Why did Félix González-Torres install candy in museums?

Félix González-Torres 1 has created nineteen candy pieces that were featured in many museums around the world. Many of his works target HIV, a topic of a serious nature, one that is still unfortunately often taboo in mainstream society. It takes the topic from the shadows, where individuals still cringe, averts their eyes, and lays it on the table for discussion and contemplation.

Why is his work still relevant?

While there has been much development and change since the 1980s and 1990s, there has been no cure and there has remained a stigma attached to the disease. Treatment allows individuals with HIV to live long and fairly normal lives. However, much more work is still needed in the area, and there is a need for unstigmatized conversation.

His works say so much and are absolutely just as important today as in the 1990s. If you ever have the chance, these pieces are a must to see.

About Félix González-Torres

González-Torres created Untitled in 1991 around the time Ross, his boyfriend, died from AIDS. A few years later, he also dealt with the virus and died in 1996. But his work remains a clear testament that things can change and we have to do everything in our power to keep people healthy and away from health issues. He managed to successfully capture all of this in his comprehensive and downright emotional works.

Selected works

Untitled (Placebo), 1991

In Untitled (Placebo), González-Torres put a plethora of different types of blue candy on a showroom floor, and all of them were wrapped with blue cellophane. Visitors were encouraged to pick those pieces from the floor and eat them as they see fit. As you can imagine, the candy pieces started to disappear and that left lots of empty space. But this was obviously a representation of something. In this case, it showed a massive amount of pills that ill patients take during their life.

It shows that regardless of how many pills you take, health problems will still catch up to you and that’s why you need to do everything you can to stay away from those problems from now on. Simply put, death doesn’t really care who you are, what statute you have or anything like that, and anyone can deal with illness.

But technology evolves and we are using it to treat illnesses. Before researchers created HIV treatments, people with HIV or AIDS had either little or no hope to recover. But these things went away now that we have a way to deal with this.

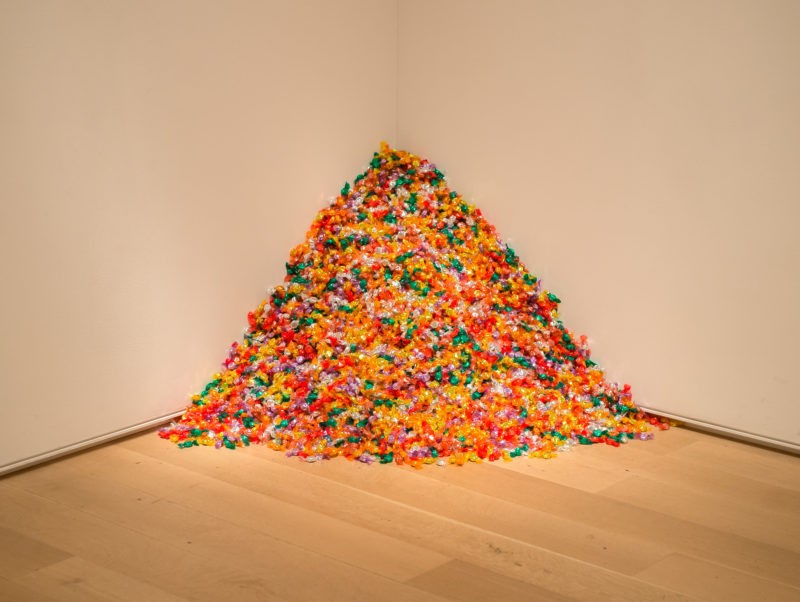

Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991

The approximate 175 pounds of candy that make up the work resembles the 175-pound body of Ross Laycock, the artists’ boyfriend who died of AIDS in 1991. As each person takes a piece of candy, they in turn act as the AIDS virus depleting Ross’ body, piece by piece taking it away until there is nothing left. Félix González-Torres, who dedicated his artwork to the one he loved and lost, died in 1996 of AIDS.

His work doesn’t only represent the disease and its depletion on the body, but it represents the love between the person suffering from the disease and the person who is there to support them and suffer with them. The sweet candy, in and of itself, is a representation of love. If you think about giving candy to a loved one on valentine’s day, sweets in a box with flowers on mother’s day, candy has long been tied to affection and love. While the candy is eaten, while the body begins to disappear, the love remains.

Untitled (Lover Boys), 1991

The weight of this pile of candy is 161 kg, the ideal joint weight of the artist’s and the artist’s partner’s bodies. His partner, Ross Laycock, was dying of AIDS as the work was done. Viewers are encouraged to take away candy from the pile, which then gets refilled by museum staff – symbolizing loss and eternity.