Bio

Tsang Tsou Choi 1 was born on November 12, 1921, in Gaoyao, Guangdong, Republic of China 2, and died in Hong Kong 3 on 15, July 2007. When he was 16 years old, Choi traveled to Hong Kong. He worked manual jobs there, which was the only kind he was qualified to do as he was barely literate.

Tsou Choi was widely known in the West as the King of Kowloon. He never had a studio like many contemporary artists, but he started marking the streets of Hong with his distinct graffiti when he was 35 years old. Choi was arrested several times for what police perceived as vandalism 4.

His family disowned Choi because he was mentally unbalanced as well as a public nuisance. While his wife grew tired of his niggling obsessions that she also left him.

Locations of the paintings

After painting, the local authority would paint over his graffiti, but Choi would return later and reapply his messages immediately after the paint has dried. At the peak of his graffiti career, Choi grew an obsession with marking territories, which made his paintings ever-present in all areas of Hong Kong’s streets.

The locations ranged from utility boxes, lampposts, pavements, pillars, building walls, and street furniture 5 to abandoned cars 6.

He targeted his calligraphic in areas with high pedestrian traffic, where it would be noticed. His most common locations were Central and Tsim Sha Tsui. However, Choi was cautious not to place his graffiti in too prominent positions where they are likely to get painted over immediately.

Choi focused mainly on the occupation of the margins and oblique engagement. For example, he would place his inscriptions over a post box. The insignia of imperial power or mark walls near the gates of the Central Government Offices attracted him.

He also once painted on a park bench at Victoria Park in Causeway Bay because of its royal name. This way, he was metaphorically overwriting on the pre-existing inscription on the bench or the nearby statue of Queen Victoria to whom the park was dedicated to. The statue itself had been targeted with red paint and a mallet by artist Pun Sing Lui from the Mainland.

What did he write & Challenging authorities

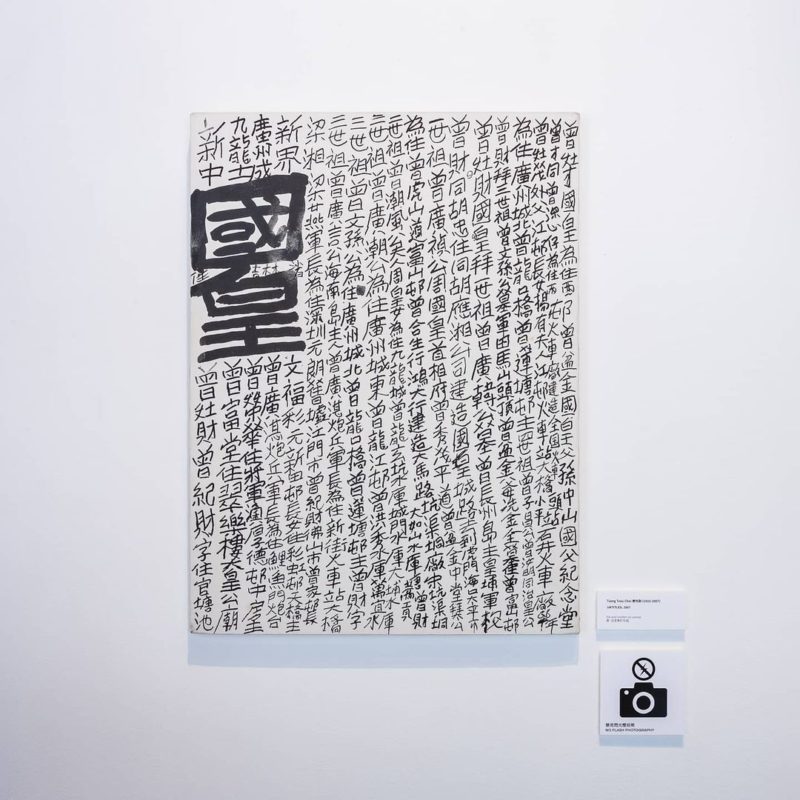

Choi’s calligraphic graffiti writings were unique in that they included his name alongside his title, which was Emperor or King of Kowloon, Hong Kong, or China. His family tree included a variable list of about 20 persons, some of them were famous emperors.

He often used the exclamation, “Down with the Queen of England!“. The artist often complained about the misappropriation of his land and demanded to be paid land taxes by the government.

Tsou Choi’s sense of the structure of power was never a static one, preferably, demonstrated awareness of the shifts that took place with that handover of power from British sovereignty. But even after the handover, he continued to attack the Chinese government.

Once, he painted on a flyover located directly opposite the Bank of China building. When it was first constructed, it was perceived in Hong Kong as a pre-handover forerunner of Chinese governmental authority.

Post-handover

Post-handover, his inscriptions invariably proclaimed that he was the rightful emperor of new China. This was shown by the inclusion of the two words ‘Guo Huang’ in his calligraphic and executed on a larger scale to drive the point home.

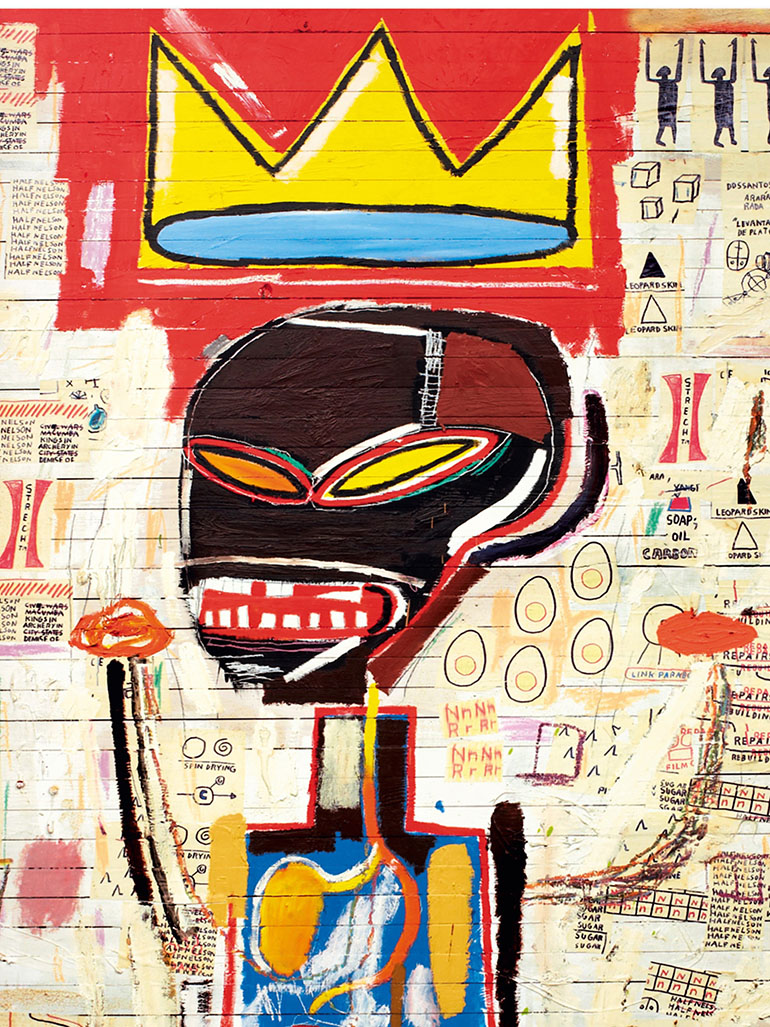

Choi’s imperial claim can be taken as a literal bid to oppose British royal authority. He believed the British crown had snatched family land in China. His calligraphic inscriptions also bore specifically Chinese connotations to authority: whether this is in the form of Mao’s calligraphic validation of a publication by writing its title on his hand or an imperial edict.

Exhibition

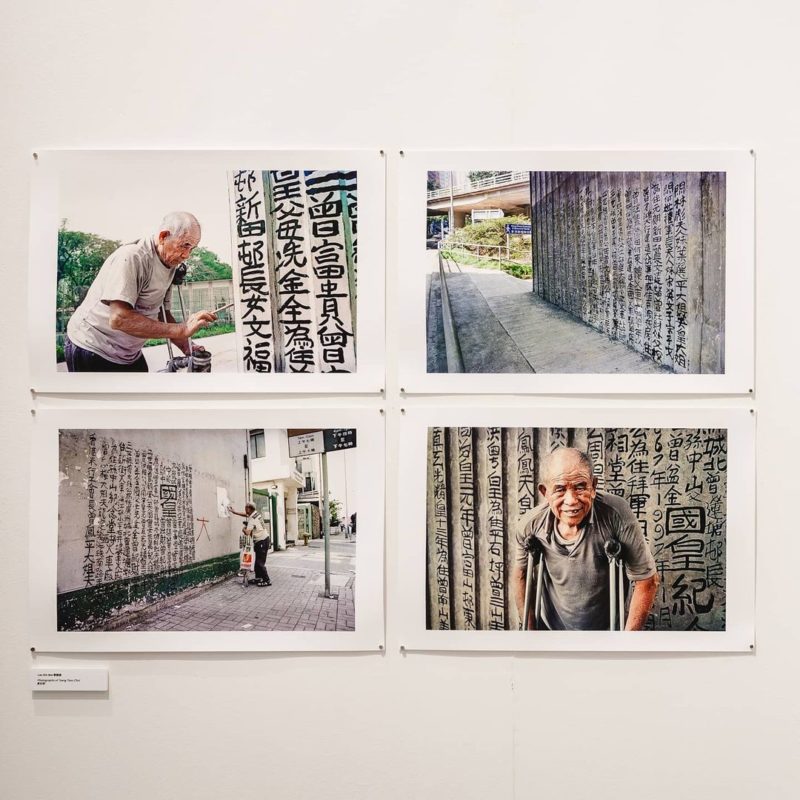

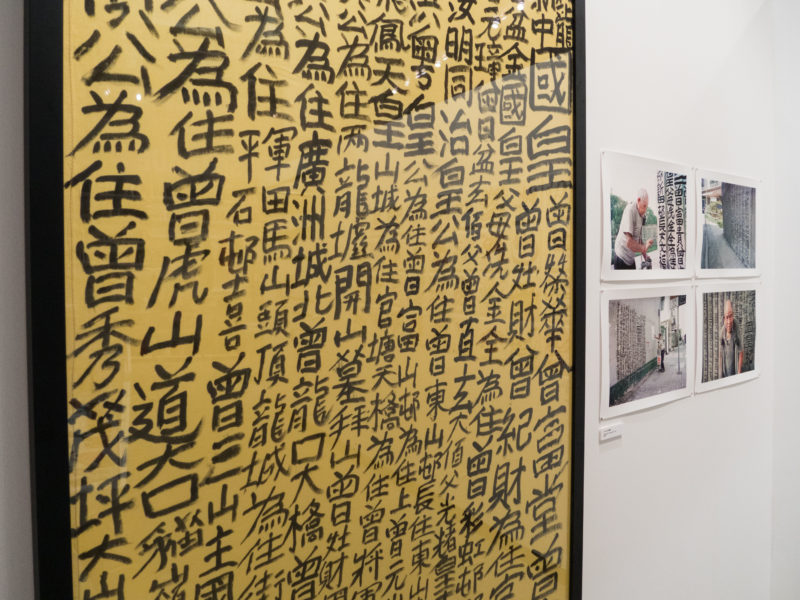

Before the handover, an exhibition was organized by Lau Kin Wau to showcase Choi’s work at the Goethe Institute Hong Kong – Hong Kong Arts Center, Wanchai. The show took place from April 24 to May 17, 1997, and was titled “The Street Calligraphy of ‘King of Kowloon’ Tsang Tsou Choi‘.

The exhibition featured a wide range of portable items that Lau had given Choi to write on. The artist also went on to fill the walls of the gallery with his inscriptions as well. The exhibition was a success, nevertheless. It succeeded in solving what many galleries had failed, which was to represent Choi’s artwork in a proper context.

Issues of exhibiting Choi’s work

However, the gallery also raised several issues due to transplanting the work of Choi from the street and pavements to an indoor art-related space. First, the choice of objects or sites on which the inscriptions were created was not one purely made by Choi.

The portability of the inscriptions meant that they could, in the future, be moved to other galleries or exhibitions which. The artist may not have willingly chosen or considered his level of competence, be aware of, and be showcased when he had not created them for.

Choi’s works derived their meaning from the associations of the topography and times of its placement. The loss of being site-specific 7 during the exhibition and the temporal belonging was a cause for concern. The inclusion of documentary photos of Choi’s street calligraphic works was the only way Lau could try to remedy the deficit.

While it was hard for Tsang Choi to find assistance from the art community, Lau is the only person who managed to develop a personal acquaintance with him. Lau provided the artist with a wide range of daily objects to paint on. This allowed Choi to retain a sense of writing on everyday objects as he was used to. However, this also created a feeling of conflict between the two different orders of reality.

In later years, Choi’s work was more or less sensitive to the subject of misrepresentation. Perhaps, this was partly because those involved couldn’t or didn’t involve the artist himself in the exhibition. Some of these exhibitions were being staged outside Hong Kong or after Choi’s passing.

Last years

During his last years, Tsang Choi lived in a retirement home and could no longer write on walls. His health was deteriorating slowly, but that did not stop him from creating more calligraphy. He continued his work on household linens, paper, as well as other mundane items.

Choi received international recognition for his writings. His works have been featured in such tours as “Power of the World“, which started at Grinnell College’s FaulconerGallery on October 6, 2000. His major commercial success came when the popular gallery Sotheby’s auctioned a board with his inscriptions for $7,050 in 2004 89.

Pop culture & Recognition

Many people never took him seriously. A Hong Kong magazine even named him as one of the city’s top ten least influential people. However, those who understood his work, or the underlying messages it carried, were impressed by him. In the art world, he influenced the works of artists such as Oscar Ho.

Beyond that, his work influenced numerous fashion designers, interior decorators, and art directors. Tsou Choi was featured in a commercial for Swipe cleaner. In it, he is seen cleaning away his permanent ink graffiti, declaring the product’s effectiveness to the consumers of Hong Kong.

Throughout his life, Choi’s calligraphic inscriptions were mostly viewed by the population negatively. Many thought it was vandalism of public property. In the mid-1990s, the artistic community was also unusual in taking a favorable interest in Choi’s work. Some found it challenging to formulate a way to present his works in exhibitions without misrepresenting the work or exploiting his artistic creativity.

After this exhibition, Choi’s work received widespread press coverage, propelling him into a new stratosphere than he was a couple of years before. He became known worldwide, and people outside Hong Kong started to pay attention to his work. His newfound fame was accompanied by controversy as many people in Hong Kong were unprepared to see him as anything beyond just a vandal.

A documentary was made about Choi at that time expressing the same consensus. But regardless, it provided an instance for a more comprehensive assessment of his work.

Analysis

Despite the public viewing him as insane, Tsang was artistically gifted. He managed to usurp the very language of power and authority.

Choi was dispossessed by his social pariah and lacked significant knowledge of an independent language of protest. But he made up for that by mimicking the language of authority itself, mentioning in his inscriptions to his family tree to strengthen his claim and emphasize a sense of belonging.

Whether you see Tsang Tsou Choi as an artist or a vandal, he had a message that he, even with his inadequate knowledge of the language, was successful in expressing.

More graffiti