Introduction

As an alumnus of the Central Academy of Fine Arts 1 in Beijing 2, Zhang Huan 3 is one of China’s 4 most influential artists. His work revolves around exploring both national and personal identity through performances.

Initially, his work was entirely expressed in the form of performance. Later, he incorporated photography to counter the ephemeral nature of performance art so that he could document and archive his temporary work.

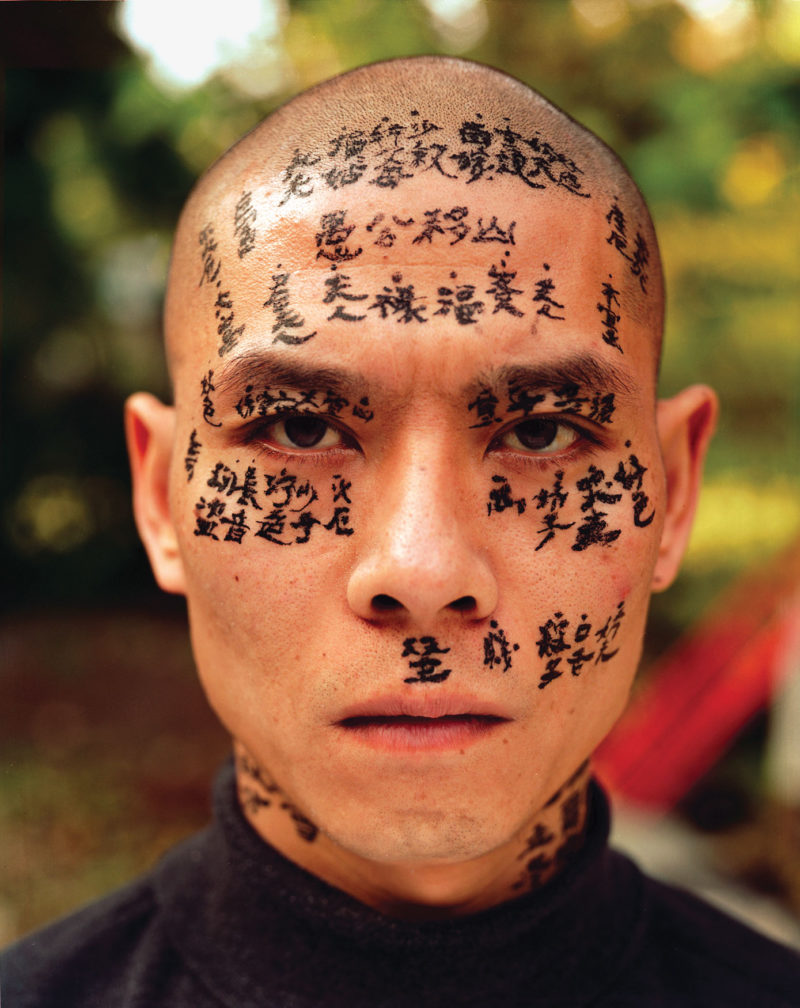

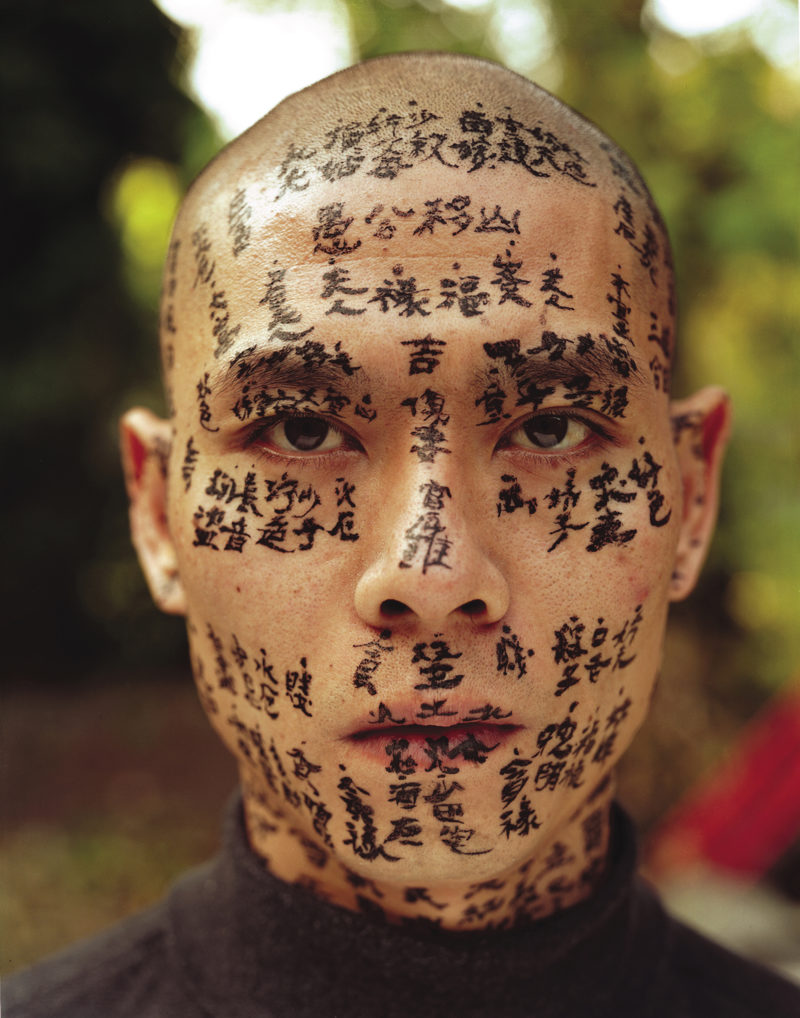

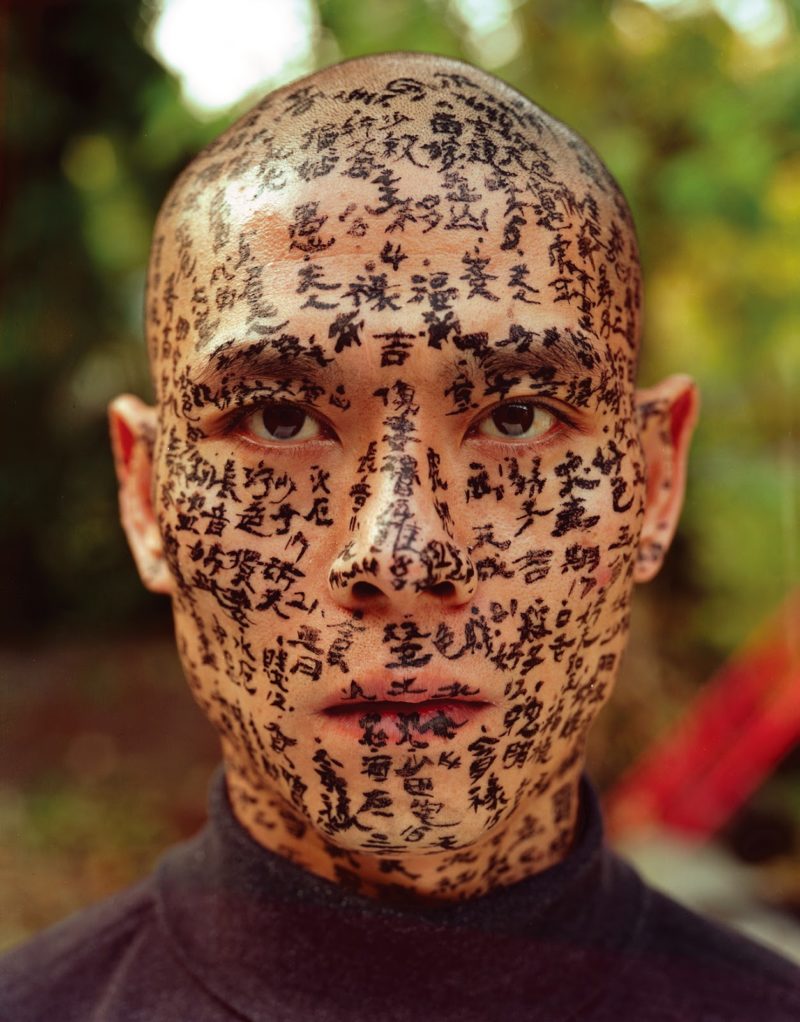

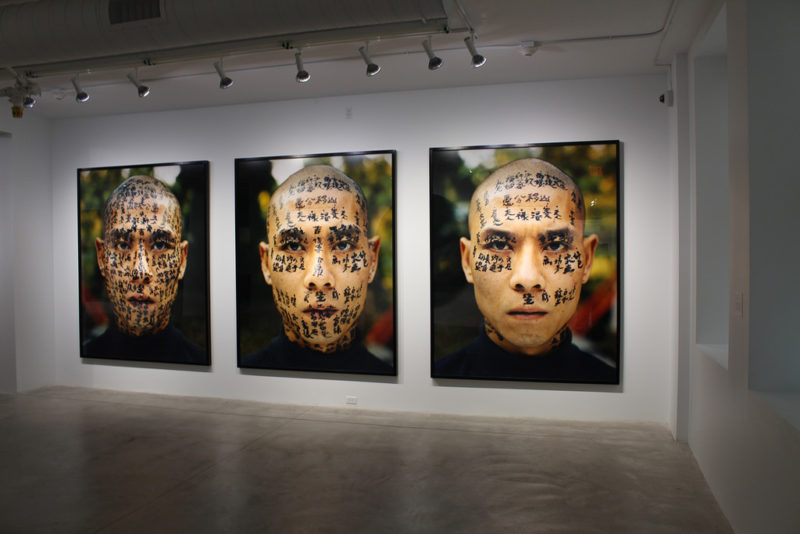

Family Tree

Zhang Huan began using his face in late 1998 with his well-known Foam series before taking it to the next level with Family Tree.

He moved to New York in the late 1990s, a move that he says affected the way he made art as well as his sense of identity. With Family Tree, which was created as soon as Huan moved to the United States, the artist offers his face as a medium on which names, stories, and words connected to his cultural heritage and written. In an interview, Zhang said 56:

The experience overseas put me to thoroughly understand the circumstances for Chinese people to live in a foreign country. […] I gained more experience in my travel… I got to realize more clearly the direction of art which I pursued heartily.

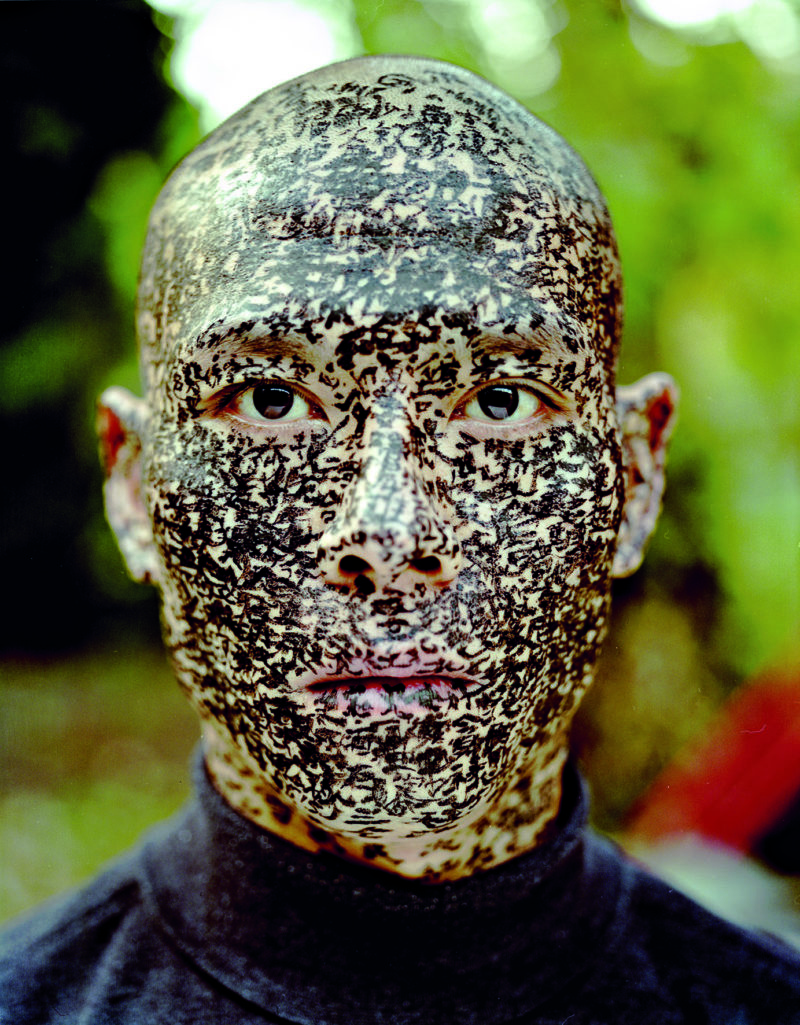

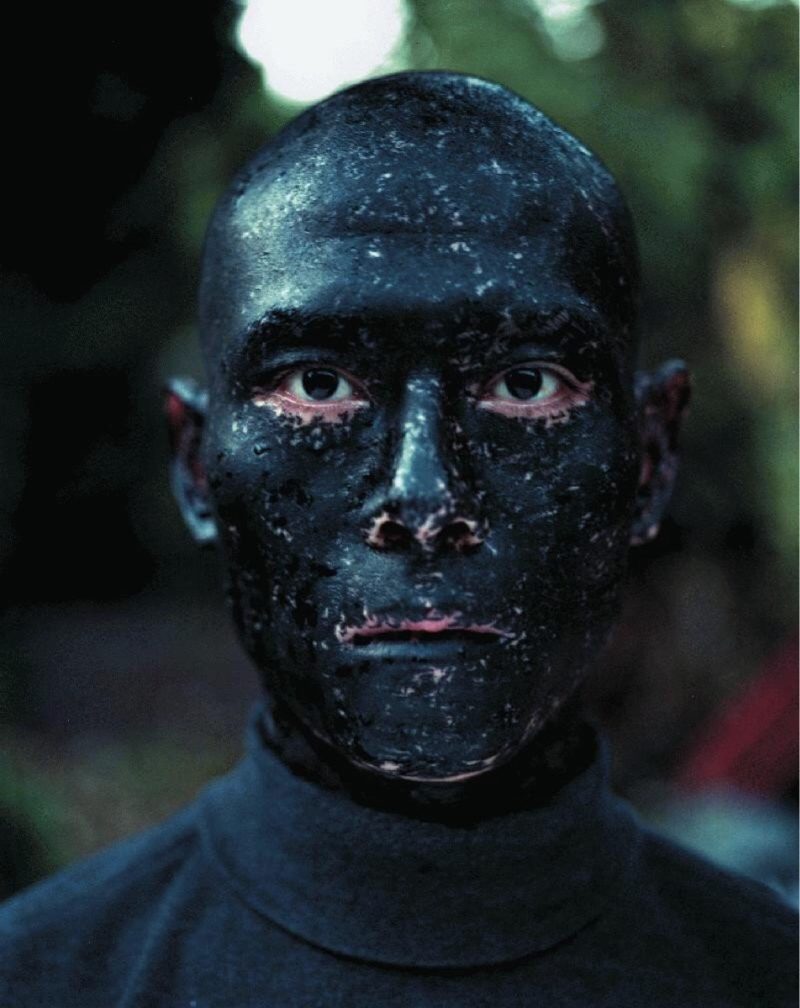

The piece consists of nine photographs taken gradually as Zhang’s face became obscured with words until it was covered entirely in inked calligraphers 7.

How the work was created

Three calligraphers worked with the artist to engrave the words. They wrote a combination of names known to Zhang, personal stories, learned tales and random thoughts on his face.

The calligraphers also used words from the old Chinese practice of physiognomy. This ancient practice involves mapping personality characters and divines the future based on an individual’s facial features.

As the calligraphers inscribe the words on Zhang’s face, he uses a camera to record the entire evolution of this short-lived performance. This way, he probed the correlation and arbitrariness between his natural and constructed self.

In the end, both calligraphy and physiognomy cancel each other. When the two practices are applied to Zhang’s face as a visual lexicon, the artist loses all his identifiable markers.

The story behind it

Family Tree was created after Zhang experienced an identity crisis after relocating to New York. He said 89:

I often find myself in conflict among the environment I live in. And feel surrounded by an intolerable self-existence. Therefore, when these problems occur within my body, I find that my body is the only direct approach that allows me to feel the world and also let the world know me.

After moving to New York, Zhang was unsure who he was as an artist and a person.

Family Tree was supposed to represent the artist’s lineage. The blacking out of his face serves as an allegory of how his culture might completely subsume his identity.

More culture is slowly smothering us and turning our faces black. It is impossible to take away your inborn blood and personality. From a shadow in the morning, then suddenly into the dark night, the first cry of life to a white-haired man, standing lonely in front of a window, a last peek of the world and remembrance of an illusory life. […] My face followed the daylight till it slowly darkened. I cannot tell who I am. My identity has disappeared. This work speaks about a family story, a spirit of family.

In the middle of my forehead, the text means ‘Move the Mountain by Fool (Yu Kong YI Shan)’. This traditional Chinese story is known by all common people, it is about determination and challenge. If you really want to do something, then it could really happen. Other texts are about human fate, like a kind of divination. Your eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheekbone, and moles indicate your future, wealth, sex, disease, etc. I always feel that some mysterious fate surrounds human life which you can do nothing about, you can do nothing to control it, it just happened.

Analysis

Zhang Huan tries to communicate with Family Tree that the density of traditions and culture obscure an individual. It only becomes clear again in the last photo where the artist seems vivacious and the legibility of the calligraphy has washed out.

Christopher Philips, who curated the Chinese photography exhibition Then and Now: Life and Dreams Revisited 1213 for the Walther Collection in 2018, said this about Family Tree:

As you see his face slowly disappearing beneath the blackness, you come to feel the elaborate web of social and cultural relations smothering any sense of the individual. But Zhang’s suborn, unchanging expression suggests resistance – a refusal to allow his identity to be consumed by the tide of tradition.

Inspiration

Family Tree is likely to have been inspired by a 1986 work by Qiu Zhijie 14 titled Writing the ‘Orchid Pavilion Preface’ One Thousand Times 1516.

In this piece, Qui also used ink and a brush. He inscribed an excerpt of improvisational texts describing an assembly of the intellectual commonly credited to Wang Xizhi (303-361 AD) and conserved in later generations as a calligraphic standard. In this work, Qui copied these texts over and over again until the small white sheet of paper was completely black.

Conclusion

With Family Tree, Zhang Huan explores his culture and selfhood. By covering his entire face with calligraphy, the artist duly identifies himself as being Chinese, without the particularity one would find he was living in his homeland, which would be marked by education, hometown, and family background. The work suggests that the artist recognizes his genealogy as Chinese.

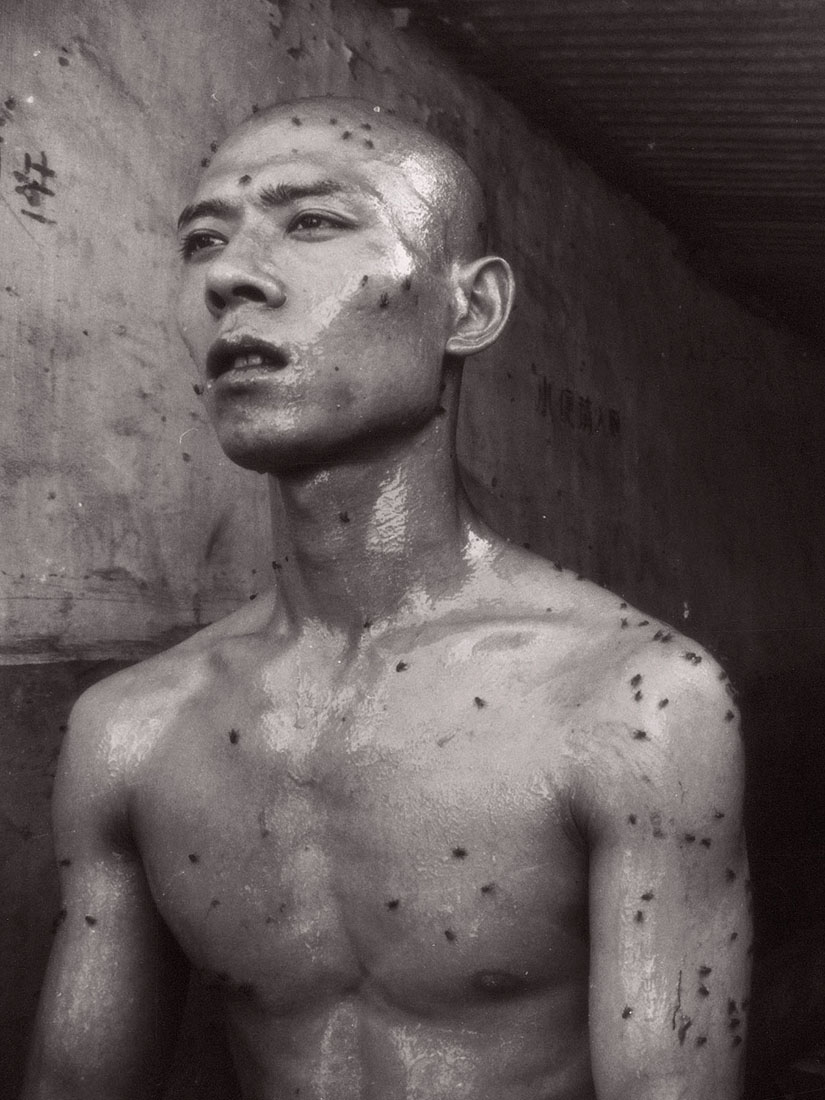

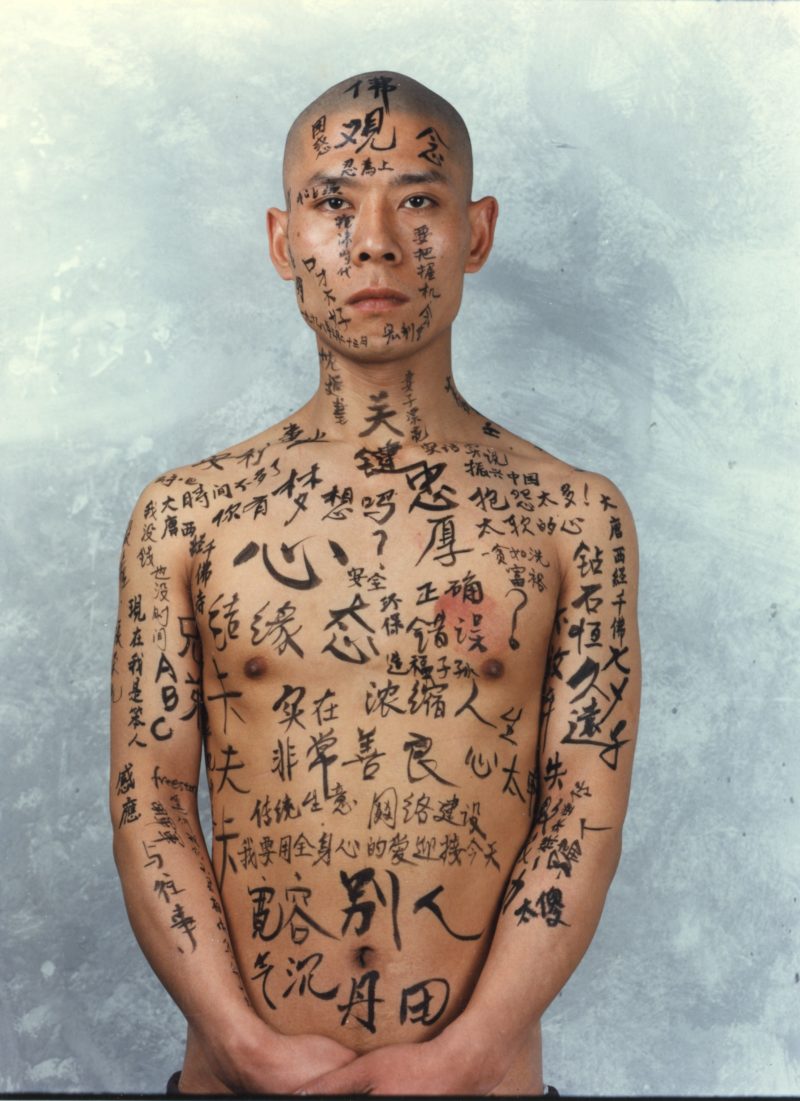

1/2, 1998

In another performance, Zhang has also covered his skin by others. Called 1/2 (Text) and created in 1998, this piece was made just before the artist moved to the US.

When the Chinese government closed the Beijing East Village, Zhang Huan moved to New York City. During this phase, he did review not only his artistic approach but also his life in general. Being away from his home country, he experienced feelings of estrangement as a foreigner.

In 1/2 (Text), he let friends cover his face and his upper body with words or phrases in black ink, resulting in the artist’s ethnicity being written on his skin.

The Chinese characters, unreadable for most Westerners, represent his body wandering around Western culture, showing that both Zhang, as well as his language, would be difficult to understand. This self-portrait symbolizes the challenging transcultural journey the artist was about to start.

Speaking about the performance, he said 1718:

The body is the only direct way through which I come to know society and society comes to know me. The body is the proof of identity. The body is language.

Shanghai Family Tree, 2001

In the same year Zhang created Family Tree, in 2001, he also made another version of the same piece titled Shanghai Family Tree, in which he posed with two other people – a man and woman – and had their faces inked with Chinese characters.

In this work, the artist appears to suggest the significance of language, which though it can overwhelm the individual, also defines the person’s association with society.

Family Tree, 2015

In 2015, Klaus Biesenbach, then Chief Curator at Large at The Museum of Modern Art 19, and Hans Ulrich Obrist, co-director of the Serpentine Gallery 20, curated the live-art exhibition 15 Rooms.

The show at the Long Museum West 21, Shanghai 22, lasted six weeks and included heavyweights such as Marina Abramović 23, Allora & Calzadilla 24, Cao Fei 25, Bruce Nauman 26, Yoko Ono 27, Xu Zhen 28 as well as Zhang Huan.

Zhang displayed a new version of Family Tree, painting genealogy on faces.

About Zhang Huan

Zhang Huan graduated in 1993 from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing with an advanced degree in traditional painting techniques. Most of his artworks contain powerful messages and sometimes disturbing self-portraits.

Especially in his earlier works, he often recorded his body in extreme states, including bound and suspended by chains, covered in a suit made from meat 2930, locked up in a disgusting toilet 3132, lying on a bed of ice, and subjected to flying sparks.

He has had numerous gallery and museum exhibitions, including at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center and at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art 33.

The layers of ideas the artist explored in his early performance art, conceived of as existential explorations and social commentaries, have carried through to the more traditional studio practice he embraced upon moving to Shanghai in 2005, after living and working for eight years in New York City.