149-179 E 8th St, New York, NY 10003, US Copy to clipboard

40.729896, -73.991017 Copy to clipboard

Before you go

Coffee & seating: The plaza features limited seating and two nearby cafés. Grab a coffee and enjoy people-watching while taking in the artwork.

Cube interaction: While the cube is designed to rotate, it may require significant effort to turn. Team up with others or use your legs for leverage if it feels stiff.

Historical note: The plaza has evolved significantly over 50 years, transforming from a small island into a larger space with vendors and public seating.

Nearby attractions: Explore the vibrant East Village, visit the Public Theater steps away, take a 16-minute walk to Walter De Maria's New York Earth Room, or a 15-minute walk to Alan Sonfist's Time Landscape.

Best visit time

Early morning or late evening provides a peaceful atmosphere with fewer crowds. Afternoons offer better lighting as the sun hits the sculpture directly.

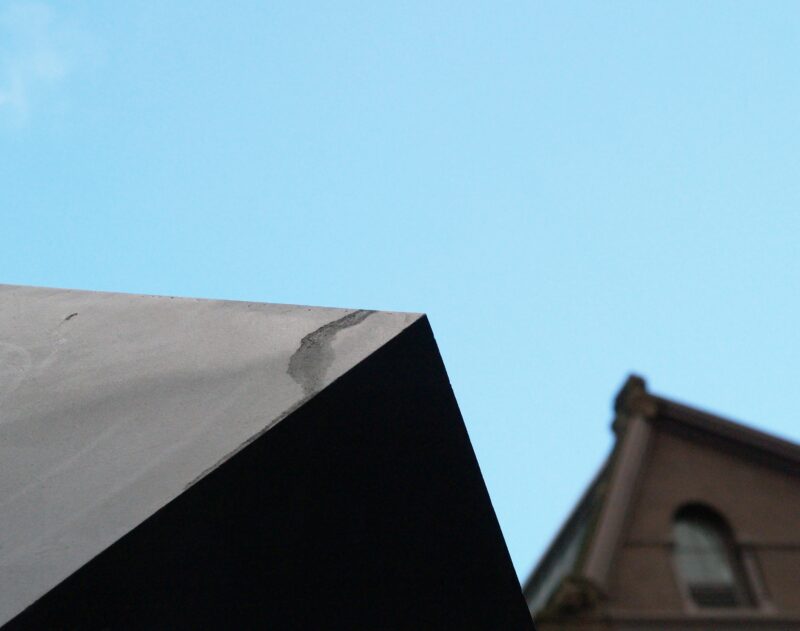

At night, The Alamo takes on a new character. While it is not illuminated with dedicated lighting, the glow from surrounding buildings and streetlights casts dramatic shadows on its surface, enhancing its geometric form.

Astor Place can be busy during peak hours, especially midday on weekends, with pedestrians, messenger bikes, and nearby students.

Directions

From Grand Central Terminal

By subway: Take the N, Q, R, or W train to 8 St-NYU. Walk 2 minutes.

By bus: Take M1, M8 buses to Astor Place.

From Times Square

By subway: Take the N, Q, R, or W train to 8 St-NYU. Walk 2 minutes.

By bus: Take M1, M8 buses to Astor Place.

Parking

Limited street parking is available in the East Village. Paid garages are located nearby.

Introduction

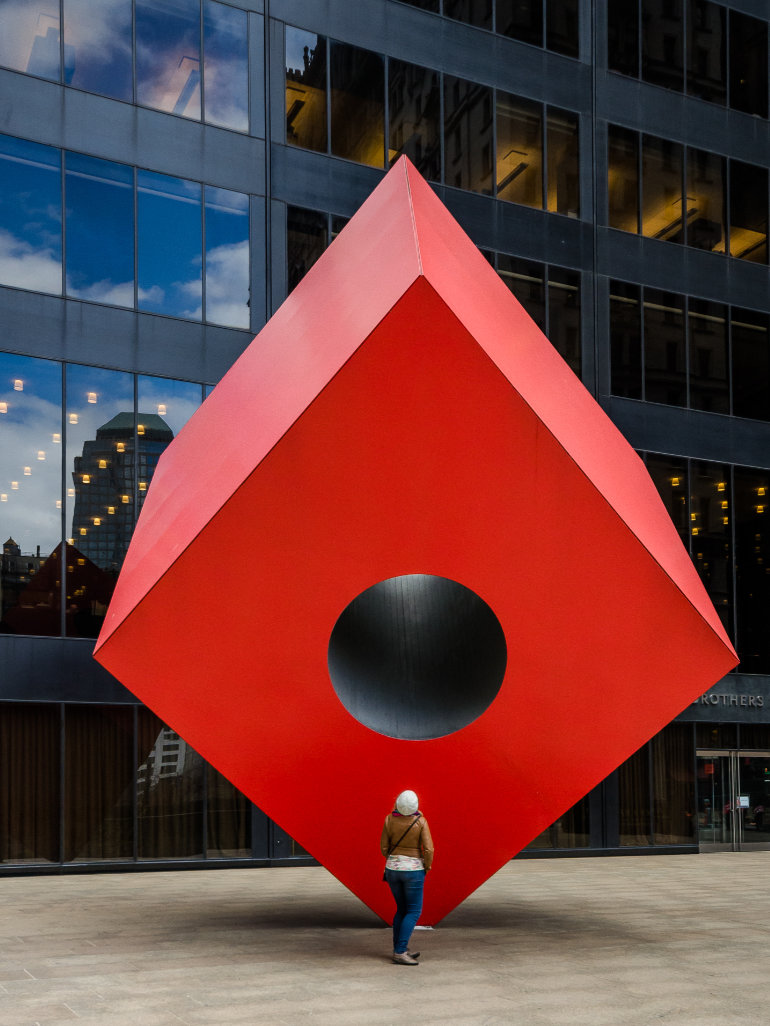

What is it about a simple geometric shape that can evoke strong emotions and ideas? In the heart of New York City’s 1 East Village, one such structure commands attention: The Alamo.

Crafted by renowned artist Tony Rosenthal 2 in 1967, this towering monument was designed from Cor-Ten steel 3, measuring 15 feet in height.

Originally created for a temporary public display in 1967, a petition by residents secured The Alamo’s permanent place at Astor Place. Often referred to as the Astor Place Cube, this masterpiece has solidified its place as one of Rosenthal’s most celebrated and cherished public artworks. Recognized as a symbol of both New York City and the broader world of public art, the sculpture holds a revered status as a landmark.

Rosenthal’s Alamo holds the distinction of being the first contemporary sculpture ever bought by New York City and the first permanent contemporary outdoor sculpture installed in the city 45. It was also the first time Rosenthal made a public art sculpture without being asked by an architect. The decision to purchase The Alamo was a landmark moment, showing how important the city thought contemporary art in public spaces was.

Creating the Alamo

The idea for Alamo came about when Donald Lippincott, who owned Lippincott Foundry, saw Rosenthal’s earlier work, especially Ahab, a 10-foot brass sculpture Rosenthal made by hand for the Whitney Museum’s Annual Exhibition in 1966. Lippincott liked what he saw and got in touch with Rosenthal. This connection led to the creation of Alamo and marked a significant moment in Rosenthal’s career as a sculptor.

Unlike many other metal sculptors who relied on fabricators for larger pieces, Rosenthal had always personally crafted all of his metal sculptures, even those as large as 20 or 30 feet. So, when Lippincott suggested the possibility of scaling up his sculptures beyond what he could manage in his studio, it was the perfect opportunity for Rosenthal to start incorporating fabricators in the process.

The Alamo marked a departure from Rosenthal’s earlier works, blending geometric abstraction with public interactivity to create a uniquely participatory experience.

In 1965, Rosenthal began making small five-inch cubes from balsa wood. He then transitioned to crafting larger cubes out of bronze, eventually reaching five-foot cubes. Though Rosenthal was skilled at hand-cutting and welding brass, it still took him four months to get the solid appearance he wanted. Fabrication, while giving up some control, proved faster. A 15-foot cube was made at Lippincott in just three months.

Ahead of its time

Created during a period of cultural transformation in the late 1960s, The Alamo redefined the possibilities of public art. Moving beyond static, commemorative sculptures, its participatory design broke barriers, reflecting societal calls for greater accessibility and interaction.

This pivotal shift served as a precursor to the growing trend of experiential art and positioned The Alamo as a work ahead of its time for several reasons:

Geometric abstraction

The sculpture’s design, composed of interlocking geometric shapes, was innovative and ahead of the dominant artistic trends of its time. In the 1960s, geometric abstraction was gaining popularity in the art world, but The Alamo stood out for its boldness and simplicity in form.

Interactive public art

Unlike traditional static monuments, The Alamo invited interaction 6. Its rotating segments let viewers physically engage with the sculpture, making it an ever-changing artistic experience. Its smooth, cold steel invites touch, while the sound of grinding metal when pushed adds a visceral sensory dimension, further deepening its connection with audiences.

Rosenthal transformed a minimalist cube into an interactive public monument, making abstract art accessible while maintaining its aesthetic sophistication. This interactive aspect helped to build the growing interest in participatory art while also blurring the boundaries between the artist and the audience.

This was quite unusual for the 1960s. During that era, most public sculptures were static monuments or statues meant to be admired from a distance.

Rosenthal did not originally design it to be interactive 78:

I actually thought we would put it on this post and we’d turn it to the position we wanted it and then stick it like that. I did not realize that the turning was such a factor in people’s enjoyment of it.

In a 1968 interview 910, Rosenthal reflected on the installation of The Alamo:

The fact that it moves allows people to participate. Even climbing on it shows engagement, whether they realize it or not. If it had been monumental in scale, it would have lost its human scale, which is important. I’m delighted—it’s a friendly object.

Urban integration

The Alamo was placed in a busy city area and designed to fit in with its surroundings. Its modern style matched well with the buildings around it, showing the city’s energy and embracing the idea of making urban spaces better.

In winter, snow contrasts sharply against the dark Cor-Ten steel, emphasizing its geometric form, while in summer, sunlight highlights its patina, creating a dynamic interaction with its surroundings.

Sculptures were commonly seen as standalone artworks rather than as integral elements of the cityscape. As such, in the 1960s, most sculptures were typically placed in parks, plazas, or other public spaces where they could be admired from a distance. These locations were often chosen for their aesthetic appeal and visibility rather than for their integration with the surrounding urban environment.

Symbolism & ambiguity

The title, The Alamo, references the site of the 1836 battle in San Antonio, Texas. Despite this historical nod, the sculpture’s abstract form invites diverse interpretations, deliberately avoiding any representational connection.

It’s abstract, which means people can see different things in it. This openness lets each person give their own meaning to the sculpture, unlike older art that usually showed things or people clearly.

Public reception & controversies

Public reception of The Alamo has been overwhelmingly positive, with the sculpture becoming a beloved New York City landmark. However, some controversies have arisen over the years, particularly regarding its maintenance.

Periods when the cube could no longer spin sparked criticism of the city’s handling of its upkeep. Additionally, debates arose about whether such artworks should remain in public spaces, with some arguing they lacked cultural relevance. Graffiti 11 and occasional vandalism 12 have also posed challenges to maintaining its iconic status.

Maintenance of The Alamo involves periodic restoration, addressing wear from public interaction, and ensuring the mechanism for its rotation functions smoothly. In 2023, restoration costs were covered by the Rosenthal estate, demonstrating the ongoing investment required to preserve such public art landmarks.

While its cultural significance outweighs its economic value, The Alamo represents a significant investment in public art, reflecting New York City’s bold commitment to contemporary art during the 1960s.

2023 restoration

Apart from brief periods of absence for conservation and the addition of space for a pedestrian plaza in 2005, 2014-2016, Tony Rosenthal’s The Alamo has been a beloved spinning attraction for over five decades.

For at least a year, the mechanism that allowed the Cube to spin had not been functioning properly. In 2023, however, New York City Transportation Commissioner Ydanis Rodriguez and the Tony Rosenthal Art Estate announced an agreement to refurbish the Alamo sculpture. Versteeg Art Fabricators completed a full restoration of the sculpture, with the costs covered by the Rosenthal estate.

Versteeg Art Fabricators had previously restored the Cube in 2005. The last time the Cube was removed was in 2014 by DOT and DDC during the capital reconstruction of Astor Place. This reconstruction included the creation of a permanent car-free plaza space by DOT.

The sculpture was reinstalled in the plaza in 2016, at which point DOT formally took on maintenance responsibilities as part of the agency’s Permanent Art portfolio, which consists of 23 works in total. Following its recent restoration, The Alamo is once again open to the public, with an upgraded spinning mechanism expected to function for the next 20 years 1314.

Conclusion

Over its five decades of existence, The Alamo has witnessed significant changes in its surroundings. Originally placed in a small traffic island, it now occupies a car-free pedestrian plaza, reflecting broader urban trends toward walkable and community-oriented spaces. Its ability to adapt to these changes while maintaining its iconic status highlights its lasting relevance.

The Alamo remains a cherished part of the city’s artistic landscape. What sets it apart is its ability to be both monumental and playful: A serious minimalist sculpture that invites joy and interaction without taking itself too seriously.

As Kendal Henry, assistant commissioner of public art at the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, noted 1516:

This … is one of the most successful works of art in New York City.

As it continues to spin, The Alamo reminds us of art’s power to reshape our interactions with the urban landscape. How many public spaces today could benefit from such dynamic creativity?

Explore nearby

Astor Place Plaza

Barry McGee's tag muralsInstallation ended (removed in 2010)1 km away

Barry McGee's tag muralsInstallation ended (removed in 2010)1 km away

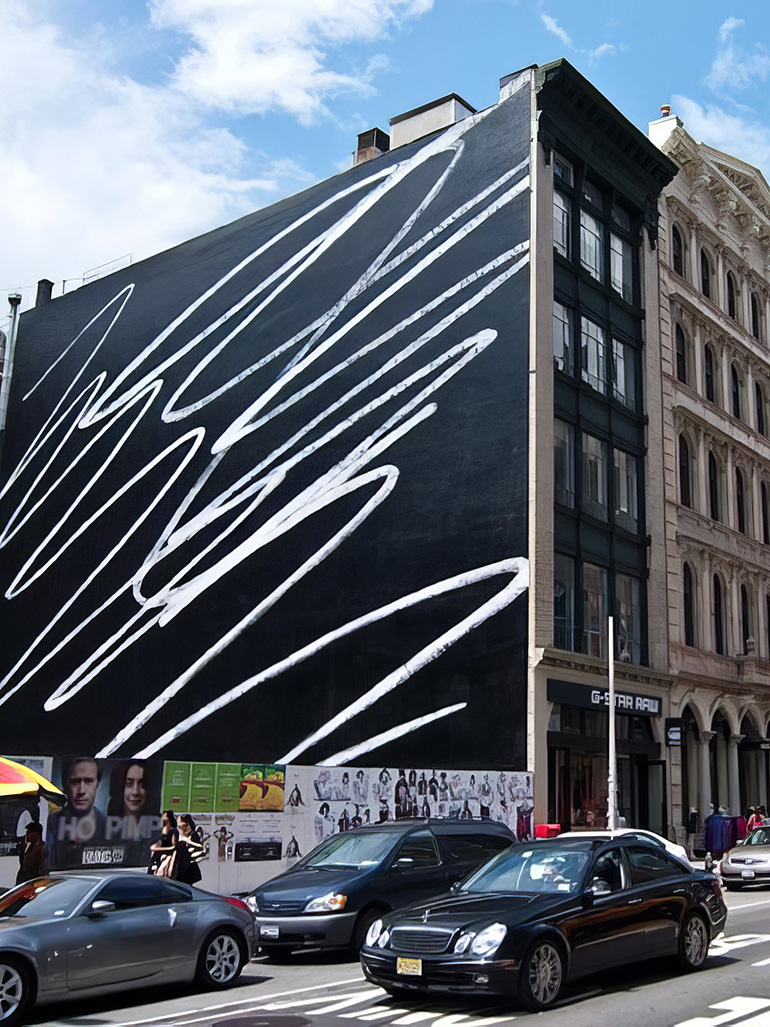

Karl Haendel's scribble muralsInstallation ended (dismantled in 2009)1 km away

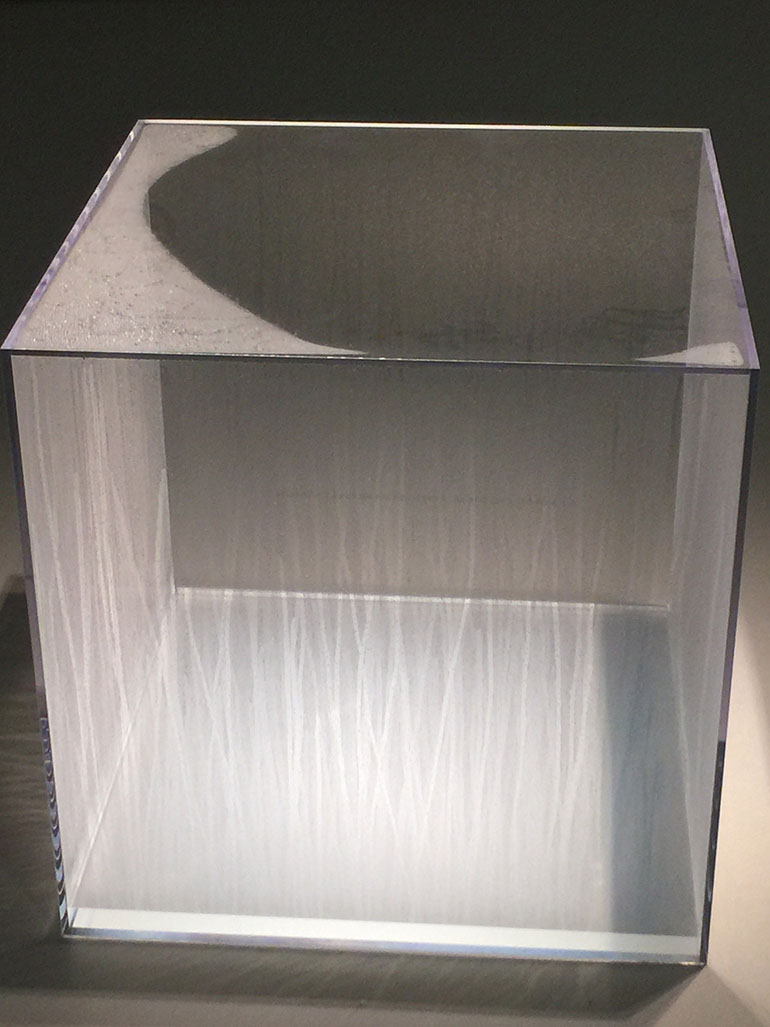

Karl Haendel's scribble muralsInstallation ended (dismantled in 2009)1 km away Snarkitecture's SwayExhibition ended (dismantled in 2019)2 km away

Snarkitecture's SwayExhibition ended (dismantled in 2019)2 km away Joseph Beuys' 7000 Oaks2 km away

Joseph Beuys' 7000 Oaks2 km away