Armando Lulaj, born in 1980 in Albania, is a writer of plays, texts on risk territory, film author, and producer of conflict images. He has no desire to be subject to the context of local belonging. Rather, he is orientated toward accentuating the border between economic power, fictional democracy and social disparity in a global context.

Exhibitions include the Prague Biennial (2003; 2007), Tirana Biennial (2005), the Albanian Pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennial (2007), 4th Gothenburg Biennale (2007), and the 6th Berlin Biennial (2010). His project NEVER was featured at the 63rd Berlinale International Film Festival in the section Forum Expanded.

Utopian Days – Freedom was an exhibition at the Total Museum of Contemporary Art, Seoul, South Korea’s first private art museum. Later, it was shown in the same city at the Nowon Culture and Arts Center.

Artists: Adel Abdessemed, Lida Abdul, Phil America, Ivan Argote, Chim↑Pom, Minerva Cuevas, Chto Delat?, Cyprien Gaillard, Yang-Ah Ham, Andre Hemer, Tehching Hsieh, Zhang Huan, Jani Leinonen, Klara Liden, Armando Lulaj, Matt McCormick, Filippo Minelli, Wang Qingsong, Andres Serrano, Manit Sriwanichpoom, Clemens von Wedemeyer, Kacey Wong, Xijing Men, He Yunchang.

Exhibited: Never, 2012

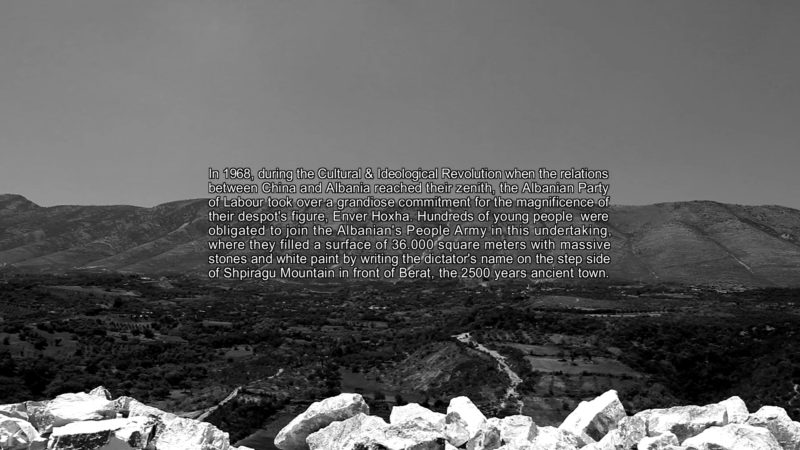

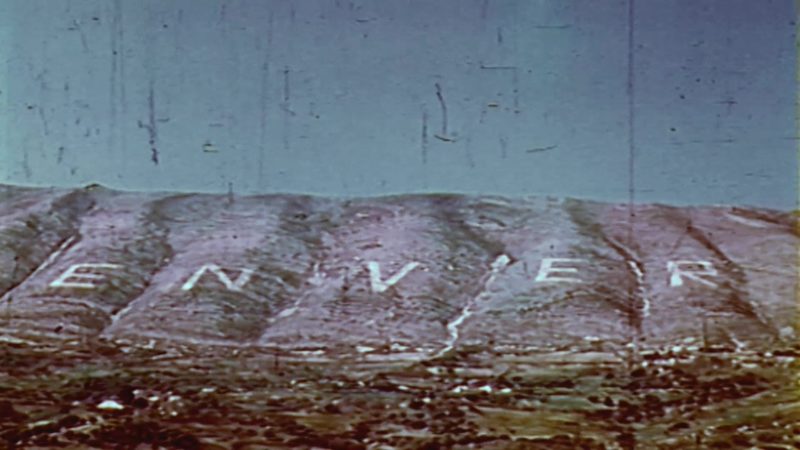

Until recently, one could still perceive the traces of a monumental inscription nearby the Albanian city of Berat: in the 1960s, former dictator Enver Hoxha1 had commissioned the sketching of his first name, Enver, onto the surrounding mountains.

With each letter measuring 150m in height, the gigantic ENVER2 remained visible even long after the end of the regime. After a failed attempt in the 1990s to eradicate the then nearly haunted inscription, the letters persisted – eventually giving rise to the project NEVER by Armando Lulaj.

In the summer of 2012, Lulaj succeeded in re-writing the dictator’s former commission, however, implementing a distinct alteration: ENVER became NEVER. In his documentary film of the same title, Lulaj offers a closer glimpse at his laborious re-dedication and the process of (un-) naming the recent past while, in a sense re-enacting the historical incident.

The NEVER-Chart, a diagram the artist developed to accompany the film, suggests further possible layers of meaning and intertwining discourses encompassing the work.

How corruption relates to déjà-vu photography, courage to cannibalism, or land art to Lacan, are only some of the aspects, which will form the basis of a comprehensive publication currently in development at the Jan Van Eyck Akademie.

excerpt

Courtesy of: DebatikCenter Film Production

Paolo Maria Deanesi Gallery

This interview has been edited for brevity and readability.

I started to work on the NEVER project in 2011 and to tell the truth, it was more than dealing with the past. It was dealing with the present. There are very interesting issues happening in Albania because art in Albania is considered more as a cartel, not coming from the art side or the art system, but from the political system. This is very important here.

When I was dealing with this project, I had to ask different institutions, of course, the government, the village, and the city in the front. These three institutions are the democratic party, the socialist party and the party which is in the middle. Iit was very difficult for me to get permission from these people. I worked for one year dealing with them and explaining my point of view in order to get this kind of permission, which in the end they didn’t give me because they wanted more than an artwork.

They wanted to use my project as an electoral tool and a way to earn money. So, I constructed the diagram that became the NEVER chart. With all my appointments with these people, this diagram is very conceptual and deals with issues of violence and corruption. So, I left out all these institutions and people from the government.

I went to the village and talked to the villagers to convince them. It was not easy because even the villagers see art as being more related to politics or a political party, which is not the case.

It was very difficult for me to explain my point of view, that art has nothing to do with a special political party but is political in itself. I explained my idea of NEVER turning the name of the dictator to NEVER. It was accepted by these people because some of them were working there in 1968, when ENVER, the name of the dictator, was written.

The letters are tall, something like 150 meters, and were made by the army itself using around 500 soldiers to construct the name with rocks taken from the nearby area. The young communists would paint those letters white at the end, and this happened every year as a kind of pilgrimage.

The young communists returned to the mountain and painted the letters white until the 1990s when the communist regime collapsed. Something happened in 1994 when the first Democratic Party wanted to destroy the name of the dictator. They sent the army there again and used dynamite to pulverize the rocks, but some failures occurred because the rocks were falling down, destroying the houses of the inhabitants.

So they abandoned this idea and used flamethrowers to burn the white surface of the rocks, but a disaster occurred: two soldiers burned alive. They died there, so they left this project until NATO covered it with bushes. Nothing was visible when I went there, but the inhabitants knew exactly where the letters started and ended, so we were able to construct the letters with the help of the villagers.

Around ten people worked there for over a month to construct the NEVER sign. It’s not simply a negation of the dictator’s name, ENVER. I think that the word NEVER puts at least symbolically challenges the condition of absolutism, which is disguised as democracy and which the choice of democracy excludes all possibilities. It is very interesting.

At that time, people from the city used to take photographs in front of the ENVER sign. Now, after the fall of the next regime, people from all over the world are taking pictures. You can see these pictures on blogs all over the world. They have been behind this NEVER sign, which is no longer a local situation but a global one that includes all of us.

NEVER is a Western word, and for me, it’s something that deals more with a global attitude, not anymore with a local one. Even Albania is somehow placed in a different interesting operation, like the covert operations held in Albania during the Cold War and things like that. Albania is a small country, but it has the potential to change the situation around the world a little bit.