Who is Park Seo-bo?

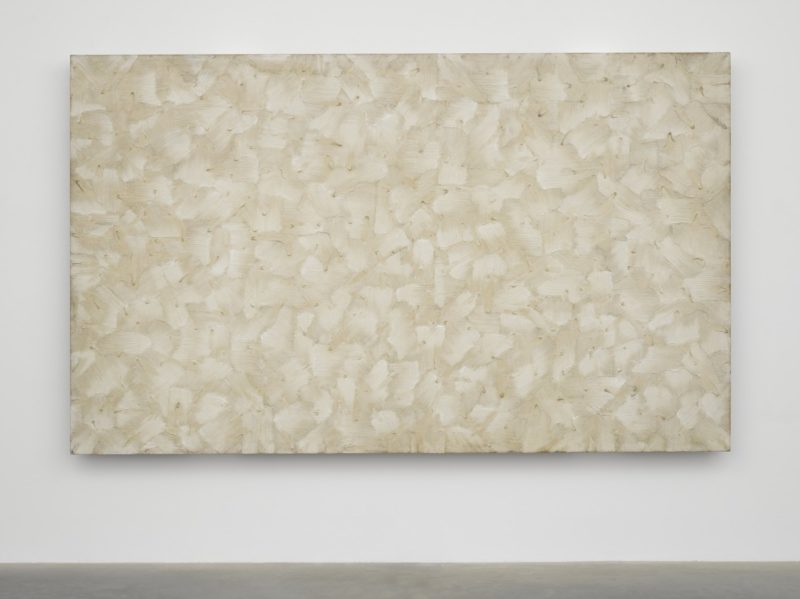

Park Seo-bo is a Korean painter and part of the first generation of contemporary artists in South Korea. Park has been prolific in his career and considered by many as the godfather of Dansaekhwa 12, Korean minimalism 34, that began in the mid-1970s in South Korea. He is perhaps best known for his series, Ecriture.

Becoming a fugitive

The artist was born in Yecheon County in North Gyeongsang when Japan had occupied South Korea 56. He was the third born of eight children. As a child, he was known as Jae Hong Park, a name he used until 1955, when he adopted the pseudonym Seo-bo to avoid forced recruitment.

During the Korean War, Park became a fugitive even after completing his military duties; the government under Syngman Rhee’s leadership reneged on its promise and planned to conscript male students during the graduation ceremony. So, Park ran away to a friend with traditional Chinese know-how to help him change his identity. He started to live a new life as a 30-year-old who always wore a fedora with a mustache.

Education & Artistic career

Park developed his visual language back during the Korean Civil War of 1950. Shortly after joining Hong-Ik University to study art, he was instead interrupted by war, forcing him to take a crash course.

I just imagine, I had to do all the things that Dada did, plus what the post-war abstraction artist did- there are some things you cannot do about in life – but I guess it was just my fate.

Park Seo Bo was committed to education, but that did not prevent him from pursuing his passion for art. He worked for the Federation of Artistic and Cultural Organization of Korea for about ten years and, at one point, served as chairman of the body.

Park organized several exhibitions including the brand-new concept called Ecole de Seoul between 1975 and 1999 as well as “Independents” between 1973 and 1980. He also organized Contemporary Art Festivals in cities across South Korea.

Ecriture

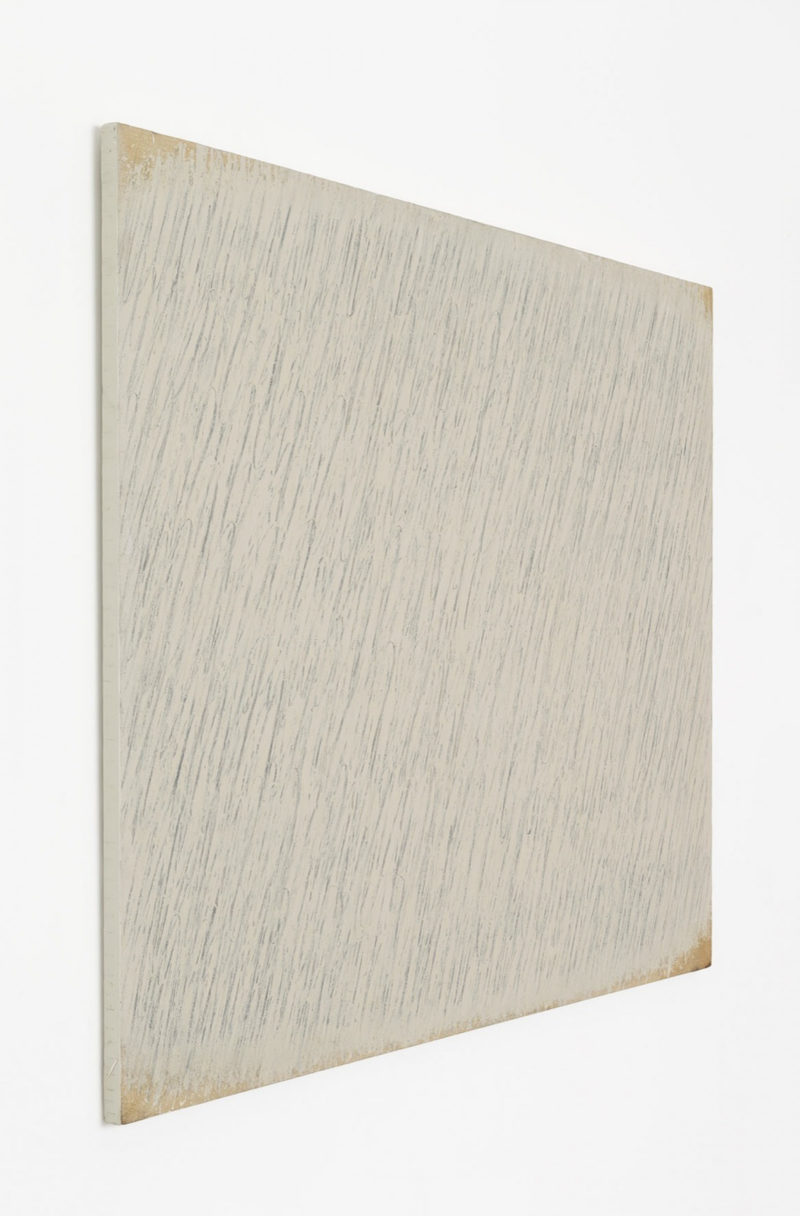

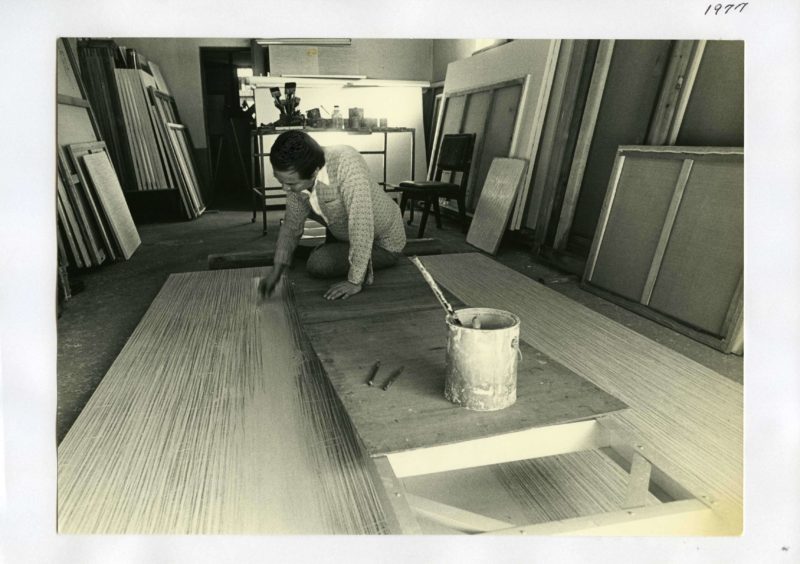

However, Park failed the election to become the chairman for the second term, and he used that opportunity out of the office to focus on himself and improve his painting skills. He had a studio in Anseong, which he had built in 1981, which is where he created his famous painting series Ecriture.

According to Park Seo-bo, the three-part series Ecriture started by clearing his mind, a connecting meditative practice of the painting process.

He said in The Korea Times 78:

Back in the 1960s, Korea was going through rapid change. Then-president Park Chung-hee was crying out for Korean-style democracy and broadcasters showed Korean images such as Saekdong Jeogori 910 (traditional Korean jacket with polychrome stripes) and Dancheong 1112 (traditional multicolored paintwork on wooden buildings). But it made me wonder what Korean is. I realized that traditional is not something you can see or touch, but it is more spiritual. I knew I had to explore the world on my own, instead of just inheriting tradition. In the course, I had to empty myself as a way to meditate and control my mind.

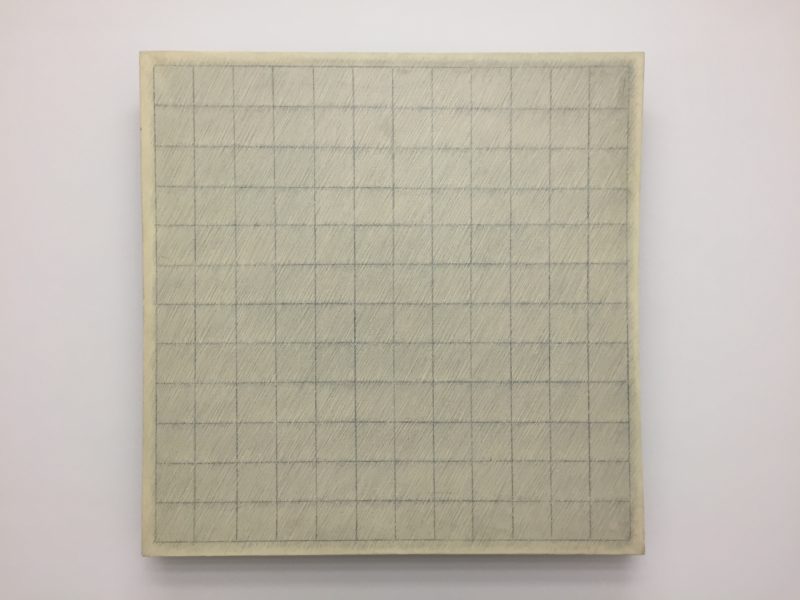

Stage #1

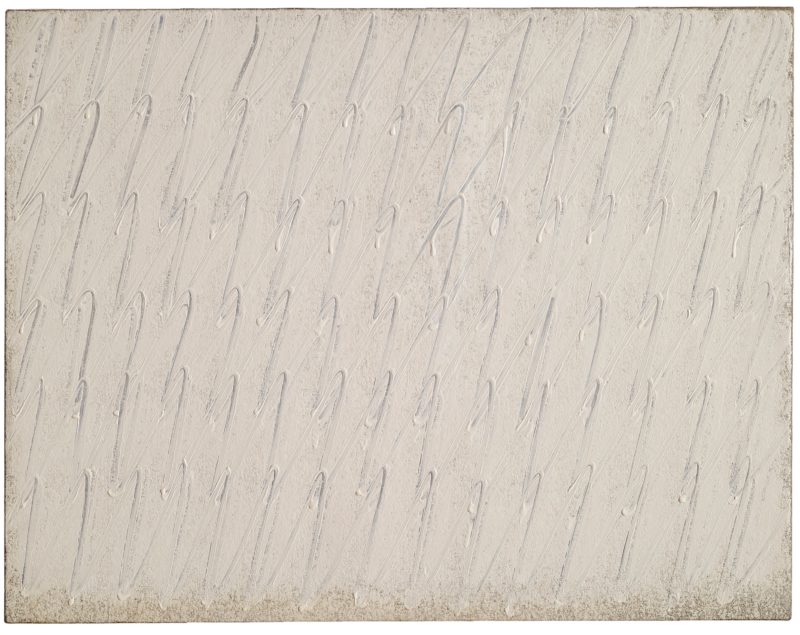

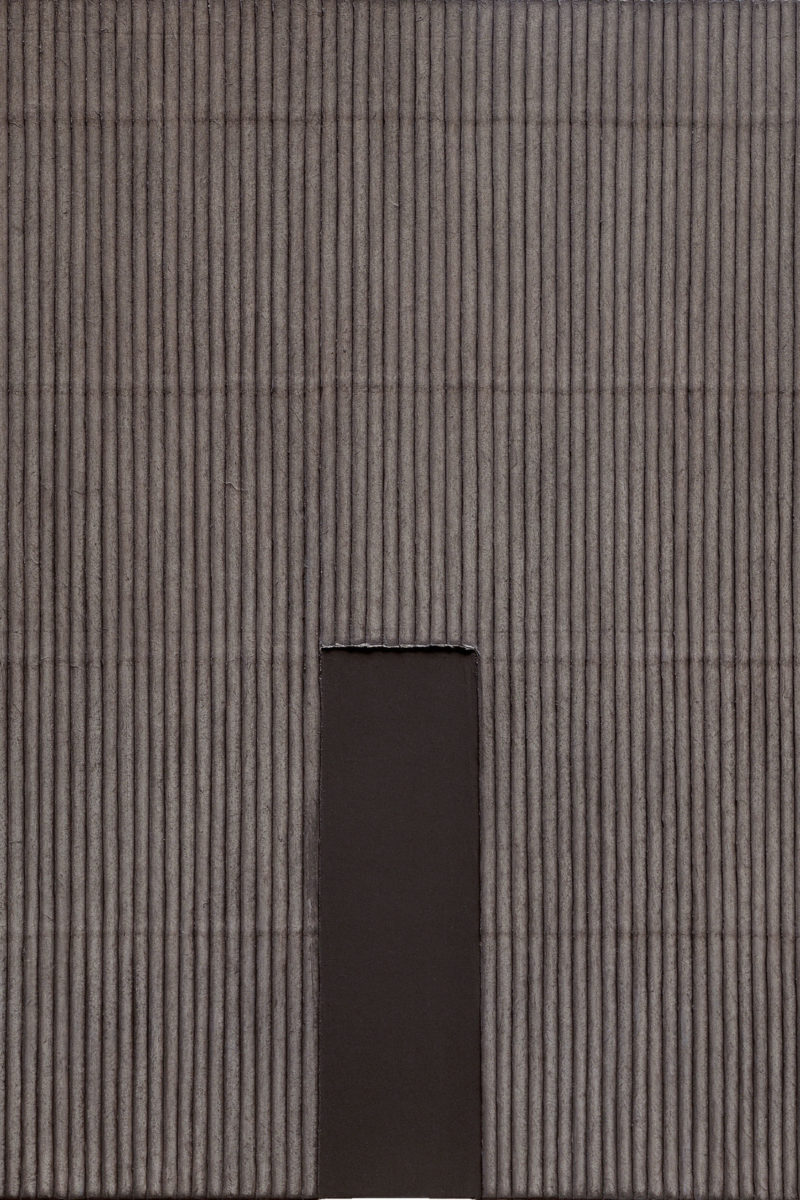

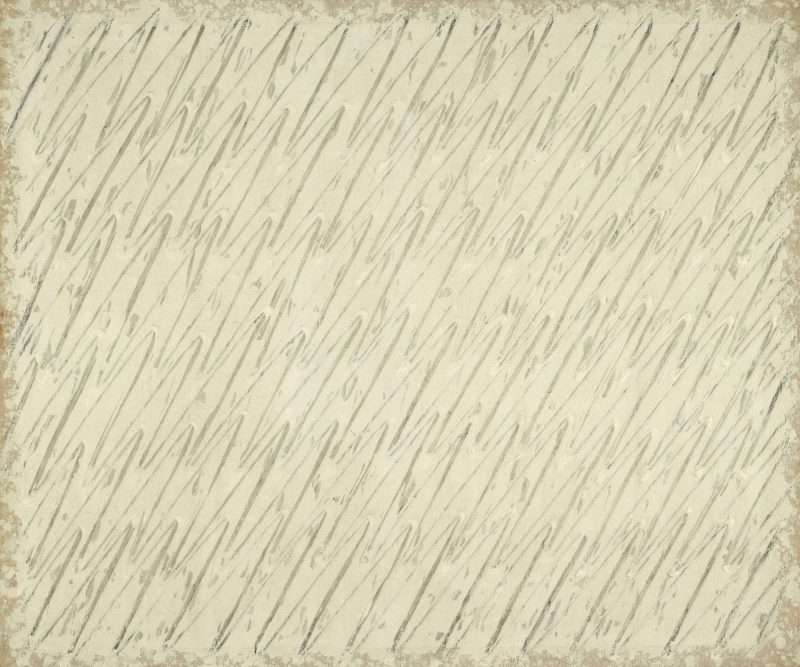

The early Ecriture paintings were influenced by his son practicing penmanship. In 1967, Park watched as his then-three-year-old son practices handwriting with a pencil on a square paper. His son was writing and erasing his work on many occasions, trying to fit letters into the grid, but with no success.

That is when Park became obsessed with Hanji 1314 due to its durability. As he tried to explore the quality of the material, he laid down the pencil and polished, scraped and pushed paint on the paper before it was dry.

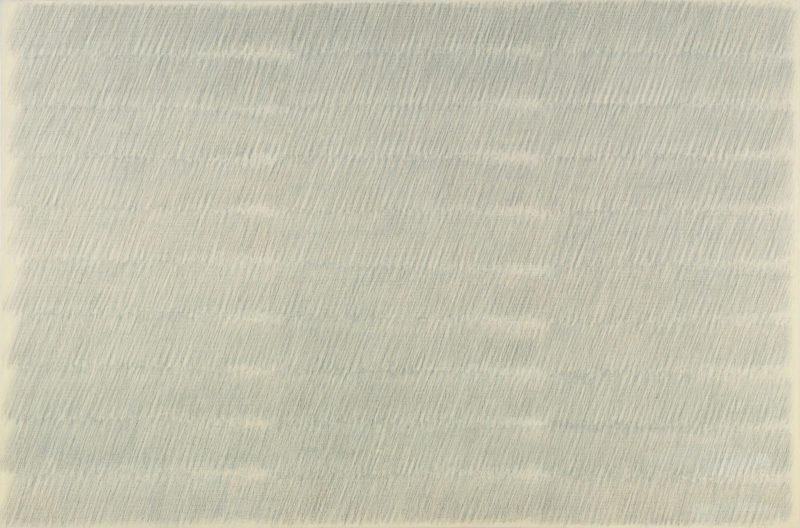

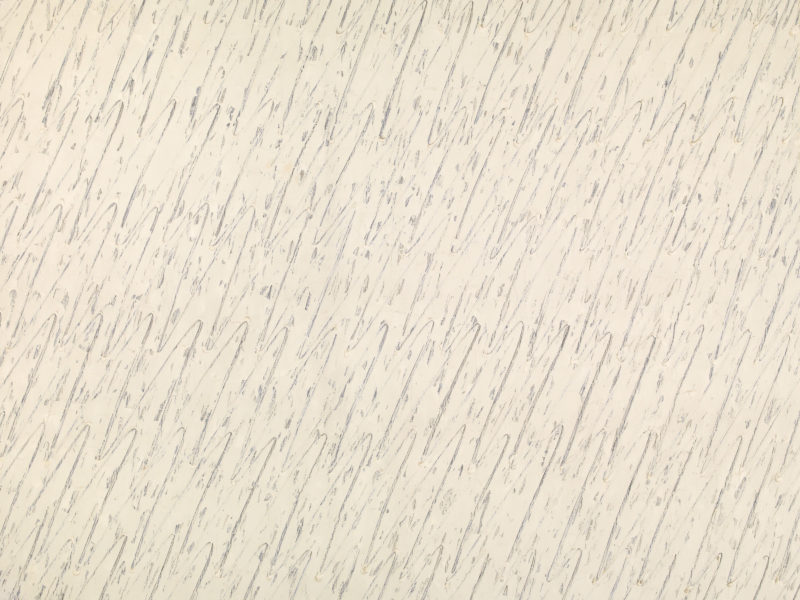

Park mainly used a pencil, which resulted in the works having a zigzag style. He created a snaky style that comes from the free movement of hands.

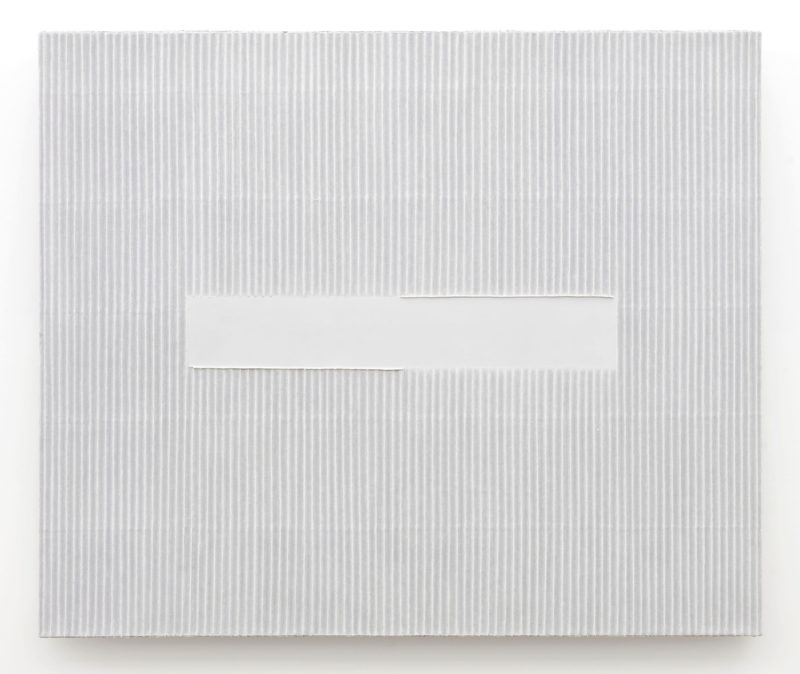

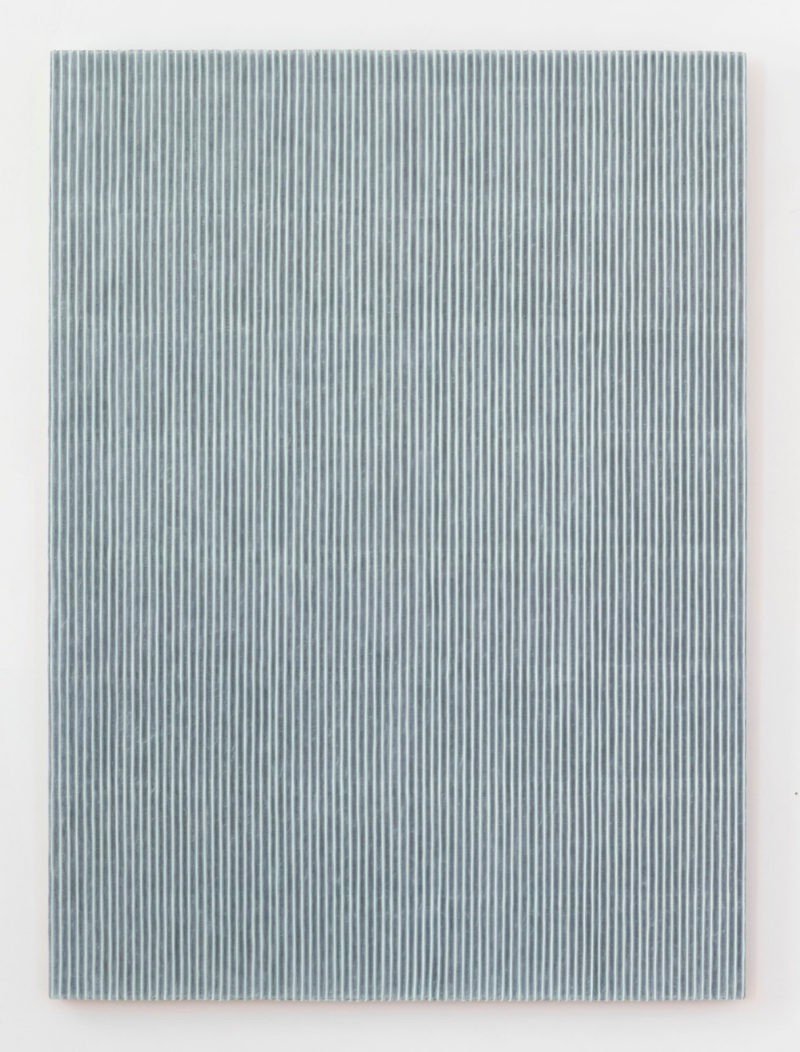

Stage #2

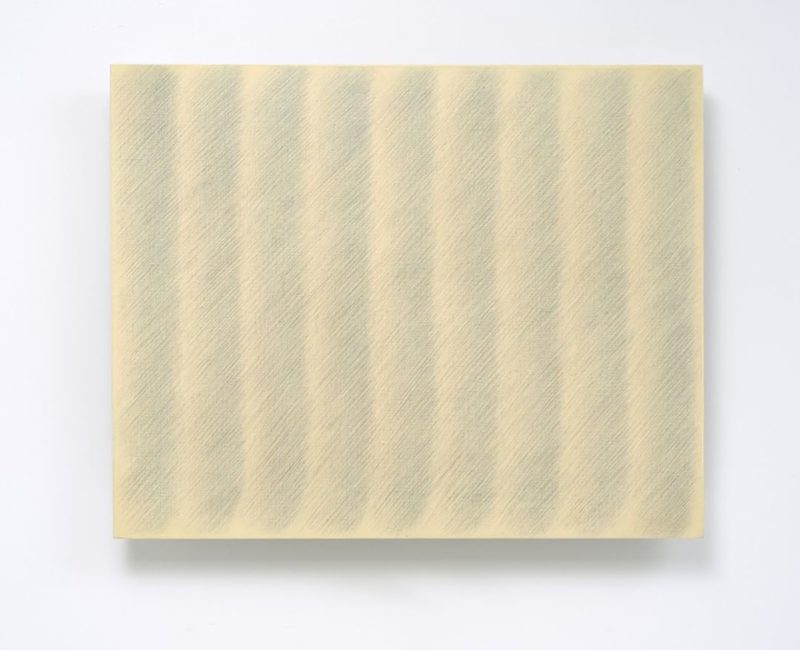

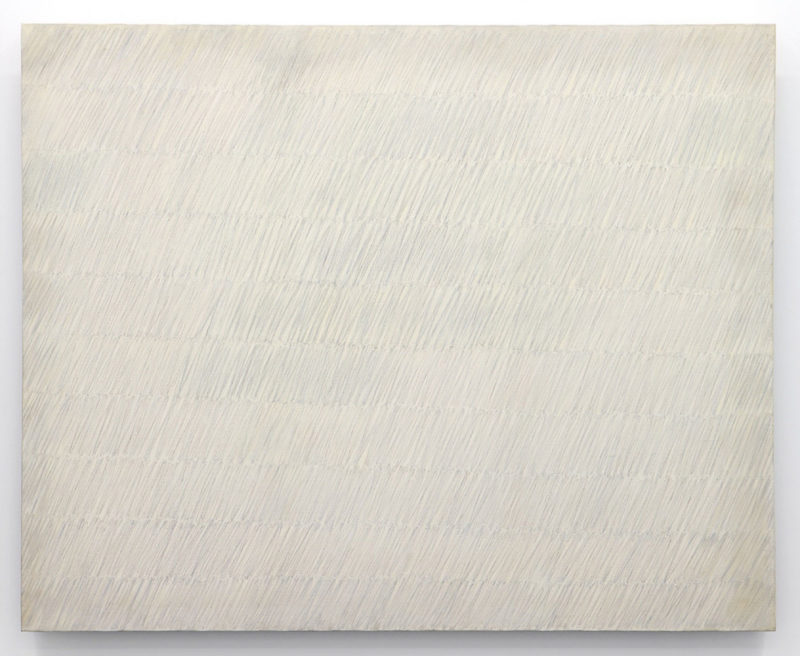

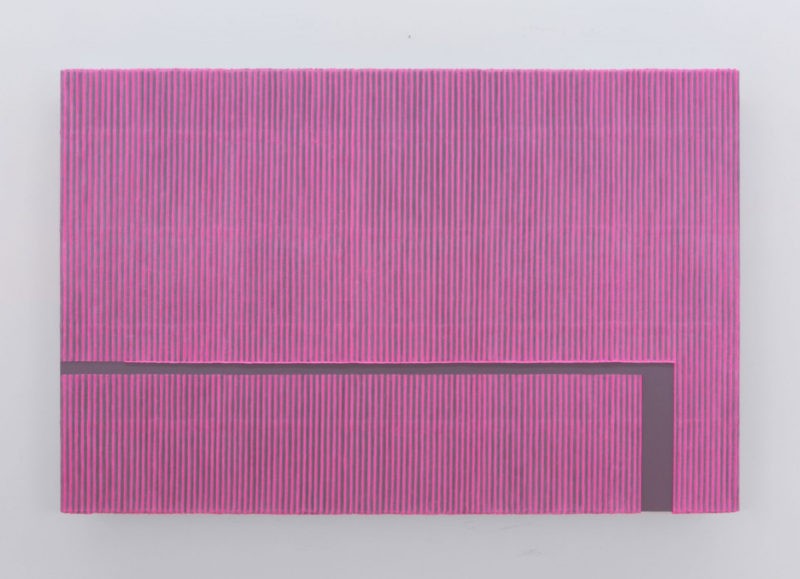

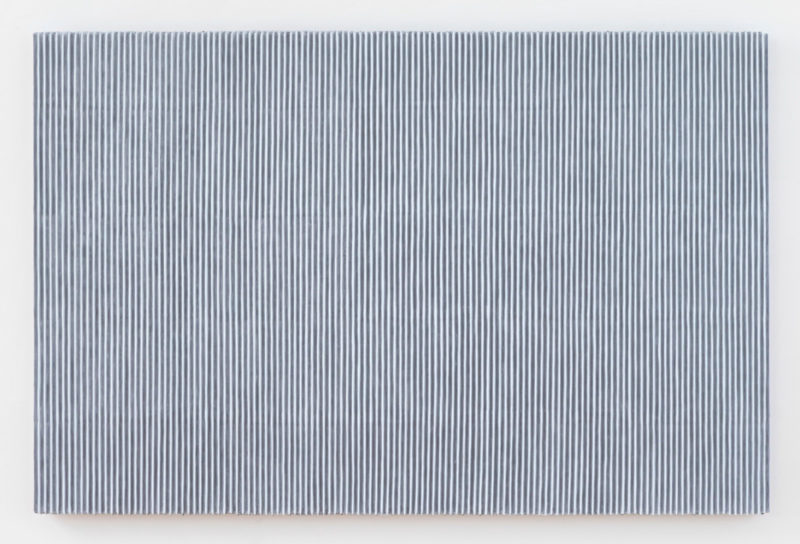

Park shifted the style of his project in the 1990s, this time creating common intervals of furrows using everyday tools, including sticks and rulers, rather than freehand movements. He also began to use lively, vita colors for the pieces of his Ecriture after his trip to Japan in 2000, where he was influenced by the colorful autumn leaves.

He says:

The autumn colors were impressive – the leaves changed colors every minute as light and wind moved constantly. I was shocked by the grandeur of nature and decided to paint the impact I received from the scenery.

Another reason to bring color to his canvas was that Park believed that art should be an instrument to heal the agony and angst of society living in the 21st century.

Stage #3

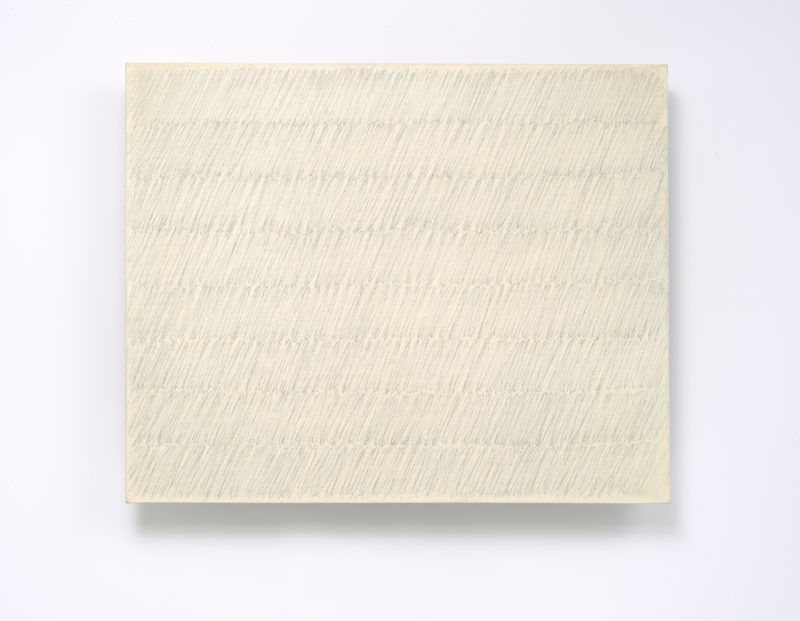

At the beginning of the 2000s, Park thought deeply about how he could adapt to the new digital age and incorporate new technology into Ecriture.

I lived for 70 years in an analog era and cannot keep up with the speed of this digital age. The art of the 20th century is the artist pouring out one’s thoughts and ideas onto the canvas. The viewers are literally getting hit by images created by the artist. It is not suitable for 21st-century art.

He believes that art should function as blotting paper, absorbing all the anxiety and anguish of viewers.

It is where the future of art should head to. It should heal the minds of people just like nature does.

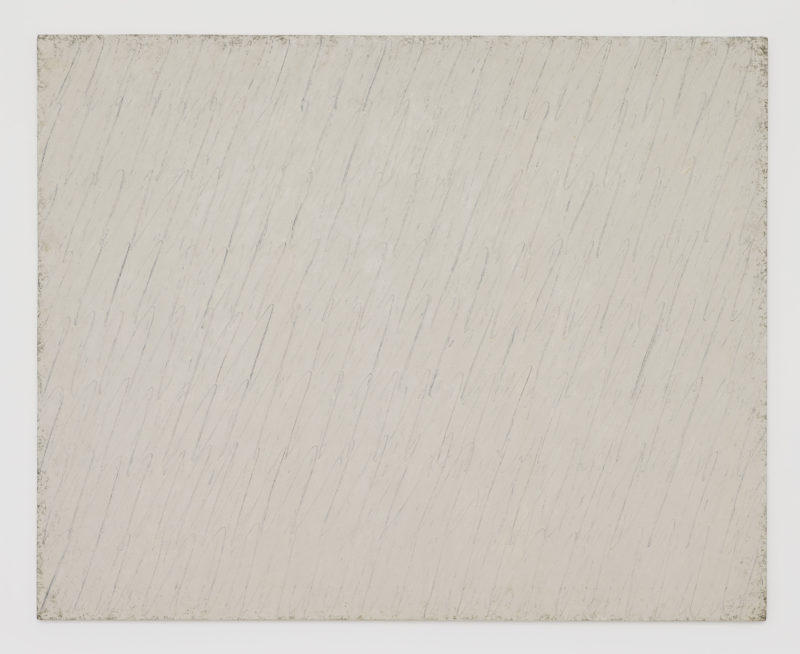

Although the colors he used for Ecriture were popular among the audience, Park ditched that style for a new one in his next stage of the project; a new pencil Ecriture style.

Speaking about his new style of drawing, Park said:

An artist must reflect on one’s own time period, not encompassing a sense of historicity.

Perhaps, that explains why the veteran artist still paints regularly, continuously refining his art.

Reception

Park’s artworks have been widely appreciated. Journalist Cheon Seung-Bok describes Park’s style in the Korean Republic (November 26, 1960) as such:

In a grammatical sense, I must say that it is hard to call his work painting, for he is a conscious action painter who tackles curious metal and chemical material and not much real paint, which is too dear for him to use. But to say that action painting like his is recondite, and therefore it is not painting, is like saying that advanced mathematics like differential calculus is not in the field of mathematics. He (Park) never buys normal canvases. Instead, he goes out to a scrap shop in an odd corner of the East Gate second-hand market, where he picks up a large patch of used ten canvases. This canvas material is usually full of dust and holes, but the price is reasonable for this artist who can hardly sell even one painting a year.

Park’s role in South Korea’s art world

While today, Park Seo-bo is a beloved figure in Korea’s art scene, he was never the gentle lamb in the herd. He was a rebellious artist and a revolutionary figure of abstract art in the region. For example, in the 1950s, he won several prizes at the National Art Exhibition of Korea, a prestigious award for aspiring artists. However, in 1956, he blasted the institution and boycotted it all together.

Seo-bo Art and Cultural Foundation & Other

Park founded the Seo-bo Art and Cultural Foundation in 1994 in Seoul and remained its president up to 2014 when his son took over. He recently had his only second retrospective exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, held in Seoul in 2019. Today, Park lives at his new home in Yeonhui-dong, Seoul, with his wife and his second son. He still works on paintings and strives to be active against his aging and chronic diseases.

Video: Park Seo-Bo documentary

Setbacks & Motivation

In 1996, over 150 pieces from the series were burnt out in a fire accident at his Anseong studio. The incident affected Park significantly. He never revisited his studio until his wife sold it in 2006. Park had a new studio where he worked from in Sungsan-dong, Mapo-gu, Seoul, in 1997. He also used that building as his home from 1999.

What keeps him going?

When asked about what still drives him daily, he said in The Artro 1516:

Let’s just put it this way: I feel ill at ease when I don’t paint. It is as if I am re-affirming my own vitality through painting. Even though painting can be torturous when I am feeling mentally blocked, I’m never as happy as when I am painting. I get anxious when away traveling for a few days or when I take a bit of a break. Whenever I return, I rush back to the studio and pick up the brush again, no matter how tired I might be. From my twenties until late November in 2009, I spent 14 hours a day painting. When I was a college student, we didn’t have the proper equipment to make art. I stayed late after classes to work; we were in the middle of a war, so there would be several grades all grouped together in a single classroom. I would work until late in the evening, then sweep the floor and tidy up the classroom so I could collect discarded pencil tips…