Birmingham Project

Dawoud Bey’s 1 career focuses on portraying American youth as well as those from marginalized communities. He does so with an uncommon degree of sympathy and complexity.

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing

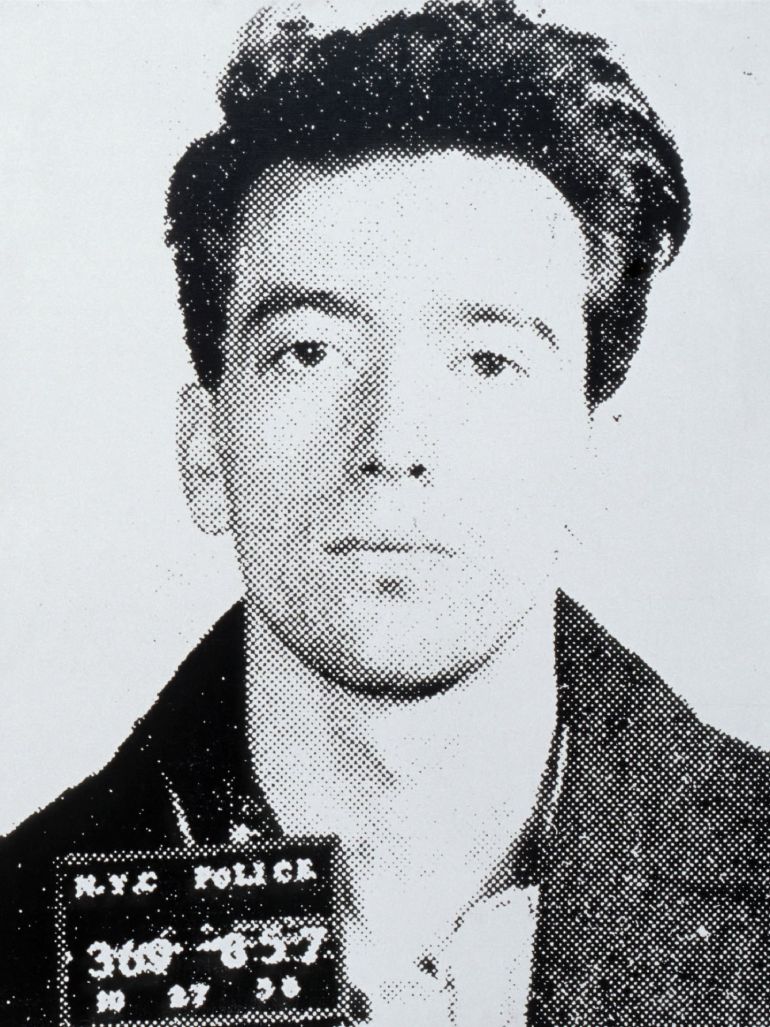

His Birmingham Project is a deeply felt and abstractly rich tribute to the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing 23 in the city of Birmingham, Alabama 4, on September 15, 1963. During the stated date, the Ku Klux Klan deployed dynamite in the lower ground floor of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, a venue that had been previously used a the headquarters for Martin Luther King Jr’s anti-segregationist protests.

The explosion killed four girls getting ready for Sunday service – Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley, all 14, and Carol Denise McNair, 11. A few hours before the bombing of the church 5, across the city, two African American boys, James Johnny Robinson, 16, and Virgil Ware, 13, were murdered by two white men who were coming from a segregation rally.

What Dawoud Bey’s photos show

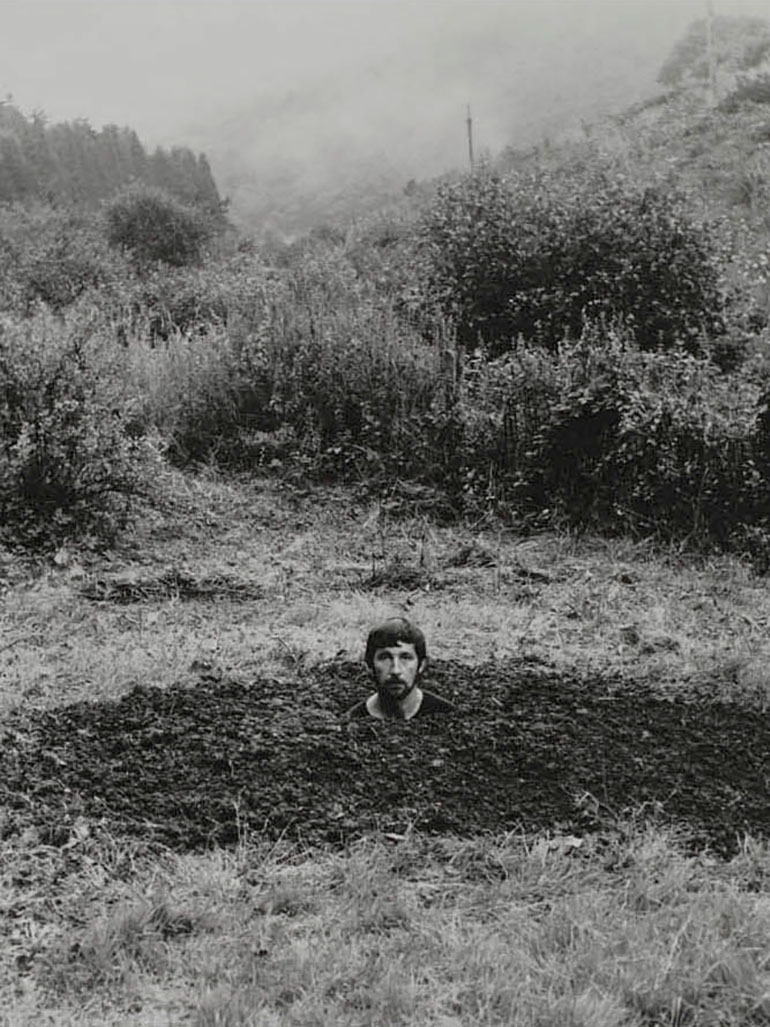

The photo series, created in 2012, features images of the church community, each having fifty years between them. Every diptych has a young person the same age as one of the victims of the 1963 hate crime, paired with another of an adult 50 years older. This signifies the age of the child had they been alive today.

Bey’s motivation

Bey remembers when he was 11 years old. He says:

My parents brought home a copy of The Movement 67, which was a book of photographs of and about the civil movement by several different photographers.

He remembers seeing a photo of the “Fifth Girl” Sarah Collins lying in a hospital bed with white cotton covering her eyes and her skin disfigured from the explosion. And 40 years later, that image was still burned in Bey’s memory 89:

Thirty-eight years after seeing that photograph in the book, I sat bolt upright in bed one morning after that image appeared to me in my sleep. I’m not sure what shook it loose, but I knew that I need to go to Birmingham to see the place where this traumatic event had occurred and to think about how I might make some work in response to that moment.

Reactions

After visiting the church in Birmingham and stating his intention of creating a series to commemorate the 1963 attacks, he was met with an unusual response from the minister of the church. Bey recalls:

Before I could get too far, he interrupted me to tell me that, ‘Here at the 16th Street Baptist church, we’re not about all that business. We’re about the business of Jesus Christ, and if you want to make some work about that, we’d be happy to work with you.’

Bey realized that the history he hoped to deal with was far complex than he anticipated and that Birmingham’s residents might think differently about the events of 1963 and their aftermath.

His approach

Bey spent five months finding his subjects. They had to be the right age and live in Birmingham, which turned out to be more challenging than anticipated.

The photographer, of course, was clear about the type of people he was looking for to complete the project – people from the black community. His outreach method included soliciting volunteers on Craigslist, fliers, word of mouth, school visits, and enlisting local church ministers’ aid. He continued the outreach even while he was shooting the portraits of other people. Bey also was invited to speak at the City Council meeting by the mayor of Birmingham, William A. Bell.

I wanted to engage the idea of the passage of time and the fact that those young people never had a chance to live out their lives.

The African American adults that became the subject of his photos all remembered the events of 1963. Some even knew some of the victims of the shooting since they were the same age.

Style

Birmingham Project follows the typical creating process of Dawoud Bey, of maintaining full control over the aesthetics of the portraits. However, he collaborated with his subjects closely, talking to them, allowing them to pick their clothes, accessories, hairstyles, and ensuring that they were comfortable.

The completed series of Birmingham Project consists of 16 diptychs – 32 paired images. The subjects in the series never met each other. Bey took their portraits separately and only paired them after.

“They had to ‘complete’ each other in some way.”, Bey said. “Pairing them as diptychs allowed for a way to imply the passage of time in the still photograph,” he stated. Through pairing them, each diptych encompassed 50 years.

How Bey paired two subjects

Bey decided on which two subjects to pair in a diptych by different factors. He based his process on how they related in several different ways. This could be through their gestures or expressions, the composition or even personal aspects. Bey tried to make two works resonate closely in relation to the other. This tone strengthens the nostalgia and the emotional effect of the diptychs.

Locations

The photos were taken in different historical places; half of them were shot at the Bethel Baptist Church, the headquarters of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights and the location of the bombings. The remaining half was taken at the Birmingham Museum of Art, which had restricted admission for African Americans to only once a week in the early 1960s.

Conclusion

Birmingham Project is a typical Dawoud Bey piece. By establishing a connection between the modern persons –ordinary individuals with day-to-day lives – and the people’s resonance lost to a struggle that is still witnessed today; Bey makes the past come alive. And in doing so, he draws attention to the powerful way in which photographs stamp subjective experience onto contemporary events and social history.

Despite the 50 years gap between the paired subjects, they speak to fused histories and shared destinies: adults who help forge a path of acceptance of their bravery and the largess who may well do the same for the future generations.