What was it?

In 1995, Francis Alÿs 1 performed a walk holding a leaking can of blue paint in the Brazilian city of São Paulo. That simple walk was then interpreted as a poetic gesture. Nine years later, Alÿs re-enacted that same gesture with a leaking can of green paint.

Alÿs’s performance provoked so much attention because the artist traced the original ‘Green Line’ that Lt. Colonel Moshe Dayan drew using green wax pencil on a map in 1948, after the end of the United Nations Mandate of Palestine and the declaration of the State of Israel.

This line served as the border 2 between the two countries until another war broke out – The six Day War – in 1967, which led to the occupation of the Palestinian 3-inhabited region east of the Green Line by Israel 4.

Though palpably strange and greeted by onlookers with perplexity, Alÿs’s walk spilling green paint evoked the memory of the green line. It coincided with the construction of a separation wall just east of the green line.

58 liters of green paint

When Alÿs recreated his São Paulo walk in Jerusalem in 2004, it was titled The Green Line: Sometimes doing something poetic can become political, and sometimes doing something political can become poetic. It has also been dubbed Walk through Jerusalem.

Alÿs used 58 liters of green paint and traced the line of nearly 24 kilometers, passing through Jerusalem, as filmmaker Julien Devaux filmed.

He walked past security control pasts and barriers that limit the movement of city dwellers depending on where you are from, but mostly those of Palestinians. Alÿs topped at various intervals to refill his can with green vinyl paint. What is extraordinary about the footage is that a few onlookers engaged with the artist, including security officers, at various checkpoints.

In this walk, Alÿs strolled through what he referred to as the typical city of conflict. His route somehow followed the village in Jerusalem of the ceasefire demarcation line 56 separating Palestinian and Israeli communities since the end of the 1948 Israel War of Independence.

Feedback & interviews

Once he finished the walk, Alÿs presented the documentation to selected members of the public who he invited to react freely to the action and the circumstances under which it was performed.

Alÿs later encouraged critics from Palestine, Israel, and other countries around the world to reflect on his performance. He then incorporated the voices of those critics into the final documentary. The critics were sometimes approving and sometimes skeptical of Alÿs’ action.

The artist conducted different interviews 78 with notable people from both sides – Israel and Palestine – while they watched a preview of the walk. These interviews offer a variety of views on the situation in the region regarding the status of the armistice line of 1949 and how art and power can be used in situations of conflict. Most of the interviewees, though, appeared to lean on the side of the Palestinians 910.

Green Line video

Background

This region was a contested border that was universally endorsed under the supervision of the United Nations in 1949. It has since been referred to as “the 1949 armistice line” but officially lost its boundary position in 1967.

The structure and concept of The Green Line are evidently simple. Yet, the performance conjures a complex web of associations concerning the past, present, and future of the communities living within this region, as well as the motif prevalent in much of modern art.

First and foremost, the work calls to mind the current status of the 1949 armistice line the artist partially traced, more than six decades after its establishment in 1948.

The line has been considered an undesirable, random source of conflict and division, a relatively flexible and imposing yet essential boundary between Israelis and Palestinians. A line that is viewed in favorable eyes compared to the relentless, gigantic separation walls constructed under the guidance of Ariel Sharon 55 years later, a line that provides the promise of future peace.

Despite evoking the memory of the source of conflict between Israelis and Palestinians and causing consideration of the highly contested past and future of Jerusalem, Alÿs’s work also relates to his own oeuvre, which he conceives of as a narrative that is assembled by the episodes that are his artwork.

Exhibition & additional artworks

Although this performance survived as a documentation of the artist’s stroll, it should be viewed as a crucial part of the project, which was displayed at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and David Zwirner Gallery 11 in New York 12.

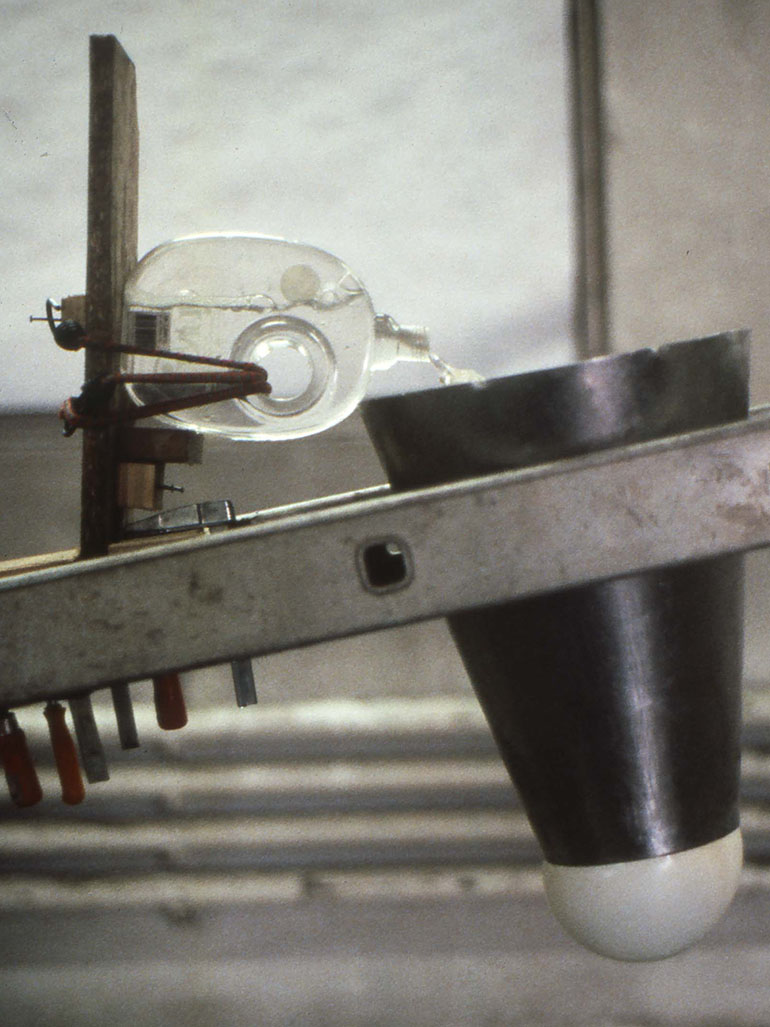

In the latter, the footage was displayed along with archival material about the Green Line. Alÿs also showed sculptures called Camguns, a blend between machine guns, cameras, and paraphernalia, created in collaboration with Angel Toxqui, using materials from Mexico City 13. The exhibition featured paintings of different places from around the world, including Jerusalem E, Bazra (2004), and Baqe (2004), which Alÿs created while he was producing Green Line.

Analysis

What Alÿs does is not usually immediately obvious, which can be said of Green Line, where no one seems to take notice of what he was doing. Even Israeli soldiers at various checkpoints barely acknowledged the lanky stranger in jeans walking with a leaky can. This is common with most of his works, which bows to iconic artists such as Gordon Matta-Clark 14 and Joseph Beuys 15.

Alÿs creates an allegory about history with his body. As he slithers along, leaking paint, the artist recreates a boundary that already exists in physical form, as a physical wall that separates Palestinians and Israelis, and as a separatist metaphor, both triumphant and oppressive.

Alÿs tends to focus on the conflicts that result from the desires of humans through examination of the intrinsic boundary and separation issues through his brief and unspoken performance rather than through propaganda slogans or verbal political narrative.

In Green Line, Alÿs connects the catastrophic situation of the region in the present moment with the historical chronicle. He awakes us, oblivious to the pursuit of action only be desire, while forgetting even what the original purpose was, in a straightforward and restrained manner.

Alÿs’s work is poetic, not less because he uses allegories and a flowing attitude in his performances. Despite his mild and natural visual activities through his performances, the artist still manages to present realistic and tragic societal issues that we face in the present. He finds his resonance in his audience’s heart, which is an essential aspect of his art.

Alÿs doesn’t take any position in Green Line. Instead, he highlights the political undertones. In a performance that blurs distinctions between documentation and artwork, he incorporates the film in his activity, archival matter on the original Green Line, as well as various interviews he recorded with modern Palestinians and Israeli and European critics.

About the artist

Born in Antwerp in 1959, Alÿs travels the world, creating artwork or interventions 16 in economic, societal, or political situations. Though not as often as his artworks, his interventions often “hit a nerve” in the local community and beyond.

Since leaving his home and formal training, Alÿs has moved to Mexico City. He has created a wide-ranging body of work that explores spatial justice, urbanity, and land-based poetics. His artwork emerges in the multi-disciplinary space of architecture 17, art, and social practice.

Throughout his career, Alÿs has employed a broad range of media, including performance 18 and painting 19, to scrutinize the tension between poetics and politics, individual action, and impotence. He said 2021:

Sometimes doing something poetic can become political and sometimes doing something political can become poetic.

Alÿs usually uses paseo (walks) 2223, which resist the domination of the common space. He reconfigures time to the speed of a walk, referring to the figure of the flaneur that is featured in the work of Charles Baudelaire and refined by Walter Benjamin 2425.

Another noticeable feature in Alÿs’s movement and mythology is cyclical repetition and return – he contracts technology and geological time using a social and land-based practice that studies individual memory and collective mythology. He also engages rumors as a key motif in his artwork, disseminating ephemeral, practice-based practice through storytelling and word of mouth.