Who is artist Tehching Hsieh?

A bored painter turned performance artist, Tehching Hsieh is a Taiwanese born in Nan-Chou, Pinging Country, in 1950. Having tinkered with painting as his art medium, he became more interested in performance art and to catch his big break, he hitched a ride on an oil tanker in his 20s, arriving in Philadelphia.

From there, Hsieh moved to New York, where he was an undocumented immigrant worker taking on jobs such as dishwashing and cleaning. Then, in 1978, Hsieh embarked on what he has become incredibly renowned for – six performance art pieces performed over the next 22 years of his life. And thus, the performance artworks of this artist were born from his Tribeca apartment. Most of Hsieh’s performance art pieces have been to test endurance in a performative manner.

Artworks

Jump piece, 1973

Jump Piece is one of the legendary art pieces that Hsieh performed. While he performed this without prior knowledge of the art genre that was performance art, he took it as a test of endurance. Performed in 1973, Jump Piece is a series of photographs documenting Hsieh as he flung himself from a second-floor window to the concrete – a distance of about 15 feet – and upon landing, broke both of his ankles and shocked the entirety of his local community. As a result of Jump Piece, Hsieh recognized the need to build his artistic practice and felt the need to practice performance in a much less conservative atmosphere, thus setting his sights on New York.

Unable to get a visa, however, the artist trained as a sailor, joined the crew of an oil tanker and jumped ship upon docking in at a port in Philadelphia. Fortunately, though he lived and worked undocumented in New York for 14 years, he was granted amnesty in 1988. And in that period, as he adjusted to a new environment, worked and tried to explore his artistic practice, he succeeded in embarking on his durational performances – five 1-year performances and after, a 13-year plan all aimed at pushing the boundaries of performance arts.

Cage Piece (One Year Performance 1978–1979)

Following his intention to continue pushing the limits of performance art, Hsieh’s artwork was strictly disciplined and was governed by a contract certified by a lawyer. He started with Cage Piece. Performed between 1978 and 1979, Cage Piece is a performance art piece where the artist confined himself to a room akin to a cell rejecting all contact with the world save for a friend who delivered his food and clothes. He also received visitors in strict visiting hours who came to witness his performance every three weeks.

In this one year, Hsieh purposefully did not engage in any form of activity such as reading, writing, watching television or listening to the radio. As with Jump Piece, he had a series of photographs taken to act as documentation of his performance. These depict him sitting on the cot and staring at the ceiling. It was a performance that showed the reality of penal incarceration or, in some moments, religious seclusion.

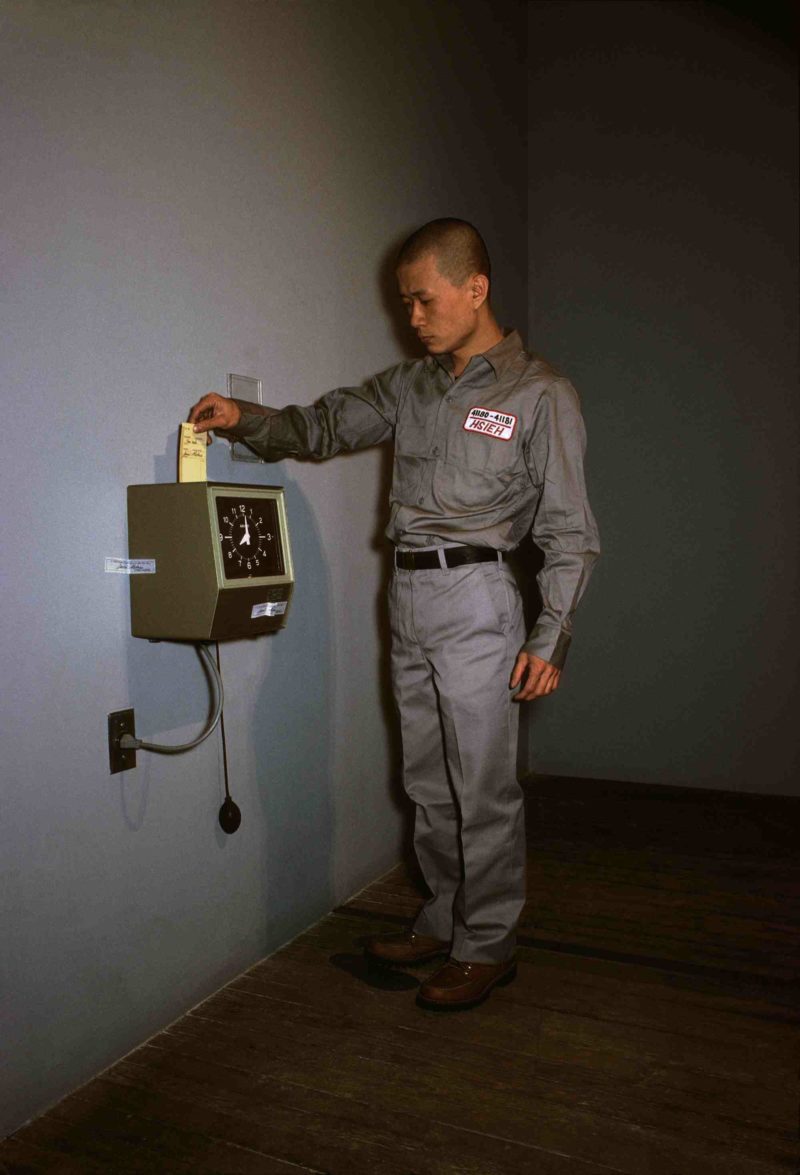

Time Clock Piece (One Year Performance 1980–1981)

After resting for a while upon the end of the performance of Cage Piece, Hsieh embarked on his second 1-year performance, Time Clock Piece, that lasted between 1980 and 1981.

During this performance, Hsieh started out with a shaved head and would punch on a factory clock every hour, taking a self-portrait each time. Due to the need to hit the timecard every hour, he subjected himself to a year without prolonged activity or sleep. Time Clock Piece explores the themes of monotonous industrial labor and the fatigue of a working-class life.

Outdoor Piece (One Year Performance 1981–1982)

This is Hsieh’s third performance artwork that started on September 26, 1981. The rule of this performance was to stay outdoors, never once going into a building, cat, ship, cave, tent, plane or subway, but to instead only have a sleeping bag. Thus began his year of being a voluntarily homeless man. Unfortunately, fate did not smile at him too kindly for that year. New York experienced one of the coldest winters of the century.

Hsieh got by through lighting fires, sleeping on cardboard sheets close to walls, as well as choosing other relatively sheltered places to sleep in, such as between parked cars to survive windy wintry nights.

During his year of living outdoors, Hsieh documented his experiences by writing notes about his food and where he slept. In addition, he would keep in touch with friends through occasional calls from public phones and to get the public to follow his performance. He would also occasionally put up posters that would inform them of where and when it would be possible for the public to meet with them.

Unfortunately, for Outdoor Piece, Hsieh was arrested for a fight and spent 15 hours at the police station. This art piece explores the vulnerability of humans exposed to urban elements without the comforts of shelter. While he did feel depressed upon resuming everyday life and reality, it begged the question of why he didn’t feel relieved instead. After all, could daily life be more dreary than the prospect of a whole year outdoors?

Rope Piece (Art/Life: One Year Performance 1983-1984 with Linda Montano)

The only one of Tehching Hsieh’s performances that involved another person, Rope Piece, was a performance that lasted between 1983 and 1984 where Hsieh tied himself to a fellow artist, Linda Montero, with an 8-foot long rope. This piece involved the pair spending every sleeping and waking moment of 365 days with a rule that they could not have any form of physical contact with each other in this duration.

To ensure that none would untie themselves without the knowledge of the public, they got two witnesses to seal the knots with lead and a year later, the two confirmed that the knots had not been tampered with. Also, Linda Montero and Tehching Hsieh did not know each other before the start of the performance.

The artwork explored the fact that it is possible to have proximity without intimacy, physical or psychological. While this piece did not have him pushing upon the boundaries of physical endurance, it was nevertheless a test of psychological endurance. It was a perspective on what is more restrictive, total isolation or proximity without intimacy?

No Art Piece (One Year Performance 1985–1986)

No Art Piece performed between 1985 and 1986 was based on the rule that Hsieh could not read, talk, see or do art and neither was he to visit any art galleries or museums. This piece, however, was difficult to document.

Thirteen Year Plan (Tehching Hsieh 1986–1999)

This performance counts as his sixth performance and his last one, after which he retired from artistic practice. This minimally documented performance lasted 13 years, officially starting on December 31, 1986, and ending on December 31, 1999.

It involved creating art privately without showing it to the public. This marked 13 years of his private artistic practice, after which when the new century, as well as a new millennium, dawned upon the world on January 1, 2000, Hsieh declared that he survived.

Asked why he took these breaks, such as in No Art Piece and for his Thirteen Year Plan to practice art privately, Hsieh emphasized that since an audience is secondary to an artist. He did make art for the audience, but also, to him, isolation gave him a chance to improve his artistic thinking and practice.

While his work required him to experience loneliness, isolation and discipline, isolating himself from society, privacy, art and autonomy, the artist still has refused to assign meaning to his work. Instead, Hsieh asserts that he is just passing time and doing so is neither important nor unimportant. Thus life and the very act of passing time, according to Hsieh, is paradoxical.

The Taiwanese Pavilion at Venice Biennale – Doing time

In 2000, Tehching Hsieh decided to stop making art and only archive and show previous art pieces. One of his most famous exhibitions happened in 2017 at the Venice Biennale and introduced his durational performance artworks to a whole new generation. Dubbed Doing Time, the exhibition shows an assembly of his documents, detailed installations and artifacts that use different documentation methods serving as an inquiry into what humans do when they are passing time. It is a discourse into the strength of discipline, will and endurance and how this affects human existence.

How do humans survive abject conditions?, his works seem to ask. How do those who have nothing or are restricted by circumstances find the will to survive? How do they pass their time here on earth? What role do physical endurance and psychological endurance have on the very existence of a human being?

While Hsieh refused to assign particular meaning to his work, it does not stop the viewer of his performance art pieces from making their own conjectures and drawing their own conclusion. But also, they shed light on Hsieh’s conditions at the time. Perhaps he had suffered throughout his period as an illegal immigrant trying to adjust to a whole new environment, which shows through his performances. Either way, does it all matter?

According to Hsieh, he is, after all, just passing time. The manner in which he chooses to do so does not matter in the very least. Doing Time thus, was a shocking insight into the radical performance arts. The final room of the exhibition showcased his previously unseen work, which included photographs and short performances that the artist had created while in Taipei. So profound was it that it became one of the most magnificent exhibitions of the 57th International Art Exhibition.

In particular, Doing Time at the Taiwan Pavilion presented Hsieh’s Outdoor Piece and Time Clock Piece and three of his unseen work. Videos show his pieces and photographs, notes, clothes, and other things he used to perform these works document these performances. Each of his recorded performances is accompanied by the statement of strict rules that he would define before embarking on the performance. The rules would govern, direct and restrict his behavior for the year and they often ensured endurance over physical difficulty and a complicated living process.

Analysis

As he said, his performances show different perspectives of thinking about life. For example, Time Clock Piece and Outdoor Piece depict deprivation and subjection to a system of control, while his pieces made before his emigration while in Taiwan are an expression of his departure from abstract painting and entry into performance art characterized by serial images, action and repetition.

Though Hsieh achieved recognition late, it was not due to the fact that his performance art pieces did not catch the eyes of New York’s art scene but rather because he was a Taiwanese artist barely speaking English and entry into the elitist New York Art Scene was incredibly difficult. In fact, Hsieh asserted that he still felt excluded and unable to assimilate into the contemporary art scene.

Besides, he was undocumented for 14 years. While he was ignored during his prime years of artistic practice, Tehching Hsieh is now a celebrated artist with the same institutions that did not exhibit his work, now scrambling to show his performances. The documentation of his performances is now proudly hanging at the Tate, MoMA and Guggenheim.

In a nutshell, he has stressed that his work is about human nature, the two sides of the coin that is freedom and discipline. Therefore, Hsieh created art that documented the living process and gave form to everyday life, physical struggles, and psychological pressures. All his performances, therefore, subscribe to time as it assigns meaning to human nature. This is a depiction of passing time, measuring this time, setting rules, restrictions and boundaries and being free or constrained by systems of control or being active or passive. Everything we do is passing time.

Therefore, it does not matter how one chooses to pass this time, but rather, human existence is an indication of this passage of time. Finally, Hsieh’s work is very relevant in today’s world, especially with the digital world and technological advances that have not only freed up our time but also created distractions. Thus, a walkthrough of this artist’s work poses a question for us to reflect upon how we spend the days and years of our lives.

Utopian Days – Freedom was an exhibition at the Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, South Korea’s first private art museum. Later it was shown in the same city at the Nowon Culture and Arts Center.

Artists: Adel Abdessemed, Lida Abdul, Phil America, Ivan Argote, Chim↑Pom, Minerva Cuevas, Chto Delat?, Cyprien Gaillard, Yang-Ah Ham, Andre Hemer, Tehching Hsieh, Zhang Huan, Jani Leinonen, Klara Liden, Armando Lulaj, Matt McCormick, Filippo Minelli, Wang Qingsong, Andres Serrano, Manit Sriwanichpoom, Clemens von Wedemeyer, Kacey Wong, Xijing Men, He Yunchang.

For many, Hsieh is a cult figure. The rigor and dedication of his art inspire passion, while the elusive and epic nature of his performances generates speculation and mythology. Since April 11, 1980, Tehching Hsieh hasn’t been able to sleep for a whole night without interruptions for twelve months.

To be precise, he hasn’t even been able to sleep for two hours running. Every 60 minutes, the sound signal produced by his watch connected to a loudspeaker woke him up and reminded him of the task he had self-imposed—that of clocking in at every single hour, 24 times a day, throughout a whole year.

Be it day or night, at every hour, Hsieh, wearing worker’s uniform, went to a grey-walled room in his loft in Manhattan and stamped a time card in a sign-in machine. A few seconds later, a 16 mm camera captured a picture of his tense face next to the machine.

A witness signed all the 366 time cards on the first day of the performance to assure that they couldn’t be replaced. Moreover, at the end of the twelve months, the witness confirmed that the 16 mm film was not falsified. Projected as a motion picture, it condenses a whole year into about six minutes.

The artist’s hair, which is shaved at the beginning of the film, reaches his shoulders at the end of it. To complete the film, Hsieh had to undergo extreme psychophysical stress and reorganize his own life meticulously around the passing of the hours; for instance, he could not move away from his loft for longer than 60 minutes.