Introduction

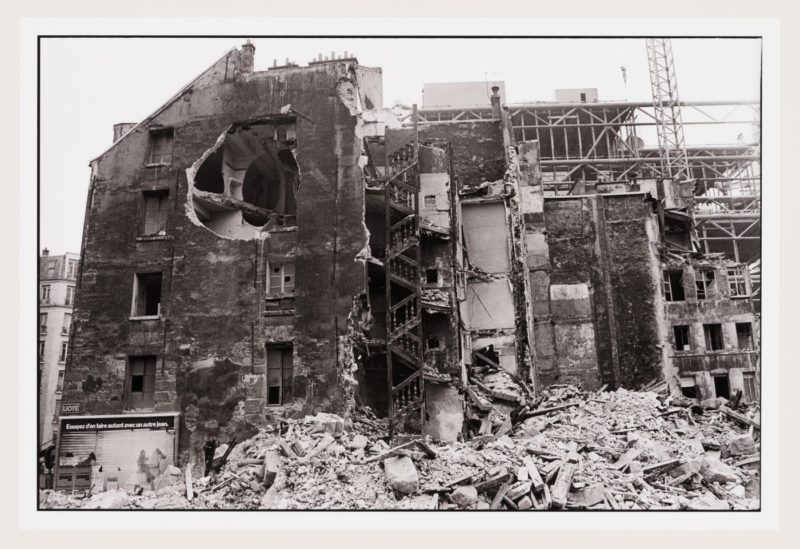

For the 1975 Paris Biennale, Gordon Matta-Clark 1 made big cone-shaped holes in two buildings near the Centre Georges Pompidou. The action took place in Les Halles, a neighborhood that was being demolished. Matta-Clark aimed to permit passers-by to peek through to the Centre Pompidou while it had been under construction.

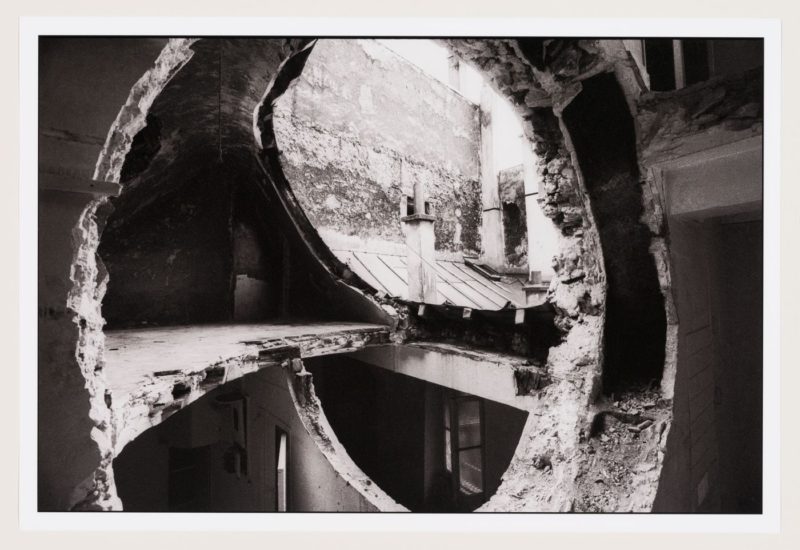

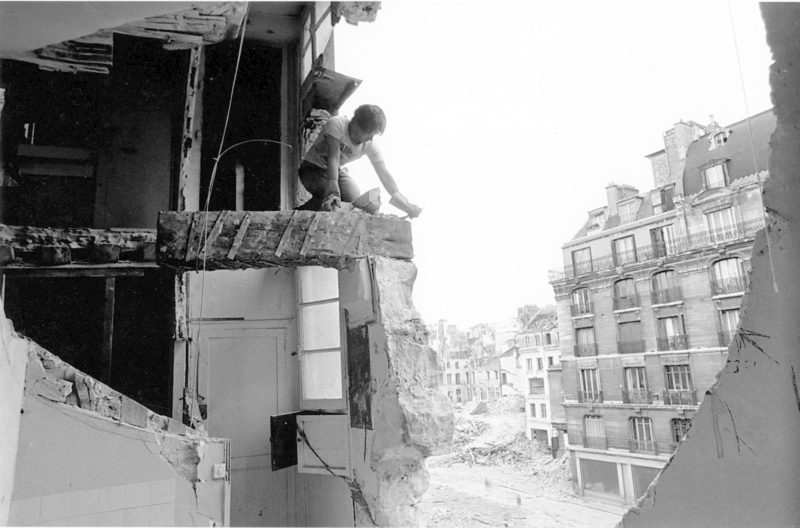

Conical Intersect (1975) was a torqued, spiraling ‘cut’ into two derelict seventeenth-century Paris buildings adjacent to the development site of the Centre Pompidou. With this site-specific work 2, Matta-Clark opened these old residences to light and air and commenced a dialogue about the character of urban development and the public role of art.

Who was Gordon Matta-Clark?

Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978) was one of the sons of the famous Chilean surrealist 3 Roberto Echaurren Matta. After studying architecture in New York, he quickly gained his place in the margin of the prevalent architecture. In the 1970s, he was very active in the New York avant-garde scene. However, he preferred to explore the limits of architecture and art rather than being an architect or artist.

He criticized the conventions within architecture and the visual arts through his work, and he also demanded attention for problems concerning social and urban development. The interventions 4 in the 1960s and 1970s emphasized the condition of NYC as a land of demolition. Gordon Matta-Clark didn’t destroy anything himself, but, as he put it, experiment with the alternative uses of those places that we are most familiar with. He called his work performances. Matta-Clark saw the making of incisions and the transforming of buildings as a part of this work.

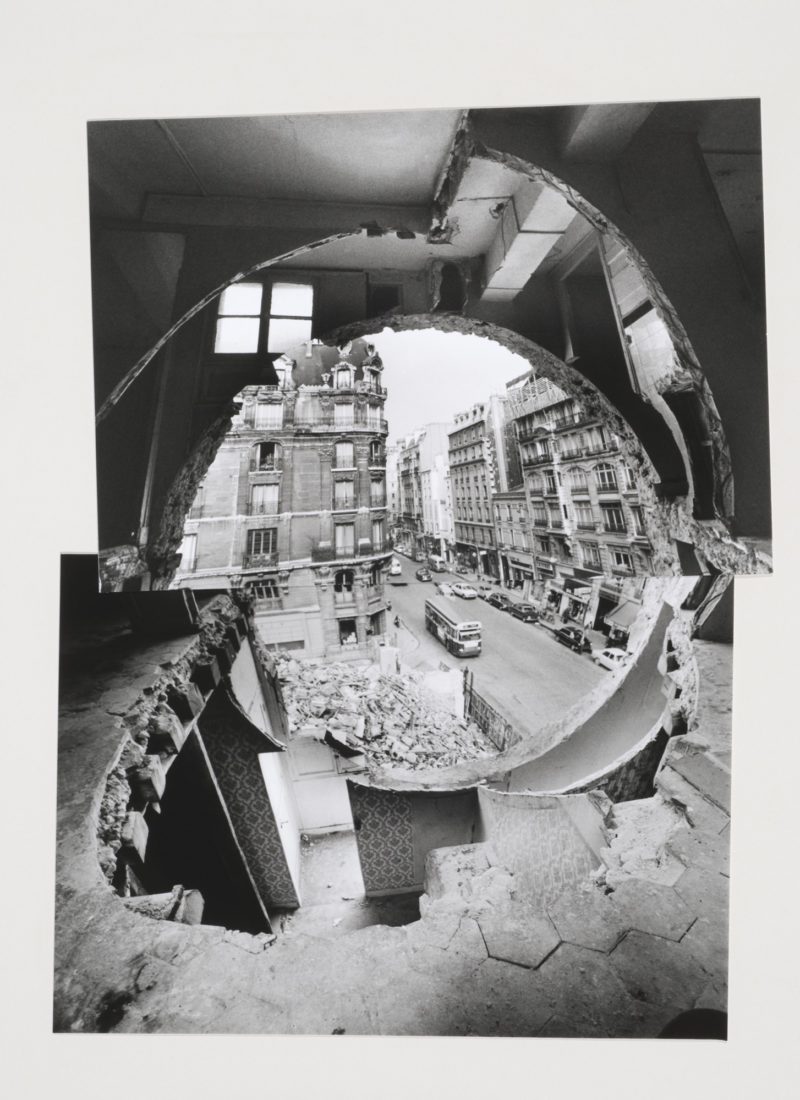

None of those interventions stood the test of time because the buildings were torn down. For that reason, drawings and pictures are the only witnesses of this strange architectural method, and therefore, his work has a strongly temporal nature. His photographs, however, are not only representatives of those interventions: Matta-Clark enlarged and cut up the color pictures and the Cibachrome. By reassembling them, he tried to suggest the spatial experience of his responses as pleasant as possible.

Why is his work still relevant?

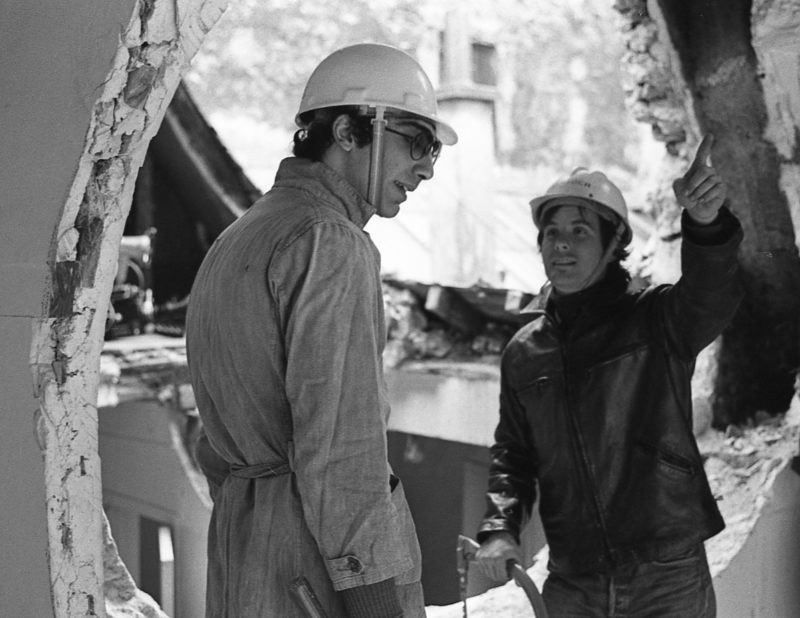

In the book Gordon Matta-Clark: Conical Intersect, the author Bruce Jenkins examines Matta-Clark’s proposals, working process, various sorts of documentation. He states that Matta-Clark’s decision to rework two abandoned buildings was an act of communication. The text is amid rarely seen photographs of the development process taken by French photographer Marc Petitjean.

Bruce Jenkins also states that Matta-Clark doesn’t have the name recognition of generations like Robert Smithson 5, whose work he superficially resembles, or Laurie Anderson, who was a neighborhood of an informal collective of downtown artists he brought together under the excellent of architecture.

Nonetheless, Jenkins suggests that Matta-Clark’s influence was critical — if not for the overall public, who remain mostly unaware of his large-scale 6, space-specific connections, then for other artists who share his experimentalism and his confidence in art as a collective power.

Conical Intersect

For Matta-Clark, Jenkins argues, this pair of meshing necessities came together most brightly in Conical Intersect, shaped for the ninth Biennale de Paris in 1975. The idea is simple but with implications, which could be said of all of Matta-Clark’s work.

A block away from the Centre Georges Pompidou, then below building, the artist digs two 17th century townhouses that had been planned for demolition, creating an enormous circular opening contracting from the surface towards the within of a building (from four meters to 2 meters) within the way of a spyglass.

The experimental and social aspects are apparent. Jenkins notes, the work aimed to debate what the Pompidou construction was doing to its neighborhood. At the same time, it offered a new way of watching and thinking about the two buildings which were about to be destroyed.

As Matta-Clark noted during a 1977 meeting:

The first thing one poster is that violence has been done. Then the fierceness turns into visual order and, hopefully, then to how of heightened awareness… You see that light enters places it else couldn’t. Angles and depths are often perceived where they need to are hidden. Spaces are available to maneuver through that were previously unreachable… I hope that the vitality of the action is frequently seen as an alternative vocabulary with which to inquiry the static, inert building atmosphere.

For his Paris project, Jenkins suggests, Matta-Clark was influenced by his desire to debate and his sense of reclamation as a source of flattening, of forgetting, during which the old (people, buildings, communities) are reliably uprooted or left behindhand. A native New Yorker, he had seen this in Manhattan 7 within the 1950s and 1960s, when influential city planner Robert Moses sought to remake the town in his image.

Video: Complete documentation of Conical Intersect

19 min 23 sec

Conclusion

Conclusion

Conical Intersect reveals the multivalent nature of the artist’s practice and his prescient specialization in sustainability and artistic reuse of the environment.

Matta-Clark’s influence on the Paris Biennale of 1975 manifested his critique of urban redevelopment within the type of a radical incision over two adjacent 17th-century buildings designated for demolition near the much-contested Centre Georges Pompidou, which was then under construction.

For this anti-monument, which poetically described the civic ruin, Matta-Clark bored a tornado-shaped hole that flew back at a 45-degree angle to exit through the roof. Periscopelike, the void offered onlookers a view of the structures’ internal skeletons.

Like in his interventions, the building itself constituted the work of art. To counter the fleeting nature of his sculptural gestures, he rivaled their dynamic spatial and time-based qualities in unique photographs made by splicing and grafting negatives to form quasi-Cubistic images. No substitute for complementary precariously on the flayed fringe of a basic cut, the pictures nevertheless document the essential aesthetic of Matta-Clark’s architecture.

Explore nearby

Les Halles, Paris

Etienne Lavie's billboard projectInstallation ended (dismantled in 2014)0 km away

Etienne Lavie's billboard projectInstallation ended (dismantled in 2014)0 km away Cy Twombly's Louvre ceiling1 km away

Cy Twombly's Louvre ceiling1 km away The Alberto Giacometti museum3 km away

The Alberto Giacometti museum3 km away Joan Miró's largest artworks3 km away

Joan Miró's largest artworks3 km away Lucio Fontana's neon installationsExhibition ended (dismantled in 2017)4 km away

Lucio Fontana's neon installationsExhibition ended (dismantled in 2017)4 km away