lipstick kind of girl? Is she the type of woman who wears too much makeup, or the type that favors a bare or natural face? Therefore, it is a misnomer to say that a woman wears makeup to look beautiful; instead, women wear makeup to tell the world who they are.

Sherman’s motivation

In the Making of Untitled, the artist sheds light on the journey of the series Untitled Film Stills:

I suppose unconsciously, or semiconsciously at bet, I was wrestling with some sort of turmoil of my own about understanding women. The characters weren’t dummies; they weren’t just airhead actresses. They were women struggling with something, but I didn’t know what. The clothes make them seem a certain way, but then, you look at their expression, however slight it may be, and wonder if maybe ‘they’ are not what the clothes are communicating. I wasn’t working with a raised ‘awareness’, but I definitely felt that the characters are questioning something – perhaps being forced into a certain role. At the same time, those roles are in film: the women aren’t being lifelike; they are acting. There are so many levels of artifice. I like that whole jumble of ambiguity.”

How the project evolved

As the years went by, there were significant changes in the images in the Untitled Films Stills. Starting from the 1980s, Sherman’s aesthetic underwent two distinct metamorphoses. She started shooting in color and began using projected photographs of the environment behind her instead of shooting in a real physical location.

This not only created a more superficial depth of the field, therefore flattening the image, but it initiated Sherman’s shift towards even more segregation and alienation – a new trend that would also present in her later work in Office Killer. Her new approach demonstrated not only how lonely her women were, but now they were not allowed outside, just like the character in the Office Killer. The locations for her shoot would become nearly entirely internal.

Shortly after, another notable change occurred in the series: the images went horizontal, more like the shape of a movie screen. Sherman’s photographs were even more confining, shot entirely indoors, with no sign of an outside world whatsoever. The facial expressions of the characters throughout the series were more intense as well, and more emotional than in her previous projects. However, these were not traditionally centerfolds.

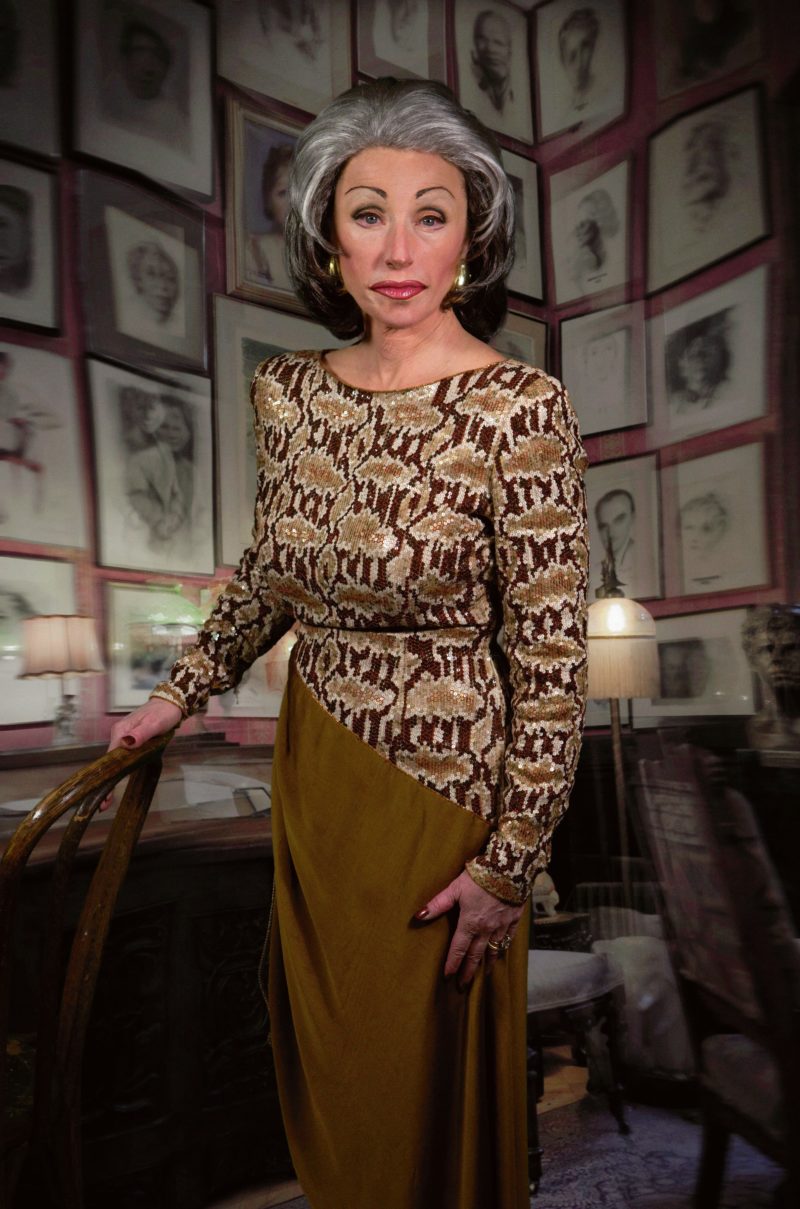

Sherman & Vogue

Sherman took a break from working on the series to create fashion images as commissioned by a renowned designer Dianne Benson for a magazine called Interview and a collection commissioned by French fashion store Dorothee Bis for the Vogue magazine. And just like Sherman’s works in the Untitled Series as well as other centerfolds, these images were also atypical for their projected purpose. Described as “silly, angry, dejected, exhausted, abused, scarred, grimy, and psychologically disturbed,” the images appear to attack the constraints and expectations placed upon women by the fashion world.

After this experience, Sherman had this to say:

From the beginning, there was something that didn’t work with me, like there was friction. I picked out some clothes I wanted to use. I was sent completely different clothes that I found boring to use. I really started to make fun, not of the clothes, but much more of the fashion. I was starting to put scar tissue on my face to become really ugly.

Analysis

This series scrutinizes the 1950s feminine iconography from the perspective of the 1970s. Sherman’s characters are mysterious women of inquisitive strength and belligerence. While they may be alone in the photos and their space confined by the limitations of the frame, they are in total control of that very space.

In all of Sherman’s images, men are noticeably and consistently absent. Even in her fashion photos, the photos are antagonistic. Her characters (women) refuse to parody traditions of femininity and expected glamour, the type of attractive connivance often associated with conventional fashion images.

One thing that is more significant about Untitled Film Stills is not just about the art of the deception, but also the artificiality of its creation; the fact that it is nothing but a mere painting on a surface, an appealing shell.

The art historian Rosalind Krauss described the Untitled Film Stills as copies without originals.

Sweat, humidity, and fear

Centerfolds beckon the audience to connect with it, just like a Playboy model invites the viewer to come closer and interact with her. But Sherman’s photographs are alone, and none of the characters beckons the audience to move closer.

This is also evident in all Sherman’s images, including those that have a coquettish charm. Sherman never implies that you touch her. Even in the pictures in which her character is depicted as more attractive in the conventional sense, such as in the Untitled Film #3, the purpose of the pose is so manikin-like that isolated artificiality encourages the separation between her and the audience.

In the artist’s notes for the series, she highlights several lying-down positions, including “sleeping, fallen, or thrown, unable to walk, and lounging.”

Also, none of the artist’s centerfolds is the character done up. The hair is usually sweaty and mussed, while the faces are glistening and shiny. However, it is the kind of shiny that would never feature in the pages of, let’s say, Playboy. The shine in Sherman’s images is not an orgasmic mist kind; instead, it is the shine of sweat, humidity, and fear. And if it is erotic, it is far from the eroticism of doctoring, but the shine of a lady without a makeup artist or stylist.

However, there is a similarity between Sherman’s centerfold and other conventional centerfolds- a similar emphasis on creation and arrangement, nevertheless disparate their execution and intention.

In conventional centerfolds, the character’s persona is constructed on her prudently modeled image, just like the women in Sherman’s series. Even though Sherman’s series is built around the idea of the unreachable, it too is constructed around the idea of the performance as conveyed through the arrangement. It is the dialect of body parts of body language. It is like it tries to communicate the notion that who you are is how you pose, and how you pose is who you are.

Office Killer, 1997

The glamorous facets of the many women who dominate films, commercials, and cocktail parties mask the real body underneath, a rare, wet, and bloody expanse. This would become apparent in Sherman’s later projects, ultimately sprouting into the cavernous and damaged bodies of her famous work Office Killer.

The Office Killer movie represents Sherman’s only venture into filmmaking despite the industry having a huge bearing in her career. The film is set in the 1990s, a period in which the traditional limitations between exteriority and interiority, and by a stretch the public and private, have potentially been almost eradicated.

The artist produces a material body that locates the irreducibility of the two worlds, even if it must be retained with Scotch tape and Windex to remain so. This conflict between the inner and the outer, between the real underneath and pretty surface, between raw insides and painted face, only grew louder and muddled as Sherman continues to produce subsequent works.

Recurring themes

In her 40 years of work, Sherman has consistently conveyed the theme of isolation, coupled with aggression and refusal to pay by the conventional rules of how women or people, for that matter, should behave. There is strength in the solitude of the characters in the series. They are alone. After all, they have decided to be alone because their appearances are prophylactics from a realm of contagion, disease, and weakness. Even in fashion shoots, Sherman’s women look away, leave their hair unkempt, to apply their makeup shoddily if they even apply it at all.

Conclusion

Throughout Sherman’s images, the audience can spot duality, much like there is a dichotomy in her characters – two ways of looking as well as being looked at.

Sherman mimics the type of image often found in traditional fashion magazines. She subverted restrictions normally imposed on women regarding their physical appearance and behavior while also implying that the flawless body, which was featured in her previous fashion works, is only half of the equation.

The other half is on the other end of the scale – the disgusting, the grotesque, the internal, and the imperfect. It is this other half that was never presented that caught the attention of Sherman.

The faces we usually see on the cover of the leading fashion magazines, the models Photoshopped and designed to perfection, are simply a shell hiding what is lying beneath. Sherman and her Untitled Film Stills series wanted to move past and inside the surface.