Introduction

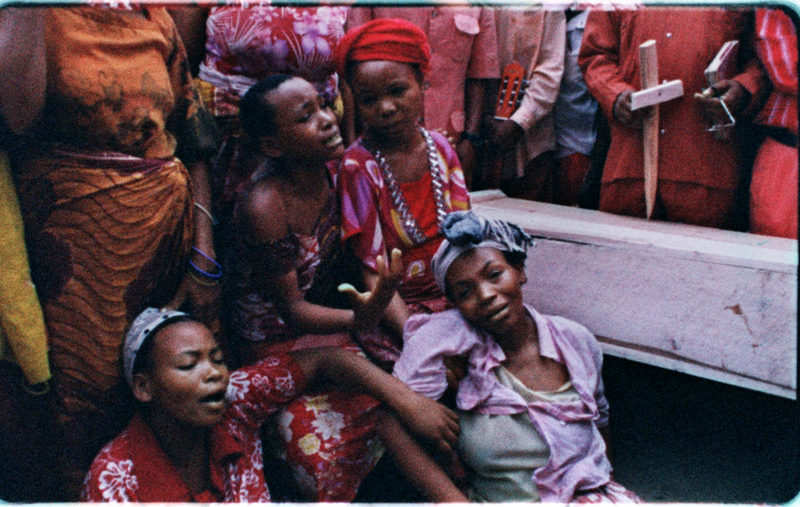

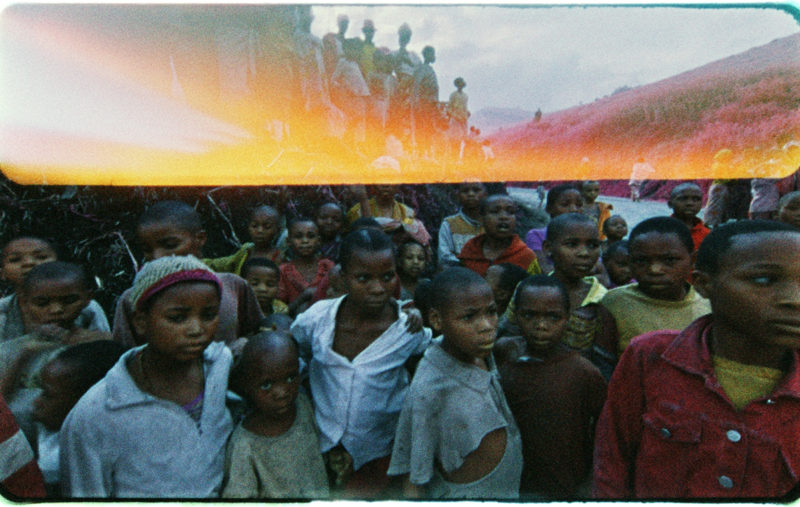

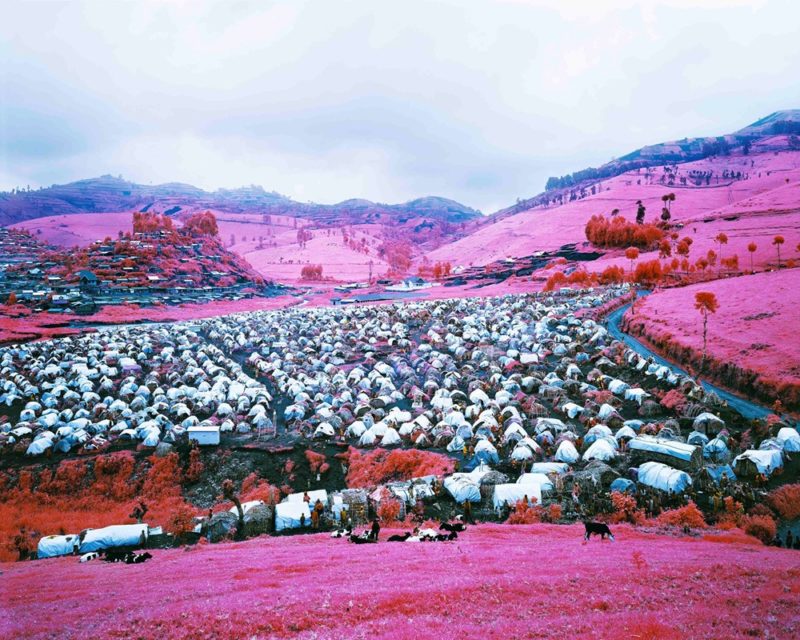

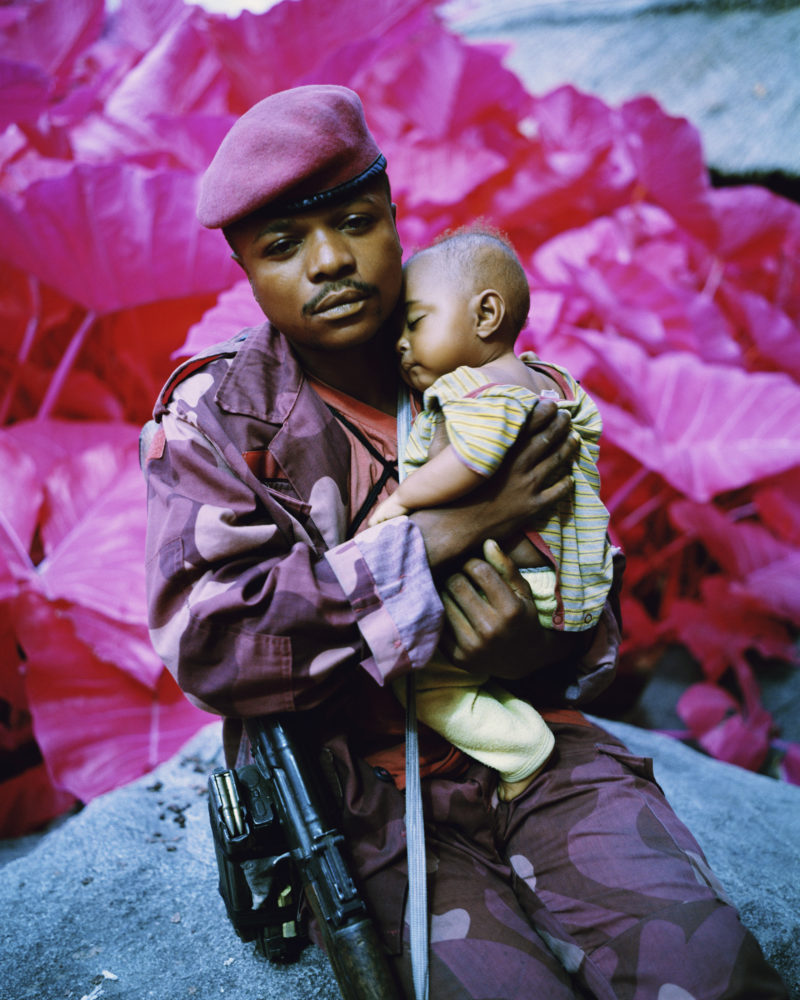

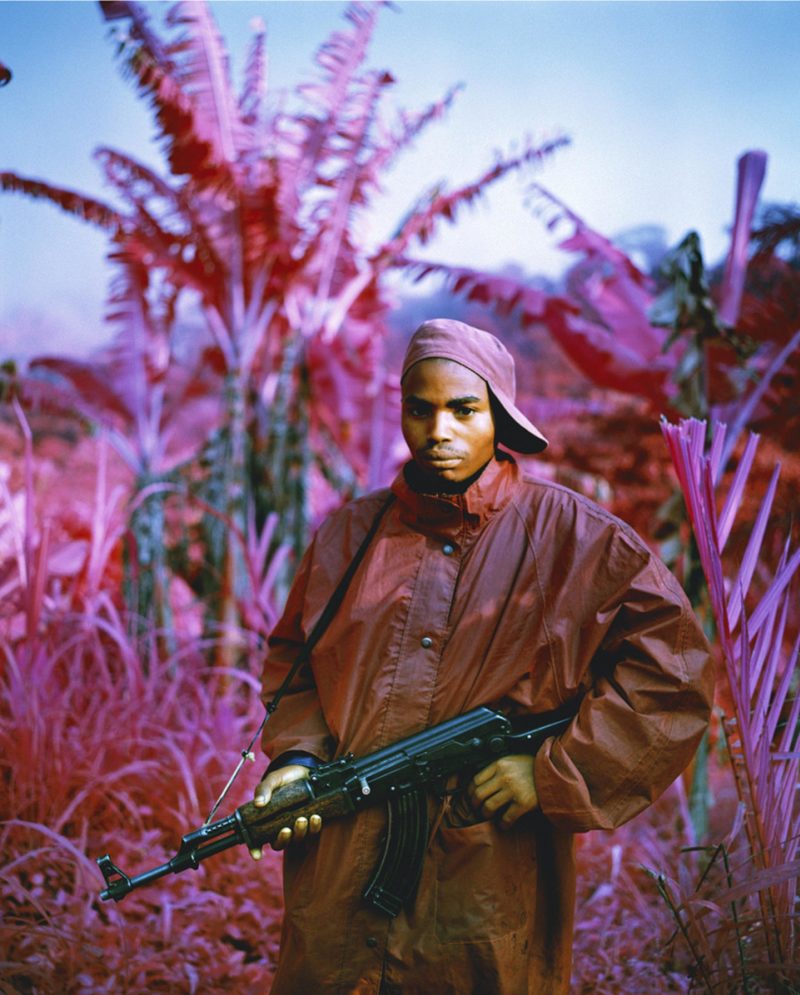

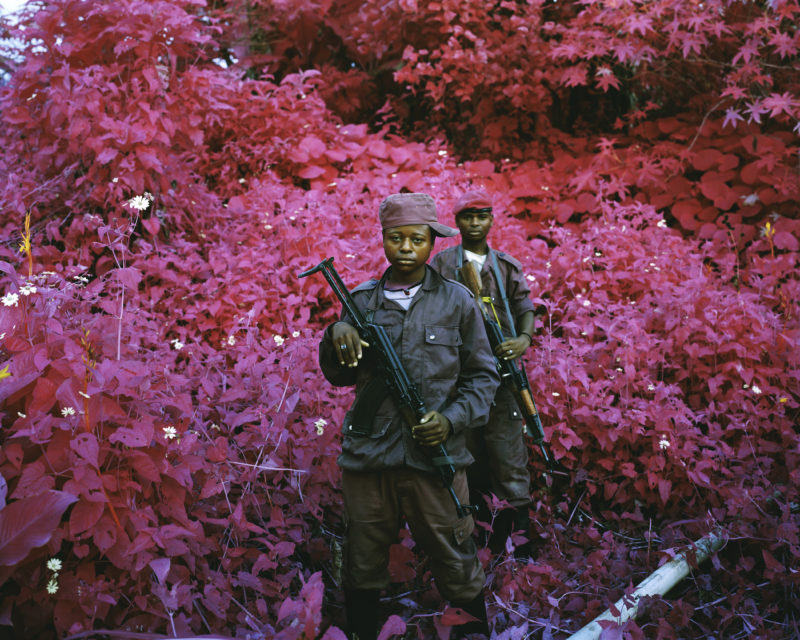

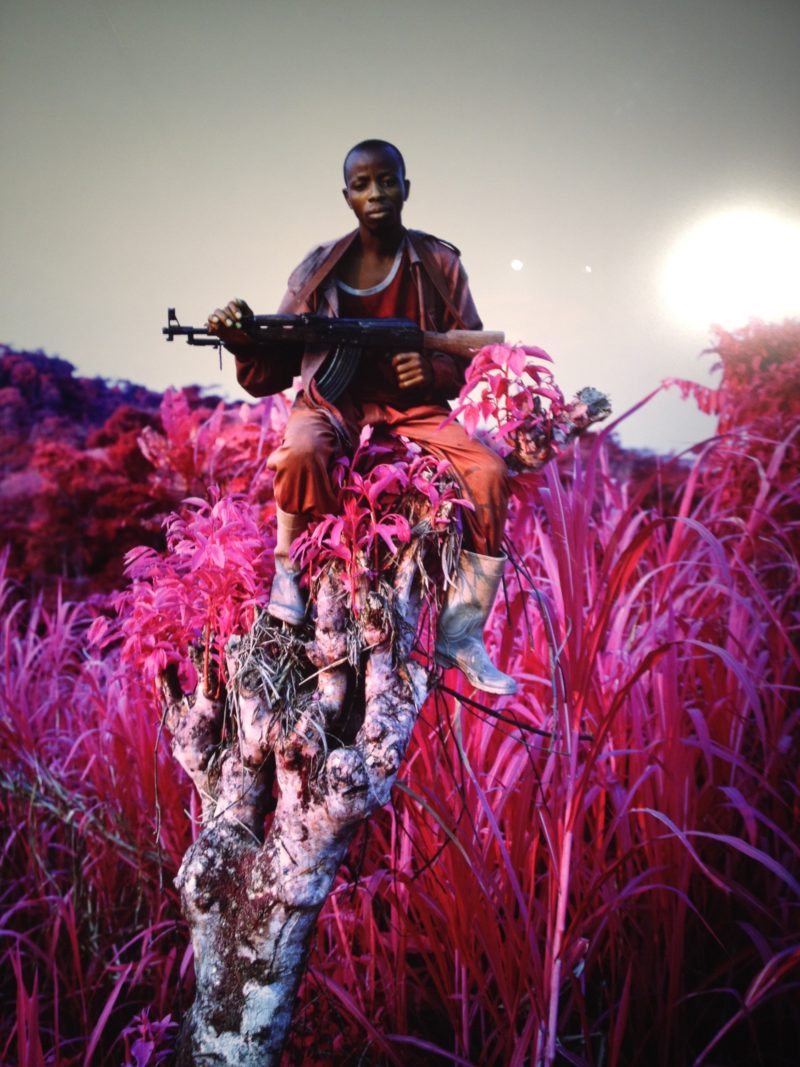

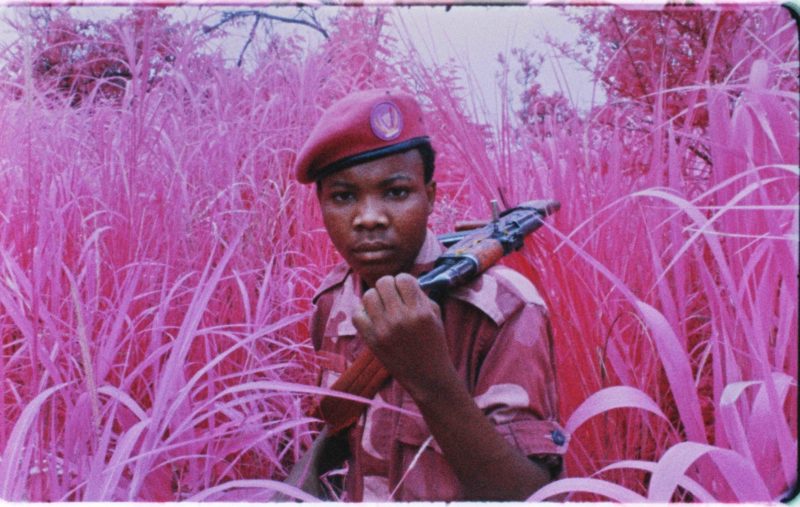

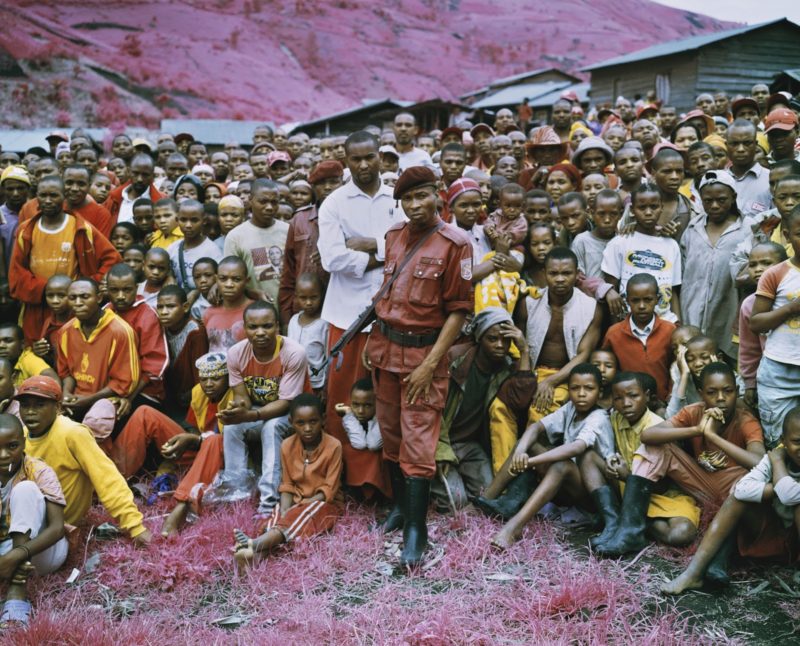

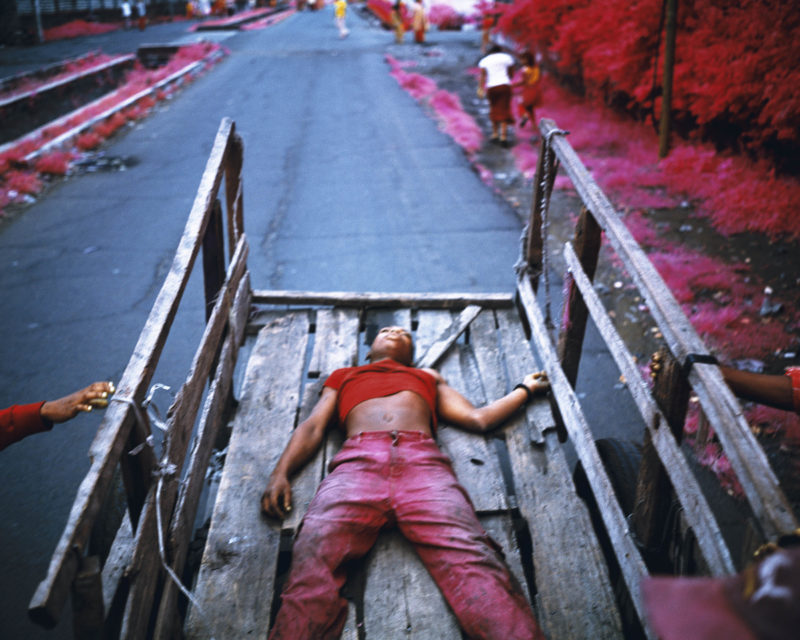

In his work across eastern Congo, Richard Mosse 1 focused on capturing the disturbing images of rebel groups fighting as they move from one place to another. The work displays the devastation brought about by the war, such as massacres, refugees, and systematic sexual violence.

The entire journey across the country took four years – from 2010 to 2014. The international press usually ignores the conflict in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, making Mosse’s work even more valuable and important.

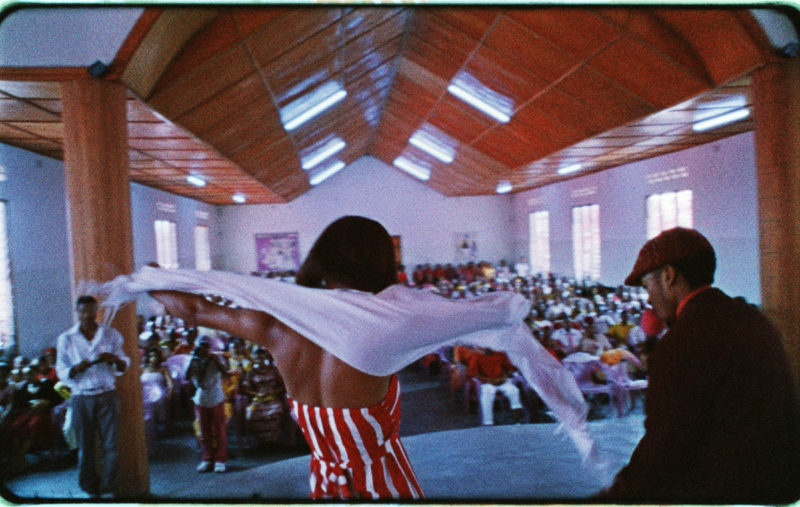

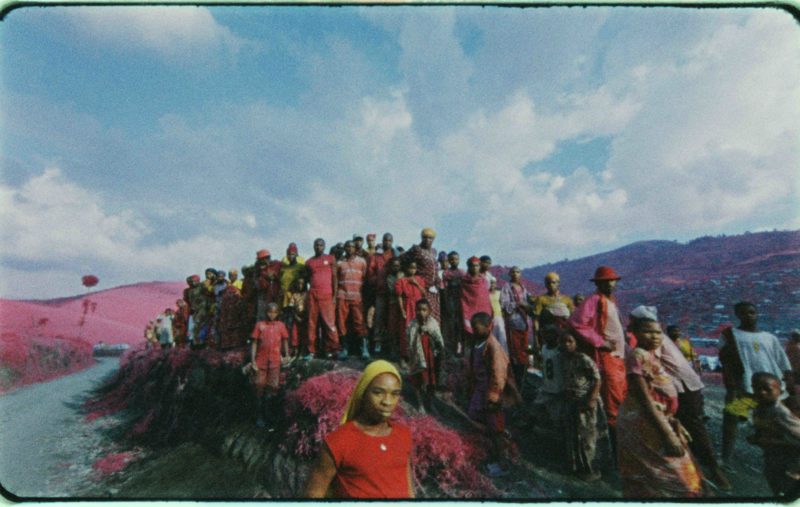

The commanding project The Enclave (2013) captures the eastern Congo – a land that is deceptively seductive and alluring from an outside eye. Mosse bases his photos on invisible edges of devastations and incommunicable horror. Enclave transcends art by also encompassing anthropology and journalism.

It was produced utilizing a recently superseded military 2 film technology designed in World War II to reveal camouflaged mechanisms concealed within the landscape. In his journeys across eastern Congo, Mosse collaborated with Trevor Tweeten – 16 mm cinematography, and Ben Frost – sound design.

The story of the Democratic Republic of Congo needed to be told by someone, but no one was willing to venture into the dangerous, war-torn jungle during the rainy season.

In one interview, Mosse said that he preferred working in such environments because the:

landscape turns into a sublime assault course – frail humanity versus overwhelming equatorial forces of nature. Think plane crashes, hemorrhagic fever, malaria, cars driving off cliffs.

The conflict in Congo

Congo’s conflict has, depending on your version of history, been going (on and off) for over 100 years, following the annexation of the Congo by Belgium’s King Leopold in 1908 34. The conflict has continued more consistently since 1997.

Like the mainstream media, the international political community has largely turned its back on the Congo. Recurrent massacres, human rights violations, and prevalent sexual violence 56 continue on, The Enclave attempts to bring to light this forgotten, to make this humanitarian disaster unforgotten and visible.

According to Richard Mosse, there are over 30 rebel groups in the region of eastern Congo. Most of them comprise young men that:

Many of them used to have an ideology, but they’ve long since forgotten it. They fall into alliances with each other, and then renounce them.

Why we don’t hear about this conflict

The works are rendered in vivid tones of lavender, crimson and pink. Mosse utilized this film to document the ongoing conflict in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo 78, in which 5.4 million people have died since 1998 and is fundamentally ignored by the mass media 910.

The reason why the news never reaches mainstream society is partly topographical. Congo receives four rainy seasons each year, making the jungle voracious. The groups of people are in constant movement, making it hard for the news of massacres and rape to get out of the jungle in time.

By the time photographers arrive, there is nothing left to see. It was this lack of trace that interested me, and ultimately the failure of documentary photography. Conflict is complicated and unresolvable, and it’s not always easy to find the concrete subject, the issue and put it in front of the lens.

A little about Richard Mosse

Richard Mosse is known throughout his conceptual documentary photography career for challenging society using photojournalism. This was laid bare in his work in the Democratic Republic of Congo – Enclave, which took the world by surprise in the same measure as the conflict it explores. Mosse gained worldwide recognition for these infrared images depicting the effects of war and refugee situations.

He is an Irish native, and was born in 1980 but lives in New York 11. He earned his masters of fine arts from Yale School of Art in 2008 and a postgraduate diploma, also in Fine Arts, from London 12-based Goldsmith in 2005. Mosse has worked in other countries faced with a humanitarian crisis such as Pakistan 13, Palestine 14, Iran 15, Iraq 16, Haiti, and former Yugoslavia.

Kodak Aerochrome

For Enclave, Richard Mosse employed a large-format camera alongside the infamous Kodak Aerochrome film, which is now discontinued. Kodak Aerochrome infrared film was developed in the 1940s by the U.S. military to identify camouflaged figures.

The film was hard to use, even for the military. Coupling that with the fact that DR. Congo is a sizeable impassable country, it is no telling how hard it was for Mosse to create the Enclave images. However, what helped him was that he started practicing using the Aerochrome film back in 2009. The film registers infrared light usually invisible to the human eye and turns the resulting landscape into vivid shades of lavender, hot pink, and crimson.

Richard Mosse was inspired to try the Aerochrome film when the manufacturer announced it was discontinuing its production:

It’s a very eccentric medium. I thought it might put me in an uncomfortable place where I didn’t know what I was doing, and that is a good place to be as an artist. Originally it had been used to reveal enemy camouflage, so I asked myself, where is an unseen narrative? Where is the most unlikely place you would use this film?

– Richard Mosse in The Telegraph, 1 Apr 2014 1718

Mosse published a book in 2011, which received considerate approval from readers and the world in general. The thought of producing a movie based on Enclave appeared again to him shortly after publishing the book. But the journey took him back to eastern Congo again with Trevor Tweeten – the filmmaker. The quest to process a film appeared to be a pipe dream when they only had 35 reels of film, which lasted about 11 minutes each and an old Arriflex SR2 movie camera.

Unusual colors

Traditionally, the palette of war photography has been portrayed as brown, green, black, and red. But in Enclave, Richard Mosse uses camouflage, dirt, guns, and blood. He shone new light on the way conflict is covered. Explaining why he uses these new approaches, Richard Mosse states:

I go to great lengths to keep my work as open as possible in terms of significance, trying especially hard to avoid didacticism. So the viewer can bring whatever they like to the work and its unusual colors. I suppose for me, though, the colors are deeply emotional, as I have developed a strong affinity for eastern Congo over my many journeys in the region.

So, for me, it’s a deeply personal response rather than a deliberately didactic provocation. If people are moved by the work to take a longer look at the humanitarian disaster in eastern Congo, that is superb.

Mosse’s installation

Mosse’s work comprises six double-sided screens installed in a large darkened room, thus producing a corporeally immersive experience. This disorienting and variegated art project is supposed to visually parallel eastern Congo’s complex conflict, bewildering expectations by compelling the audience to interact with the imagery from a collection of divergent viewpoints. Collaborator and sound designer Ben Frost composed audio that plays in the background through the six channels.

Video interview: Richard Mosse & The Impossible Image

Journeys in the Congo

During his journeys in the Congo, Mosse would stay in Catholic missions and interact with as many people as possible. And the more he interacted with people, the more he met more rebels, and the more complex his understanding of the situation became.

Mosse could travel long distances to encounter rebels. He said:

You’d take a Land Cruiser as far as you could go, about half a day depending on rain, and then you’d walk, stay a night, and then walk another day until you passed the front line and into the enclave. Once you’re in there, time changes, as does logic. Some of these rebels believe they are bulletproof.

Most of the time, Mosse would spend time alone to “appreciate the retreat into your imagination that happens. I love the black canvas,” and “spending time watching lizards creeping up on clouds of mosquitoes.”

Return to UK & Challenges

When he returned to the U.K. from Congo, he started to look for means to convert the images into a film, but he was short of cash. Mosse said:

I almost didn’t process the film, I was so horrified by my impending bankruptcy. I was looking for jobs as a dishwasher.

But upon looking at the image of the landscape shot he had taken.

I almost ignored it because it was a pretty picture, then I realized what had been staring at me in the face the whole time. The pink pushed the viewer into this extraordinary space, way past the threshold of the imagination and into science fiction, something pulsating, nauseous. We don’t see in pink, but we don’t see it black and white either. Whichever way you look at it, documentary photography is a constructed way of seeing the world.

Another problem was to find someone willing to process the film.

I went from lab to lab thinking. I am ruined. I can’t do anything with this amazing footage. But at last, I found an old-timer in Denver. It took him six months but finally, he cracked it.

A final trip to Congo & Near-death experience

The artist took a trip back to Congo for cathartic reasons. Speaking about his ordeal when he went back to Congo, Richard Mosse said:

I went to get closure, to say goodbye. I’d hired a car, and the driver was so arrogant, he drove off a bridge. It flipped, fell about 25 feet. We all survived, but I had to perform first aid in the middle of a cloud of mosquitoes, in the middle of a swamp, in the middle of the night, in the middle of nowhere with all my cameras everywhere, and I thought this is it, I’m finished. I’m finished with Congo.

Analysis

When one views the images, one will be mesmerized by the beauty and seductiveness of the region’s landscape. However, when reality finally sinks in, the colors suddenly become less fantastic and more grotesque and terrifying. The image of an innocent boy suddenly brings into sharp focus the rifle he is carrying. The appealing trees in the background throw into sharper relief the ragged tents, skeletons, and tombstones.

The world created by the images is without rules, and metaphorically, not even the rules of color. Enclave forces the reality to the face of the society in a more profound manner than the mainstream coverage of war many are used to. Richard Mosse uses the simple act of modifying the palate of the landscapes to alter society’s perceptions of war and chaos. He uses provocation to evoke strong reactions to situations that the masses are accustomed to by spreading into our day-to-day lives.

Conclusion

The imagery is both psychedelic and disturbing. Mosse’s view makes the forgotten unforgettable. The devastation that is currently invisible to mainstream society will never be unseen. It is essential that the international community not forgets nor ignores what has happened and continues to happen in the area.

Families are torn apart, prominence of violence and death stemming from the conflict, neighbors turning into enemies- this should never be forgotten. Those who visit Mosse’s installation will likely never forget the conflict that the images portray.

At the heart of the project is the artist’s exploration of the paradoxes and the perimeters of the abilities of art “to represent narratives so painful that they beyond language – and photography’s capacity to document specific tragedies and communicate them to the world.” Mosse stated. The role played by Enclave in bringing to light the atrocities shunned by society cannot be downplayed.

But we don’t hear about it, because they’re dying from lack of sovereignty and constant displacement, shitty diseases.

Photos

Landscapes

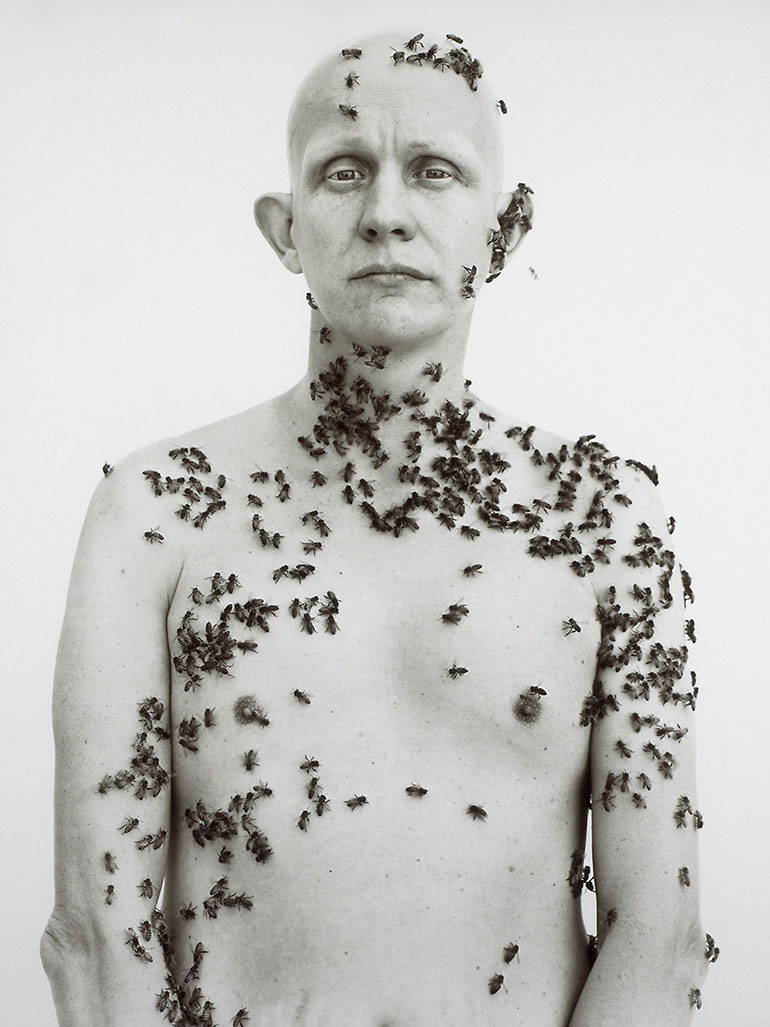

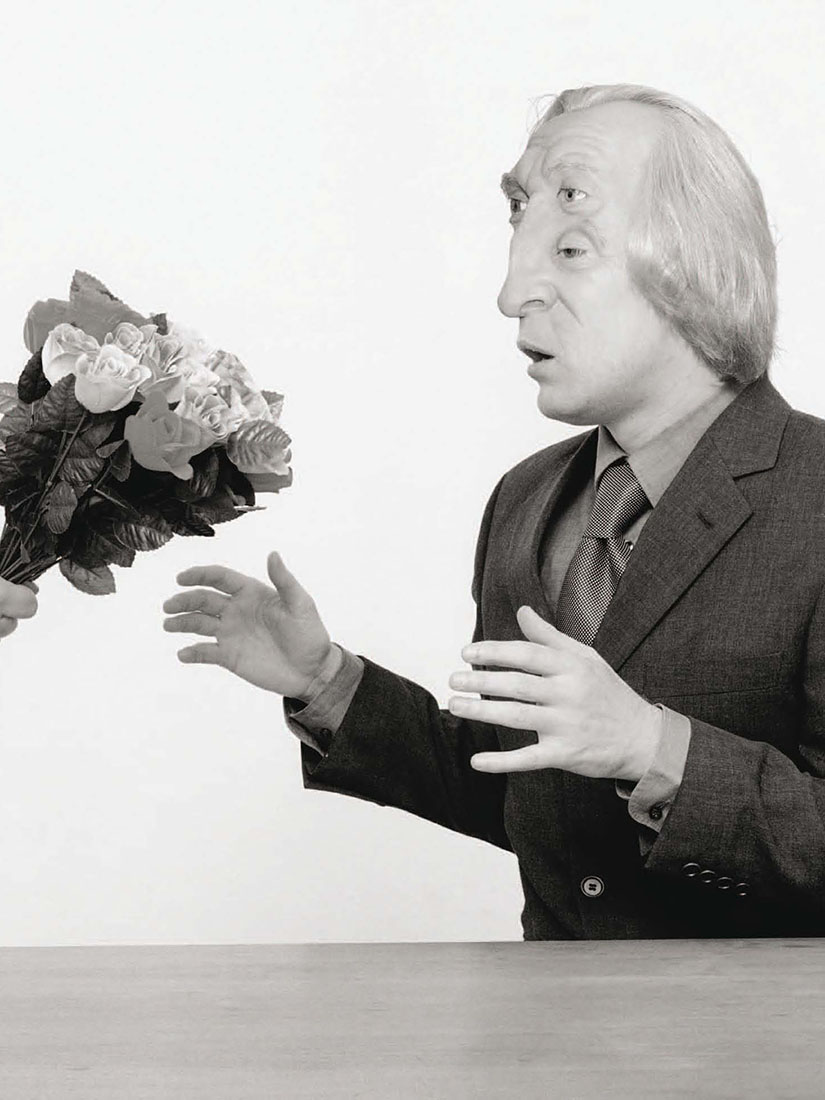

Portraits

Groups

Others

Venice Biennale, 2013

In 2013, Mosses participated in the Venice Biennale as an Ireland representative. He exhibited Enclave, explaining that the work aims to bring “two counter-worlds into collision: art’s potential to represent narratives so painful they exist beyond language, and photography’s capacity to document specific tragedies and communicate them to the world.”

Other exhibitions

Mosse has showcased his works at the Palazzi, Florence, the Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, the Bass Museum of Art, Miami, the Kunstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, the Center Cultural Irlandais, Pari, and many more. Enclave is part of collections such as the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art and the Martin Margulies Collection.

Film stills