Intro

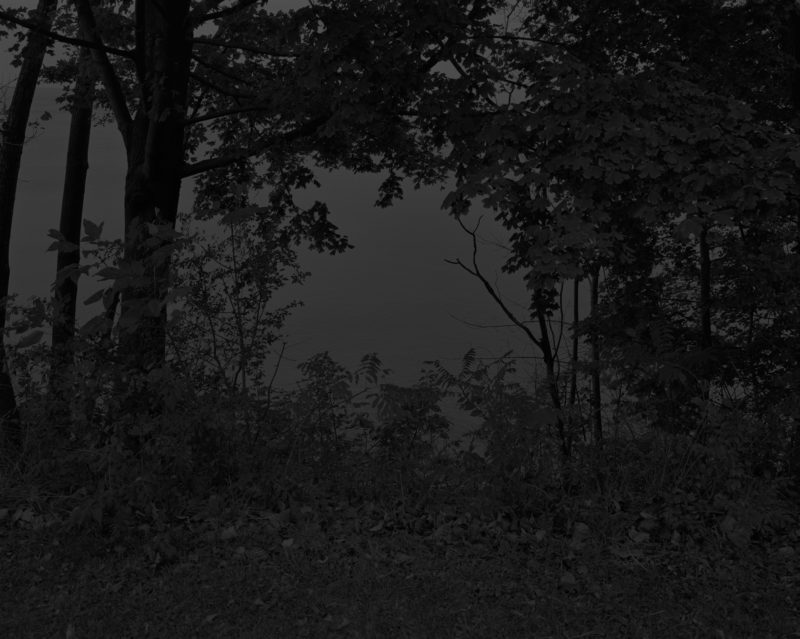

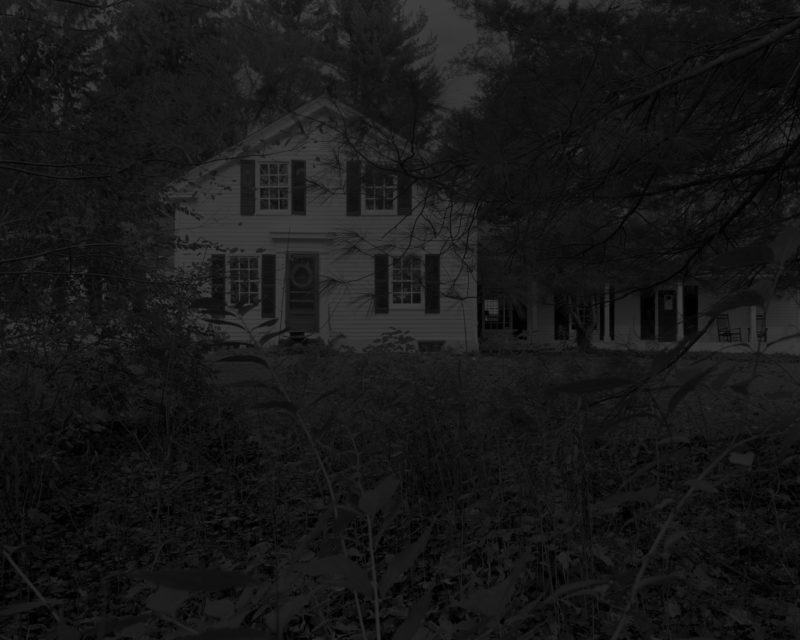

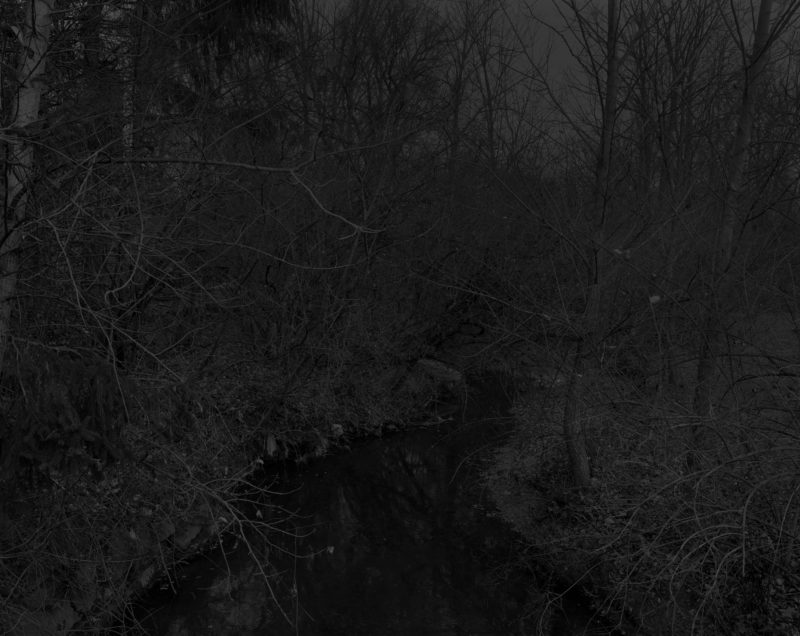

Night Coming Tenderly, Black is the work of photographer Dawoud Bey 12. It consists of large-scale 3 portraits that dive into the literary history as it tries to re-create the practice of the slaves escaping on the Underground Railroad. When Bey visited the outskirts of Cleveland in 2017, he realized that the landscape had not primarily changed since thousands of slaves escaped through it more than two centuries ago, seeking freedom.

Bey said in an email interview:

I ranged far and wideout there since there were expansive rural landscapes that looked as they might have in the 18th and 19th centuries. The landscape and the history there have not been built over.

The artist did not intend to trace the steps passing slaves in a literal meaning. Instead, he wanted to reimagine and evoke the sensory and spatial experience of movement through the landscape of fugitive slaves as well as recreate a hugely significant time in the history of America.

This series was a sequel to The Birmingham Project 45, a project from 2013 in which the artist focused on the 1968 bombing of a church 6 in Birmingham, which killed four young African-American girls during the incident’s 50th anniversary.

What it shows

The photographs in this series are some of the most sensual and layered. These are sights that are at first confining, then liberating, when you understand them through the lens of history.

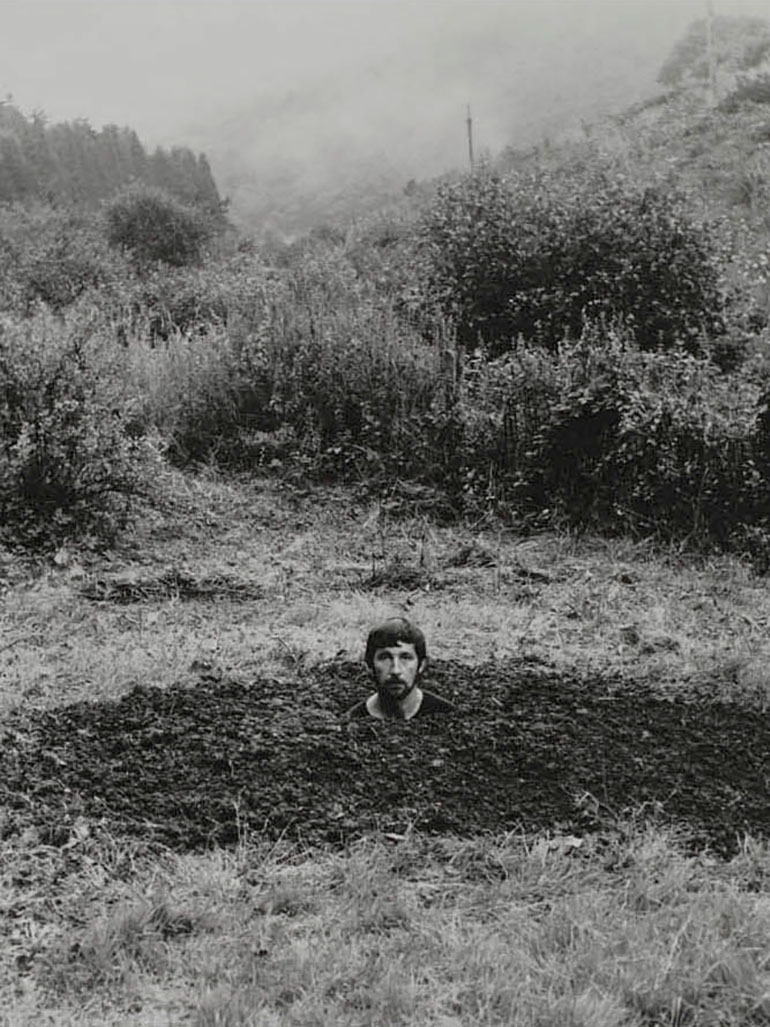

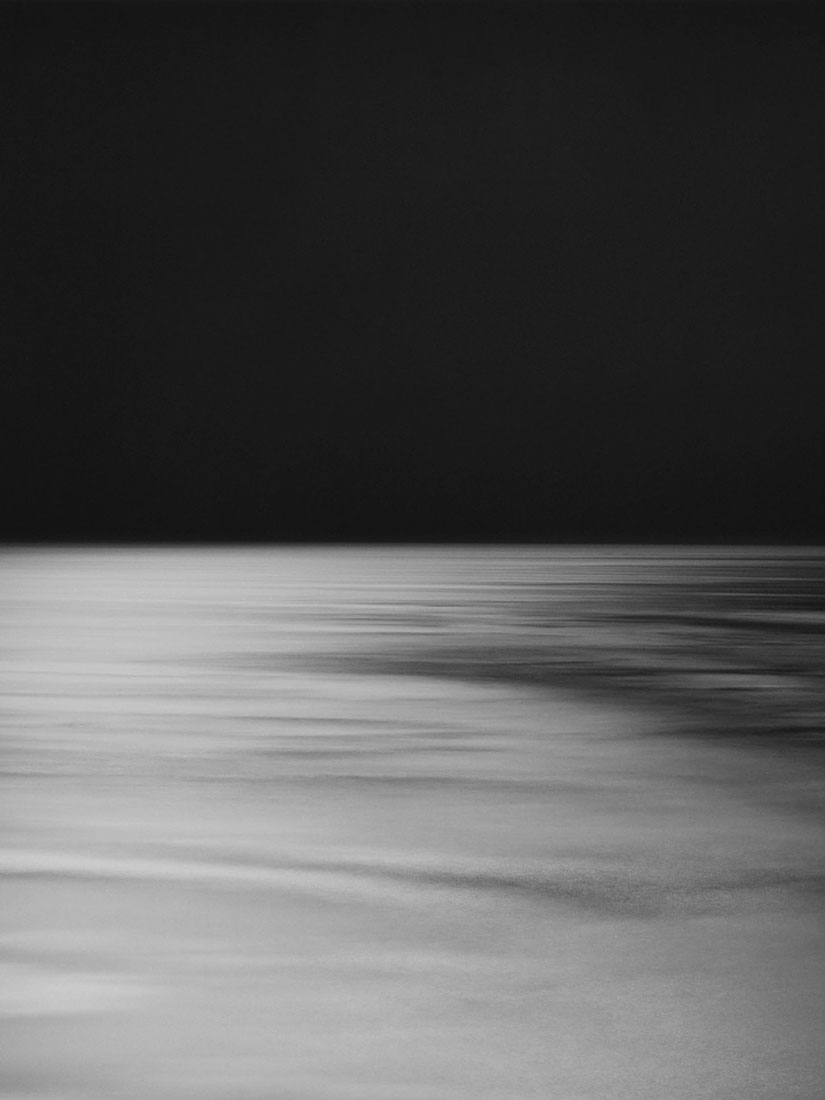

In their grandeur and mystery, they transform houses masked in darkness, bodies of water, and fields into an emblematic hope. A pristine fencepost and a homestead visible through the haze of the darkness; a wetland glistening in nightfall; a jungle thick with small trees; an image of Lake Erie, with the expansive sky and horizon forewarning the freedom that lies beyond.

The Underground Railroad

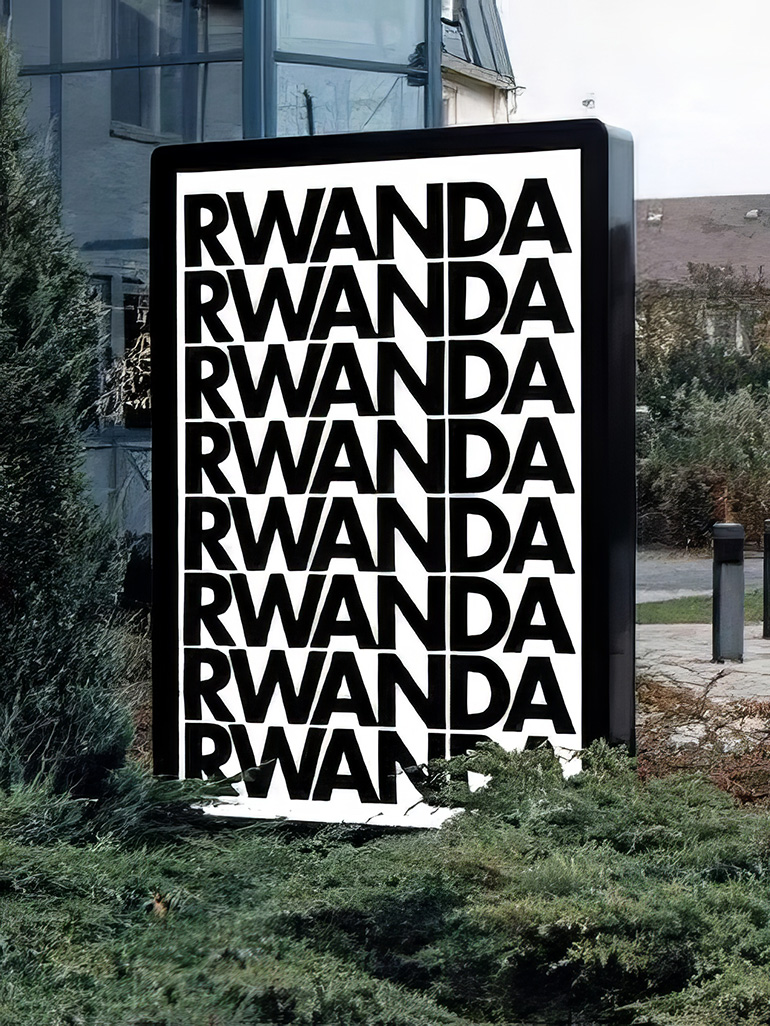

Night Coming Tenderly, Black contains 25 large-scale images of homesteads with wooded or grassy grounds that are believed to have formed part of the said Underground Railroad. The Underground Railroad is an actual invisible web of routes and safe houses believed to have made the final way station for more than 100,000 fugitive slaves escaping to Canada. But according to the artist himself, some of the images may be of actual Underground Railroad.

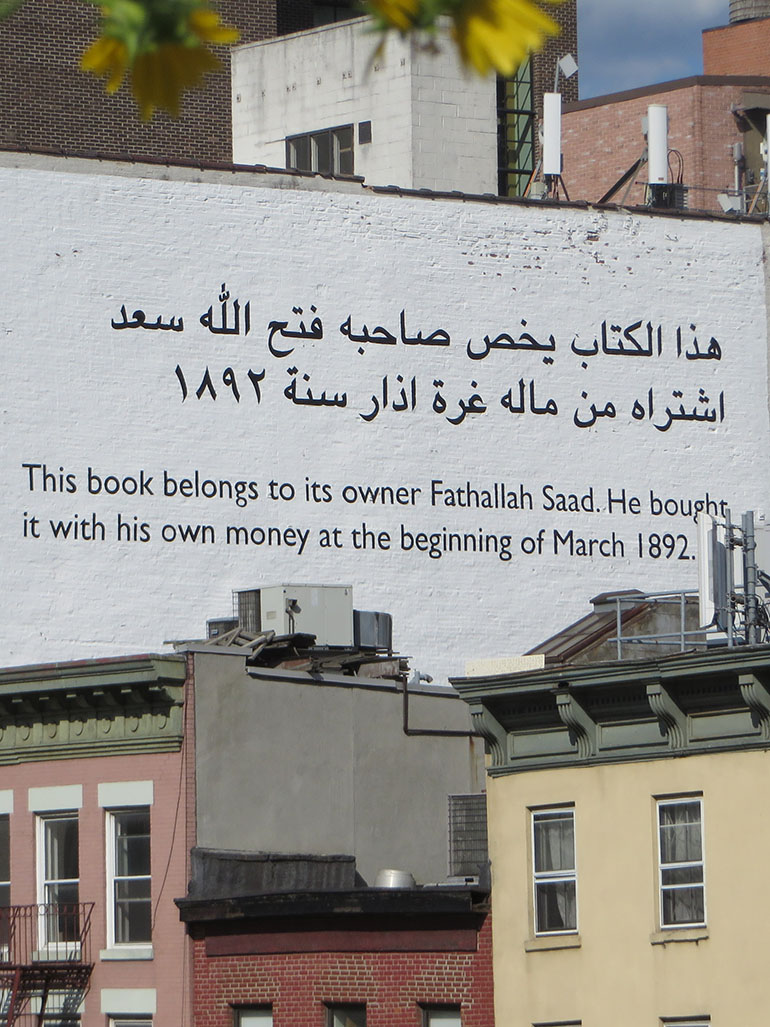

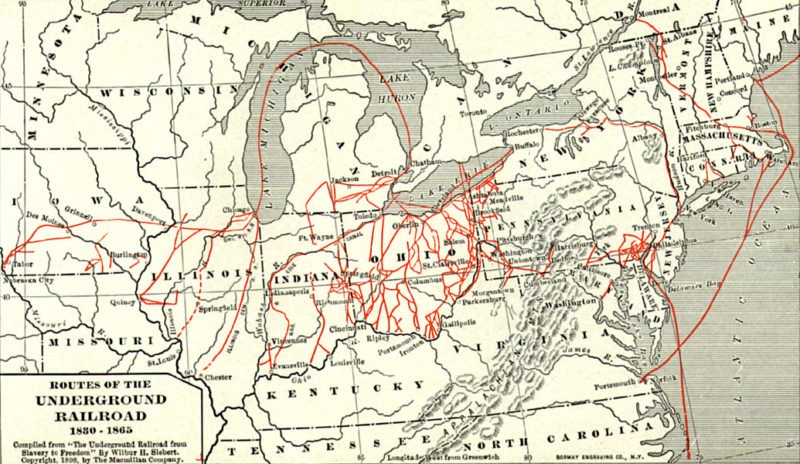

The whole map of the underground railroad. The Underground Railroad was not an actual railroad, but a network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada. Image: Public Domain

Some of the photographs, to the extent that we know, are actual Underground Railroad sites, and the majority of them are placed in the landscape that I identified in proximity to some of those locations, where I could make work that suggested the movement of fugitive slaves through the landscape.

Today, there is very little to no documentation of the Underground Railroad – an eighteenth-century web of secret routes and safe houses preserved by courageous black and white conductors, which helped the escape of slaves to Canada and free states of the north.

The locations

While most of Bey’s works have focused on urban settings, he faced some challenges creating Night Coming Tenderly, Black. He had to ensure the images he created evoked the history of mainly rural areas. He photographed most parts of Cleveland, but he often found the city’s urban personality to be slightly inconsistent with the historical accounts.

His research took him to a more rustic town in Ohio called Hudson, some 30 miles southeast of Cleveland. The landscape of Hudson had significantly changed from the years before the Civil War, and still, several Underground Railroad networks remain.

I wanted the photographs to almost involuntarily pull you back to the experience of the landscape through which those fugitive black bodies were moving in the 19th century to escape slavery. So I had to learn, for the first time, how to make photographs in the kind of space.

Exhibition at St. John’s Episcopal Church

Bey was initially unconvinced when the artistic director of the Front International, Michelle Grabner, proposed that he consider installing this series in St. John’s Episcopal Church. Bey recalls saying to Grabner at the time:

I am a white box artist who makes works about nonwhite box things.

Bey says he sees exhibitions of his images as refreshing, interactive, and challenging conventional art institutions through imagery, which is often overlooked by them.

But the historical importance of St. John’s Episcopal Church led to a change of stance by Bey. He said, St. John’s was the final Underground Railroad station that fugitive slaves who had made their way to Cleveland would take refuge before making their way to Lake Erie and then on to freedom in Canada. To have the work shown in a space that had once been inhabited by fugitive slaves was deeply meaningful.

The meaning of the title

This series is also a tribute to poet Langston Hughes (1901-1967) and photographer Roy DeCarava (1919-2009), who each played significant roles in addressing the experience of African Americans by representing what DeCarava described as a world shaped by blackness. Bey was inspired by De’Carava’s incredible ability to print a spectrum of dark hues, making him picture landscapes of twilight uncertainty.

On the other hand, Hughes Langston wrote a poem titled Dream Variations 78 in 1926, in which he yearned for a time when the black American worker, extremely tired by the daily hustle of hard labor and prejudice, might be truly free. However, this freedom, he imagined, would not be obtained in the glare of daylight, but instead under the ominous, protective cover of the night.

Upending a dominant literary conceit, blackness, rather than whiteness, functioned as an allegory for hope and transcendence. A night coming tenderly, black like me, (Hughes poem), helped the fight for racial equality and justice. The metaphor in the poem is central to Dawoud Bey’s series Night Coming Tenderly, Black.

Influenced by Roy DeCarava

Bey has never stopped waxing lyrical on the influence of the two figures that inspired his artistic career, especially Roy DeCarava, who was one of the most prominent photographers of his generation. The images he took were visually rich and redolent, and they pushed the aesthetic limits of photography. DeCarava was the founder of the Kamoinge Workshop based in Harlem in 1963, which launched to help African-American artists who were being ignored by mainstream art institutions and global media.

Dawoud Bey noted that DeCarava’s images were characteristically printed in dark and rich color range. In this context, the dark prints served as a symbol for black subjects and experience. Bey says:

DeCarava used blackness as an affirmative value, as a kind of beautiful blackness through which his subjects both moved and emerged. His work was formative to my own thinking early on, and these dark landscapes are a kind of material conversation with his work, using the darkness of the landscape and the photographic print as an evocative space of blackness through which the unseen and imaginary black fugitive subject is moving.

The choice of colors

The first thing a viewer notices when seeing Night Coming Tenderly, Black exhibited is blackness; large-scale photographs printed in colors of charcoal and obsidian with an infrequent shaft of grey. This gives your eyes time to adjust to the tones of the images, and then you will begin to see clearly the details of porches and fences, thickest of branches, as well as daunting, auspicious openness of Lake Erie.

The artist printed these images in a large size to encase the viewer and deliberately dark to reveal his subject matter: He took the photos of the sites in and near Cleveland associated with the Underground Railroad that guided the slaves to liberation.

For his exhibition at the Art Institute Chicago, Bey chose a dense, vibrant collection of 19th and 20th-century portraits from the museums’ collection to install directly outside the exhibition space. These pieces supplement the exhibition by signifying the number of ways that the American landscape has been depicted in photographs. It also displays the position of African Americans within that social and physical landscape.

Analysis

Night Coming Tenderly, Black envisages a historical fight for freedom not in unambiguous black and white or vivid tonal range, but luminous shades of gray. Just like the works of his influencers – DeCarava and Hughes – the images in Night Coming Tenderly, Black refuse to denote the darkness of night as a space of fear.

Bey observes:

It is a tender one, through which one moves. That is the space I imagined the fugitive black subjects moving through as they sought their self-liberation, moving through the dark landscape of America and Ohio toward freedom under cover of a munificent and blessed blackness.

There is no introductory text in this series, and only hinting that it is a conceptual work by merely describing the mission of the show as to imagine the Underground Railroad journey. Many historians have tried to reconstruct this phenomenon, but mostly it existed in the minds of the people.

Conclusion

Night Coming Tenderly, Black continues the artist’s exploration of the past and its relationship as well as its relevance to the modern-day.

The darkness of the images perfectly recreates the experience of moving through the trails and landscape under the cover of the night. The prints are magnificently somber, nearly spiritual objet d’art conjuring the disturbance and gravity of the purpose that you can only imagine an individual trying to regain his independence must have felt. Nevertheless, they are also works of profound beauty, as well.