About Andreas Gursky

Andreas Gursky 1, born in 1955 in Leipzig, Germany, is a renowned photographer who uses colorful, large-scale 2 depictions of modern life. Living and working in Düsseldorf, Germany, he represents a revaluation of realism within contemporary photography through conceptual staging and digital image editing. The German photographer popularised photography focusing on day-to-day human activities in commerce, sports, leisure and others. His trademark photos show large formats of stock exchanges, ports, concert arenas, race tracks and other areas that hold human activity. The point of angle is usually elevated to take in as much area as possible.

Early life & influences

Gursky studied photography at the Folkwang Academy in Essen during the 1970s. He started experimenting with a 4×5 inch (10.2×12.7 cm) camera, which was at odds with the photography of these days. His early work was initially strongly influenced by the Becher 3 aesthetic. Later, his style became known as uniquely ‘Gursky’ as he slowly shifted away from their philosophies and produced large-format color photographs with unreal documentation of details.

His work matured quickly in the 1990s after he started to focus on scenes and places depicting the international sentiment of modern society. He was later known for employing excessive detail in his work, as can be seen in his photographs like the May Day series and 99 Cent. Today, his pictures continue to represent scenes occurring in instantly recognizable urban settings and heavily computer-rendered images.

Gursky pushed large-format photography to new heights. By the 1980s, he was printing on commercial photography paper using the largest print paper available. He combined print papers to make the photos even larger. He was the first photographer to produce prints larger than 6×8 feet (1.8×2.4 m).

Recurring topics

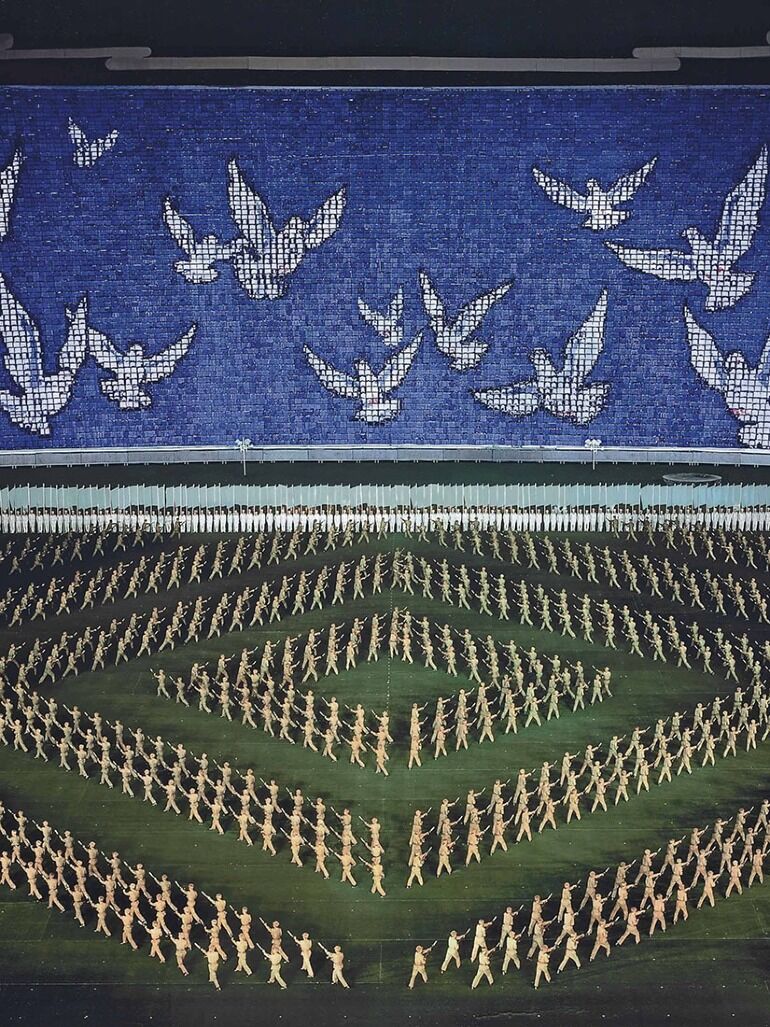

The spectrum of Gursky’s work includes topics such as architecture, landscape, interiors, as well as large events with huge crowds such as The Mass Games of North Korea 4 or his famed series of photos of stock exchanges throughout the world 5. By doing that, he covers aspects of modern life in work, business, and social life.

In his own words

It is not pure photography, what I do. All my pictures are based on a direct visual experience from which I develop an idea for a picture, which is subjected to testing in the studio and eventually worked on and precised at the computer.

Selected works

99 cent, 2001

99 Cent represents the quintessential Andreas Gursky photograph. The image comprises several pictures of products taken in a 99 Cents Only Store in Los Angeles and then stitched together to form a single large-size digital image.

Another thing that cannot be missed is the heads of shoppers going about their businesses, looking for what they need. While the photograph shows us what we see every day in retail stores, it shows us what we don’t see every day. When we visit a supermarket, we don’t get an opportunity to take in what we see in the 99 Cents photograph. Instead, we are always in a hurry to pick what we want and leave the store, just as the busy heads of shoppers can be seen floating anonymously above the products.

99 cent has a deeper meaning than just an image of a typical store. Gursky tries to show the audience what they are up against. This, to him, is the world that we have created ourselves, yet we are ignoring it. Despite its somewhat rigid composition, the photograph, with its unending detail, is a visual assault. 99 cent is one of the most expensive modern photographs ever sold.

Amazon, 2016

Amazon (2016) indicates just how talented Andreas Gursky is by turning an Amazon depot into art. Gursky wanted to photograph a high-rack room packed with books at a warehouse in Phoenix, Arizona before the idea of taking pictures of the Amazon distribution center came to mind. At first, the warehouse’s security could not allow him to use the truck he needed, but eventually, the company’s CEO, Jeff Bezos, was convinced.

Amazon, 13 feet long and 8 feet tall, is a single large-scale image showing unrecognizable patterns of modern mass consumption and the distribution of goods. The artist managed again to observe detail in taking this picture as everything is equally in focus. The rows of products invoke the elements of the art of the 19th and 20th centuries, including geometric and pointillism.

Amazon is very different from the previous work 99 Cent, though they are all pictures of the same things. In 99 Cent, we are introduced to something we are familiar with, while in Amazon, we are looking at an unfamiliar space.

Formula 1, 2007

In the four Formula 1 series, Gursky captured busy mechanics and technicians in bold team colors surrounding Formula 1 vehicles in the pit stop, above which spectators are staring down. The photographs are one of the few in which the artist used Photoshop to reorganize the fragments of the picture. The series, created in 2007, focuses on the frenetic activities at the Formula 1 pit stops, capturing the crucial moments that could influence the driver’s career.

At a glance, one may think that the spectators in both images are identical. However, when looking keenly, it can be seen that the appearance of the figures varies, especially in terms of color. The four-image series is not a single image like the 99 Cents and Amazon but slightly manipulated photography comprising elements from Formula 1 races worldwide, including Sao Paulo, Monte Carlo, Shanghai, and Istanbul. While the pit stop activities usually take place within only twelve seconds, Gursky portrays the figures in the images in great detail. There is no element of motion as though he had asked them to pose for a shot in the middle of a Formula One track ballet.

One thing viewers might miss in Formula 1 is the inclusion of an attractive grid girl placed directly in the middle of the photograph. One distracted racing team member turns to stare, oblivious to the activities behind him. While the humor can easily be missed, Gursky tries to make it less obvious to the viewer’s eyes. The photos are enticing, making it easy to ingest every emphasized detail. The artist uses contrast to achieve the hypnotic effect. Measuring a whopping 222 centimeters by 608 centimeters, Formula 1 is the largest photograph by Gursky to date.

Bahrain, 2005

Bahrain 1 is a photograph of a Formula 1 circuit taken in 2004 but created in 2005. The racetrack was from the annual Formula 1 race completed in 2004, and Gursky took the shot from a helicopter. He eventually manipulated the photo, as he did in Formula 1, using Photoshop.

Bahrain 1 shows a snaky Grand Prix Circuit making its way through the desert 6 landscape. Black tarmac tracks form a strong dissimilarity with the light brown desert sand surrounding them. There are no single figures shown, cars or people, in the image, although beyond the racetrack, one can notice a long straight grandstand with a white roof.

In Bahrain 1, Gursky reinterprets the landscape by reversing the typical sky to land ratio. The landscape is stretched up towards the plane of the picture, leaving just the uppermost portion of the entire photograph for the sky. The flatness and of the opaque racetrack and the desert landscape allows for completely no gradation in the tone. The result is a composition that is quite amazingly painterly. The spinning forms of the circuit appear to be calligraphic brushstrokes of black paint on a blank canvas. But when one views it closely, they will see the defining features of the racetrack. Just like most of Gursky’s works, in Bahrain 1 he represents the human presence within the natural setting in an optically compelling way.

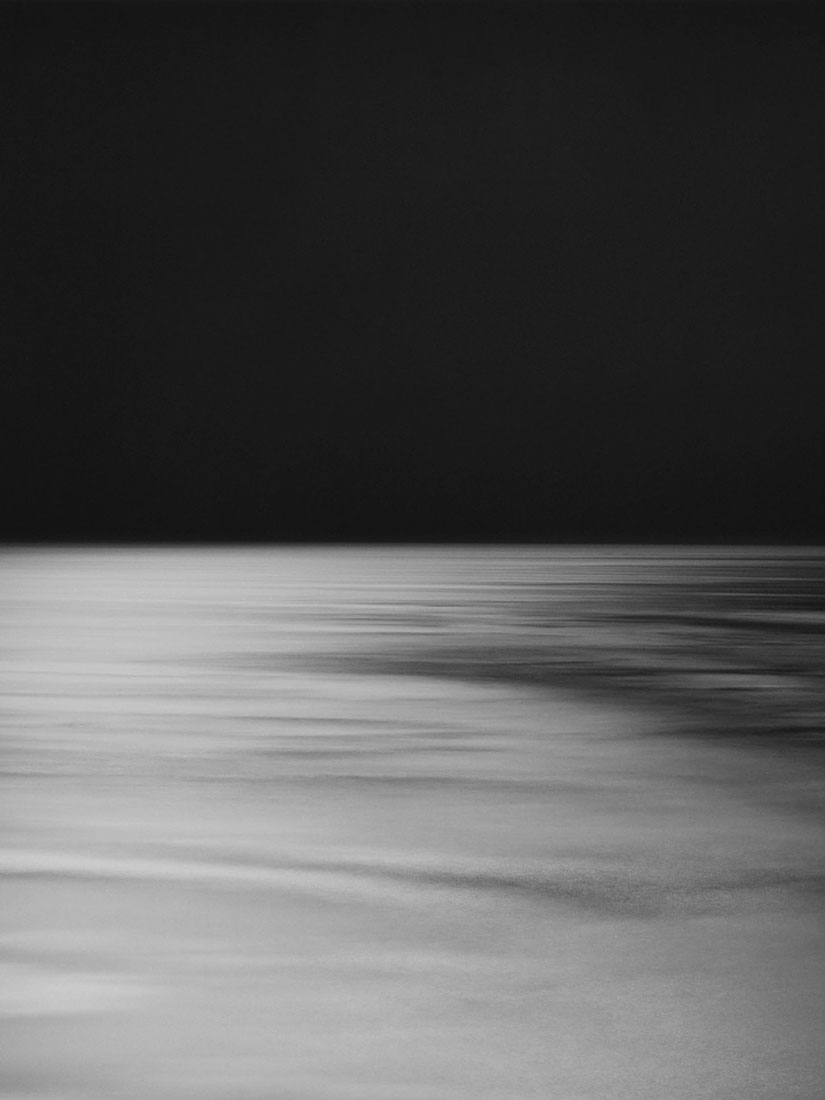

Rhine II, 1999

In this photo, Gursky combined large-scale photography and digital manipulation to create an entirely new section of the River Rheine. It is a 5 x 10 feet (1.5 x 3 meter) photo that shows a high color landscape free of human presence and industry. Gursky achieved this by combining several sections of the river 7. This photo became the most expensive ever sold at an auction, fetching $4.3 million in 2011.

Rhine II is a photograph of the Lower Rhine River that flows from Bonn German to Hoek van Holland. In the photograph, the river flows straight across the field of view, through flat green fields and under a cloudy sky. The artist removed irrelevant details such as factory building and dog walkers, using digital software.

Gursky said of Rhine II, “Paradoxically, this view of Rhine cannot be obtained in situ, a fictitious construction was required to provide an accurate image of a modern river.”

In 2011, the Rhine II fetched £2.7 million at an auction, making it the most expensive photograph ever.

Commentator Florence Waters has described the art as a “vibrant, beautiful and memorable – I should say unforgettable – contemporary twist on the romantic landscape,” and by Maev Kennedy as “a sludgy image of the grey Rhine under grey skies.”

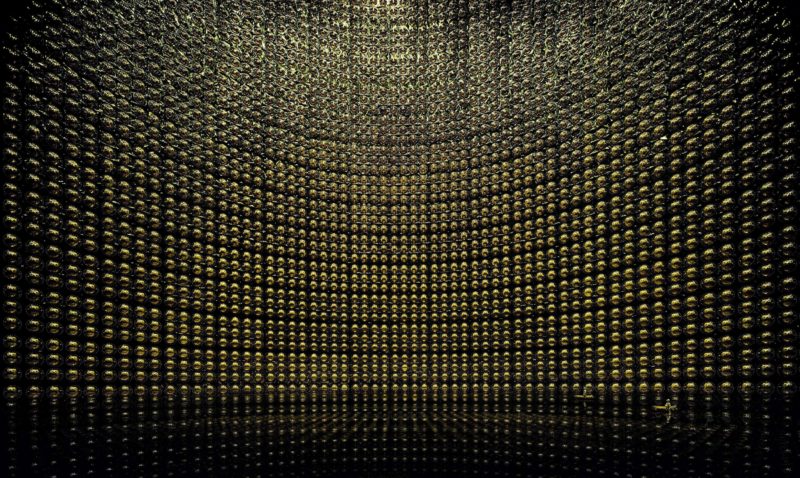

Kamiokande, 2007

Kamiokande was taken in 2007 under Mount Kamioka in Japan. It is a supernatural photo of the neutrino observatory that aids the Super-Kamioka Neutrino Detection Experiment. The whole photograph comprises thousands of shining gold spheres that create the walls of the space. The orbs attract lights on their surfaces from the above. It then reflects it onto the surface of the obscure water that forms the floor of the observatory. In the bottom right-hand of the photograph are minuscule figures in sterile lab outfits standing in hygienic inflatable rafts. After taking the photograph, Gursky simulated it with digital editing to exaggerate the photo and make viewers see just how jaw-dropping and striking the photo location is.

The shot presents a brilliant balance of reflection between the mirror-like water surface and the shiny metallic orbs. In creating this work, Gursky complied with the traditional landscape rules using an utterly untraditional subject. The themes in Kamiokande are similar to the 17th-century paintings by Dutch artists and contemporary works by Ansel Adams. However, Gursky has included an endless stretch of polished artificial orbs and a stripe of water. In this case, humans manipulate nature, as is the case with the real Kamiokande. This goes against the conventional theme of the authority of nature over man.

Kamiokande shares some similarities with Andy Warhol’s work 8 in the sense that it also employs the use of repetition and simplicity. Another resemblance with Andy Warhol is that Gursky also believes that art is absolutely everywhere and in everything. The exact use of the real observatory is unknown to many, Gursky managed to present the space with an awe-inspiring optical allure that immediately renders the question moot.

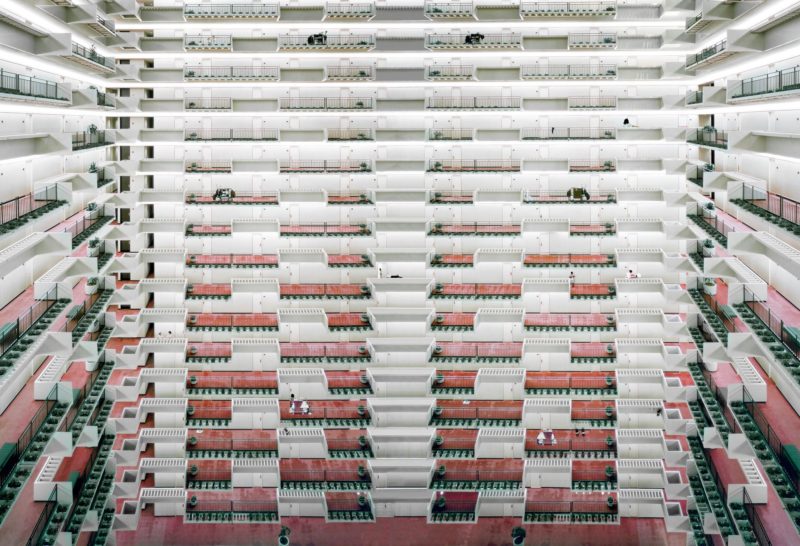

Atlanta, 1996

Atlanta is another manipulated photo, like other works by Gursky. In this photograph, he has employed digital tools to merge two dissimilar viewpoints of the hotel designed by John-Portman. The image comprises shots taken at the Atlanta Hyatt Regency’s lobby. They are made from the same vantage point but at 180 degrees from one another. Gursky fused the opposite ends of the same vestibules, creating a back wall that was never there. Just like Bahrain I, Atlanta also looks like an abstract painting. On a thematic level, this work is pretty much like the majority of Gursky’s works.

This photograph visualizes a world of global migration and flow. A space in which leisure, labor, and travel are evenly interrelated, while humans seem to be channeled as though they were materials being processed inside a giant machine. Although the photo appears cool and deadpan, the photograph seems gloomy in the sense of its formal qualities.

Atlanta is perhaps one of the strangest works made by Gursky. Superficially, it appears interactive like most of his works, but when one looks at it for some time, they might begin to mistrust their own perception. The viewer can understand that the landscape represented in the image is unnatural. Whatever reality it tries to express, what the viewer sees is a completely different world from what existed before the lenses of the artist. When the audience notices the digital manipulation of the image, the view becomes even cannier. What is in front becomes physically impossible because it comprises more than twice the standard of human vision range. But, still, it appears similar to our normal field of view.

In Atlanta, the reality is rendered both strange and familiar. Therefore, despite its detail and clarity, the photograph does not focus on its documentary features. Instead, it emphasizes its digital manipulation, sowing seeds of doubt about its true nature and the viewer’s ability to understand the objective world.

Montparnasse, Paris, 1993

Paris, Montparnasse is an epic urban panorama and one of the most definitive and spectacular works by Andreas Gursky. The piece once again displays the artistic credentials of Gursky in the photography medium. It is not the first time Paris allures artists, as many before Gursky also fell in love with the city.

Gursky started taking shots of the City of Lights in the early 1990s, drawing inspirations from the architectural design of the Immeuble d’habitation Maine-Montparnasse II. The building was designed by architect Jean Dubuisson and built between 1959 and 1964. The structure consists of 750 apartments that accommodate up to 2,000 residents, making it the single-largest residential structure in Paris.

Paris, Montparnasse is the first image of all of Gursky’s creations in which he used digital manipulation. He would go on to use this practice repeatedly in some of his works, including <em<Formula 1, Bahrain 1, and Atlanta. The artist was quoted saying: “Since 1992 I have consciously made use of the possibilities offered by electronic picture processing to emphasize formal elements that will enhance the picture or, for example, to apply a picture concept that in real terms perspective would be impossible to realize.”

The photograph is an elevated view of a high-density apartment building in Paris. The dimensions of the print are 7 x 13 feet (2.1 x 4 meters), creating a panoramic effect that captures the ground, building, and sky. The interesting thing is that Gursky did not capture the edges of the building. The overall effect is one of isolation and alienation of the inhabitants of the high-rise, which is a paradox.

1990s

Gursky says the four shots of the Salerno port in Naples were done by whim. The warm sunlight invited him to shoot a few photos. Interestingly, there were no people in the photos, only numerous new cars, shipping containers, berthed ships and the background of the sea. He says this was the turning point at which he discovered the powerful effect of shooting great scale and sharp accuracy.

Like much of Gursky’s oeuvre, this piece plays with the viewer’s sense of scale, offering a perspective that is both intimate and detached. The photograph, taken in Salerno, Italy, showcases Gursky’s fascination with human-made environments and their interaction with the natural world. The use of color, light, and shadow create a sense of depth and dimensionality that is almost palpable.

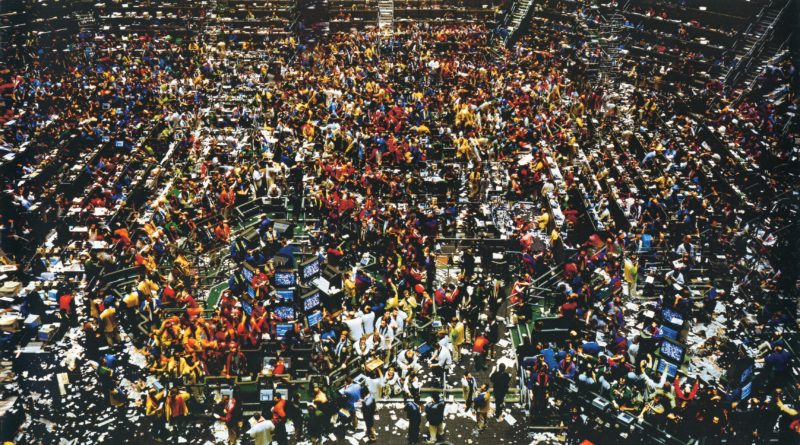

In this photo, Gursky captures the frenetic activity of the Chicago Board of Trade perfectly but without any point of focus. There are movement and detail all over the photograph, which also creates a feeling of more activity outside the photo. Chicago Board of Trade II explores human activity within the confines of modern capitalism. The photograph, capturing the frenetic energy of traders at one of the world’s oldest futures and options exchanges, is a symphony of chaos, order, and human endeavor.

At first glance, the viewer is confronted with a sea of figures, each engrossed in their own world of transactions and trades. The sheer scale of the image, a hallmark of Gursky’s work, overwhelms and invites closer inspection simultaneously. As one delves deeper, individual stories begin to emerge from the collective, a testament to Gursky’s ability to capture both the macro and the micro in a single frame.

The use of color is particularly striking. The muted tones of the trading floor contrast with the vibrant hues of the traders’ jackets, creating a visual rhythm that mirrors the ebb and flow of the market. The elevated perspective, another Gursky signature, lends an almost god-like view of the proceedings, prompting reflections on the nature of commerce, human ambition, and the systems we create and become ensnared by.

In Chicago Board of Trade II, Gursky offers more than just a snapshot of a place and time. He presents a meditation on modern life, with all its complexities, challenges, and contradictions.